Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

“Instead of creating a one-size-fits-all approach to teaching, consider implementing a teaching approach that provides flexible instructional methods, materials and assessments that can be tweaked to meet the needs of your diverse learning population. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) takes into consideration that we all learn differently and, therefore, should be provided with options for learning materials and for demonstrating learning.” [1]

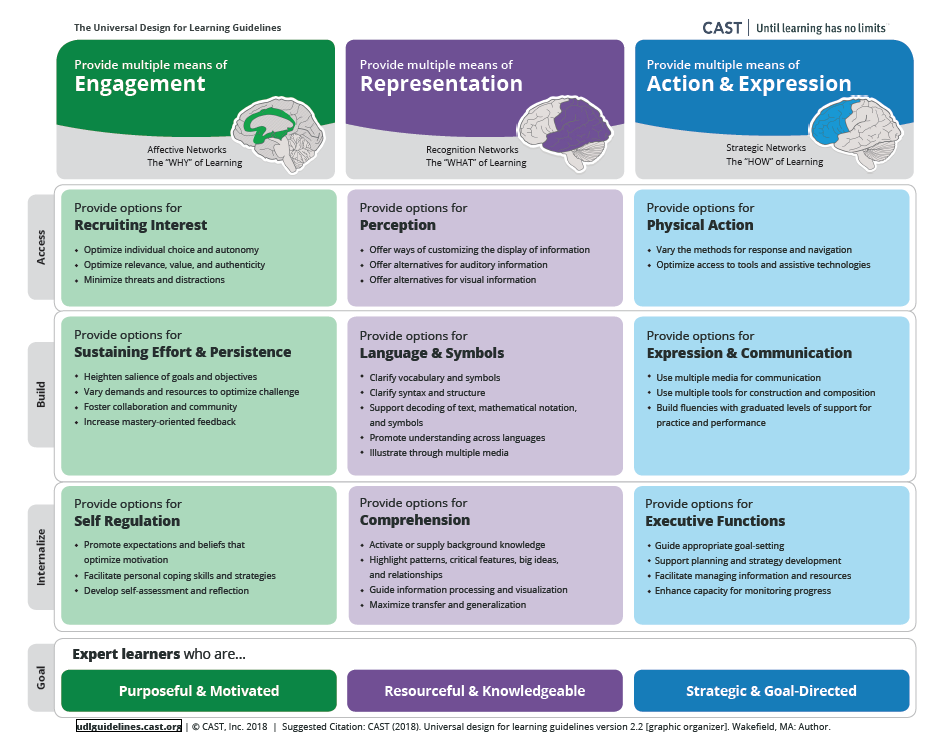

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a set of principles for curriculum development that is designed to meet individual learning needs. It “provides a blueprint for creating instructional goals, methods, materials, and assessments that work for everyone–not a single, one-size-fits-all solution but rather flexible approaches that can be customized and adjusted for individual needs” (CAST, 2016). The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST) is an organization that is internationally recognized as a leader in the field of UDL. They have developed a framework to improve and optimize teaching and learning for all people based on scientific insights into how humans learn. The framework is based on cognitive neuroscience and identifies three brain networks that are involved in learning. CAST not only identifies these three brain networks, but they have also developed principles and strategies to apply to each. Application of these principles and strategies will help meet the needs of diverse students. Visit their website for more information about the CAST organization and UDL.

The U.S. Congress (2008) also emphasized the importance of Universal Design for Learning when they defined UDL in the Higher Education Opportunity Act in 2008 as a scientifically valid framework that:

- Provides flexibility in the ways information is presented, in the ways students respond or demonstrate knowledge and skills, and in the ways students are engaged

- Reduces barriers in instruction

- Provides appropriate accommodations, supports, and challenges

- Maintains high achievement expectations for all students, including students with disabilities and students who are limited English proficient” (110th Congress, 2008, sec. 103, p. 122 stat. 3088)

As neuroscience has revealed that the way in which we learn is “as varied and unique as our DNA or fingerprints,” a one size fits all approach to teaching and learning may not meet the needs of our diverse learners (CAST, 2016). Whether faculty are teaching online or face-to-face, the application of the UDL Framework and principles will benefit all learners.

UDL in Practice

The UDL Guidelines are a tool used in the implementation of Universal Design for Learning. These guidelines offer a set of concrete suggestions that can be applied to any discipline or domain to ensure that all learners can access and participate in meaningful, challenging learning opportunities.

