Speciation

Learning

Allopatric Speciation: The Role of Isolation in Speciation!

The formation of two or more species often requires geographical isolation of subpopulations of the species. Only then can natural selection or perhaps genetic drift produce distinctive gene pools. It is no accident that the various subspecies of animals almost never occupy the same territory. Their distribution is allopatric (“other country”).

Darwin’s Finches

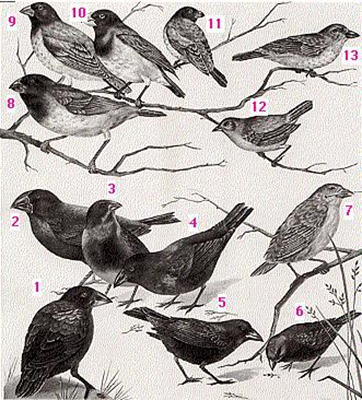

As a young man of 26, Charles Darwin visited the Galapagos Islands off the coast of Ecuador. Among the animals he studied were what appeared to be 13 species of finches found nowhere else on earth.

Some have stout beaks for eating seeds of one size or another (#2, #3, #6).

Others have beaks adapted for eating insects or nectar.

One (#7) has a beak like a woodpeckers. It uses it to drill holes in wood, but lacking the long tongue of a true woodpecker, it uses a cactus spine held in its beak to dig the insect out.

One (#12) looks more like a warbler than a finch, but its eggs, nest, and courtship behavior is like that of the other finches.

Darwin’s finches. The finches numbered 1–7 are ground finches. They seek their food on the ground or in low shrubs. Those numbered 8–13 are tree finches. They live primarily on insects.

- Large cactus finch (Geospiza conirostris)

- Large ground finch (Geospiza magnirostris)

- Medium ground finch (Geospiza fortis)

- Cactus finch (Geospiza scandens)

- Sharp-beaked ground finch (Geospiza difficilis)

- Small ground finch (Geospiza fuliginosa)

- Woodpecker finch (Cactospiza pallida)

- Vegetarian tree finch (Platyspiza crassirostris)

- Medium tree finch (Camarhynchus pauper)

- Large tree finch (Camarhynchus psittacula)

- Small tree finch (Camarhynchus parvulus)

- Warbler finch (Certhidia olivacea)

- Mangrove finch (Cactospiza heliobates)

(From BSCS, Biological Science: Molecules to Man, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1963)

Whether the number is 13 or 17, since Darwin’s time, these birds have provided a case study of how a single species reaching the Galapagos from Central or South America could – over a few million years – give rise to the various species that live there today. Several factors have been identified that may contribute to speciation.

Sympatric Speciation

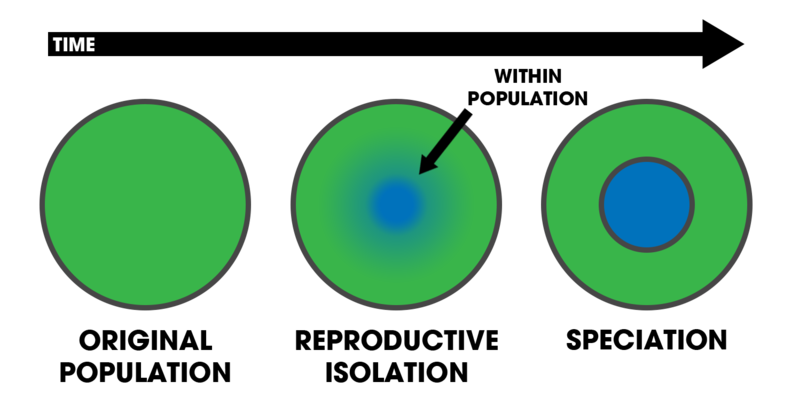

In contrast to Allopatric Speciation, Sympatric Speciation refers to the formation of two or more descendant species from a single ancestral species all occupying the SAME geographic location. Some evolutionary biologists do not believe that it can actually occur. They feel that interbreeding would soon eliminate any genetic differences that might appear. But there is some indirect evidence that sympatric speciation can occur, possibly arising from errors in chromosomes during cell division.

- Aneuploidy: Two few chromosomes

- Autopolyploidy: Two or more complete sets of chromosomes after division

- Allopolyploid: Gametes from two different species combine.

- Over time, mate selection could drive continued genetic divergence to establish reproductive barriers between these smaller sub-populations.

- Therefore, even though these groups may occupy the same locale, they will not be able to produce viable offspring if they interbreed, thus maintaining separation of the new species.

Summary

- Speciation is the process by which a single species can be split into multiple, different species.

- Individuals of the same species can evolve separately if they become isolated, either by place, time or circumstance.

- Speciation usually requires both a) Population Isolation and b) Genetic Divergence.

- There are (2) main ways in which the process of speciation can occur:

- Allopatric Speciation – a physical barrier develops to separate different groups.

- Sympatric Speciation – isolation occurs without geographic separation (controversial).

Sources:

Speciation. (2020, December 31). Retrieved May 26, 2021, from https://bio.libretexts.org/@go/page/5918

File:Sympatric Speciation Schematic.svg, Digital schematic of Sympatric Speciation. Aug 8, 2017. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International