UDL can be viewed as a combination of addressing accessibility needs in a proactive way and giving all students a chance to internalize information and express themselves in a variety of formats.

UDL can be viewed as a combination of addressing accessibility needs in a proactive way and giving all students a chance to internalize information and express themselves in a variety of formats.

Example: Instead of providing a script to a video after a student requests an accommodation, providing it up front for the entire class could be beneficial to more than that one student. It also delays the process of a student having to reach out for specific requests.

Example: Adding alternative text to images, specifically more complex images like graphs and charts, provides a benefit to all learners that are trying to interpret it for themselves. This has historically been added for accessibility purposes, but students that do not specifically disclose a disability could have an easier time interpreting images with this added context.

When it comes to assignment submissions, you may think back to “alternative assignment types” for students that were unable to submit a specific assignment type. Opening up the possibility of flexible assignment types gives all learners an opportunity to explore what works best for them. Some students might opt for a written essay, while others may feel more comfortable creating a video of themselves talking about a topic. Giving students a chance to own their assignment submission type is a great way to give them ownership of demonstrating mastery of learning objectives.

The WHY of Learning (Engagement)

Affect represents a crucial element to learning, and learners differ markedly in the ways in which they can be engaged or motivated to learn. There are a variety of sources that can influence individual variation in affect including neurology, culture, personal relevance, subjectivity, and background knowledge, along with a variety of other factors. Some learners are highly engaged by spontaneity and novelty while others are disengaged, even frightened, by those aspects, preferring strict routine. Some learners might like to work alone, while others prefer to work with their peers. In reality, there is not one means of engagement that will be optimal for all learners in all contexts; providing multiple options for engagement is essential.

Examples:

- Include specific alignment criteria to the course or weekly learning outcomes. Be transparent of why this material is important and how it fits into the larger picture.

- Encourage (or require) students to state how goals will be achieved

- Give students a reflective assignment at the end of the course

- Incorporate a self-assessment activity

- Provide multiple avenues for absorbing content

The WHAT of Learning (Representation)

Learners differ in the ways that they perceive and comprehend information that is presented to them. For example, those with sensory disabilities (e.g., blindness or deafness); learning disabilities (e.g., dyslexia); language or cultural differences, and so forth may all require different ways of approaching content. Others may simply grasp information quicker or more efficiently through visual or auditory means rather than printed text. Also learning, and transfer of learning, occurs when multiple representations are used, because they allow students to make connections within, as well as between, concepts. In short, there is not one means of representation that will be optimal for all learners; providing options for representation is essential.

Examples:

- Provide descriptive alternative text for images and other visual content

- Caption videos or provide a script

- Provide a book on tape in parallel with a required reading

The HOW of Learning (Action and Expression)

Learners differ in the ways that they can navigate a learning environment and express what they know. For example, individuals with significant movement impairments (e.g., cerebral palsy), those who struggle with strategic and organizational abilities (executive function disorders), those who have language barriers, and so forth approach learning tasks very differently. Some may be able to express themselves well in written text but not speech, and vice versa. It should also be recognized that action and expression require a great deal of strategy, practice, and organization, and this is another area in which learners can differ. In reality, there is not one means of action and expression that will be optimal for all learners; providing options for action and expression is essential.

Examples:

- Direct students to review the rubric before submitting their assignments

- Provide students a choice in their submission type (video, audio response, written response)

- Create flexible rubrics to accommodate various submission types

- Word counts for written submissions, time minimums for videos, and number of slides for PowerPoints should be provided and equitable across submission types[2]

Additional Resources

Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST)

- CAST is the nonprofit that developed the UDL framework. They have the most relevant, up-to-date resources and serve as the standard for online course design. They offer information on research and development, applicable infographics, and free learning tools to use in your classroom. Click on the “Our Work” tab to see specifics on UDL resources they offer.

Teaching Online Preparation Toolkit (TOPkit) – CC BY-NC-SA

- TOPkit is a collaborative site used for educators across the globe. They have topics on course design, faculty development, accessibility, UDL, and many more. They encourage sharing of resources, such as sample courses, PDFs, presentation materials, and general advice through discussion threads.

- Universal Design for Learning (UDL). by TOPkit. Retrieved from https://topkit.org/developing/content-considerations/udl/ Licensed under: CC BY-NC-SA ↵

- Entire section adapted from Universal Design for Learning (UDL). by TOPkit. Retrieved from https://topkit.org/developing/content-considerations/udl/ Licensed under: CC BY-NC-SA ↵