Throughout American history, women have always played a vital role in economic production. The nature of women’s labor has changed and evolved over time. Prior to the industrial revolution, most labor took place at home. Men and women worked at home on family farms in the pre-industrial economy. Both men and women’s contributions to the family economy were crucial.

In the early nineteenth century, the economy of the United States was transformed by the rise of industry and the market revolution. In the new economy, both men and women increasingly worked outside of the home in factories to earn wages. While popular culture suggested that women should focus on domestic duties and not work for wages, this option was really only available for middle-to-upper class women. Poor women had to work in factories for wages to supplement the income of their family. In the new economy, many women faced competing pressures. Women were still expected to perform most domestic labor including child care; yet, they also increasingly needed to work for wages.

The Lowell Girl

The drive to produce cloth transformed the American system of labor. In the early republic, laborers in manufacturing might typically have been expected to work at every stage of production. But a new system, “piece work,” divided much of production into discrete steps performed by different workers. In this new system, merchants or investors sent or “put-out” materials to individuals and families to complete at home. These independent laborers then turned over the partially finished goods to the owner to be given to another laborer to finish.

As early as the 1790s, however, merchants in New England began experimenting with machines to replace the “putting-out” system. To effect this transition, merchants and factory owners relied on the theft of British technological knowledge to build the machines they needed. The fruits of American industrial espionage peaked in 1813 when Francis Cabot Lowell and Paul Moody recreated the powered loom used in the mills of Manchester, England. Lowell had spent two years in Britain observing and touring mills in England. He committed the design of the powered loom to memory so that, no matter how many times British customs officials searched his luggage, he could smuggle England’s industrial know-how into New England.

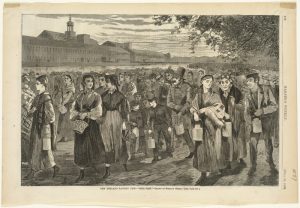

Lowell’s contribution to American industrialism was not only technological, it was organizational. He helped reorganize and centralize the American manufacturing process. A new approach, the Waltham-Lowell System, created the textile mill that defined antebellum New England and American industrialism before the Civil War. The modern American textile mill was fully realized in the planned mill town of Lowell in 1821, four years after Lowell himself died. Powered by the Merrimack River in northern Massachusetts and operated by local farm girls, the mills of Lowell centralized the process of textile manufacturing under one roof. The modern American factory was born. Soon ten thousand workers labored in Lowell alone. Sarah Rice, who worked at the nearby Millbury factory, found it “a noisy place” that was “more confined than I like to be.” Working conditions were harsh for the many desperate “mill girls” who operated the factories relentlessly from sun-up to sun-down. One worker complained that “a large class of females are, and have been, destined to a state of servitude.” Women workers went on strike. They lobbied for better working hours. But the lure of wages was too much. As another worker noted, “very many Ladies…have given up millinery, dressmaking & school keeping for work in the mill.” With a large supply of eager workers, Lowell’s vision brought a rush of capital and entrepreneurs into New England.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, families in the northern United States increasingly participated in the cash economy created by the market revolution. The first stirrings of industrialization shifted work away from the home. These changes transformed Americans’ notions of what constituted work, and therefore shifted what it meant to be an American woman. As Americans encountered more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the ability to remove women and children from work determined a family’s class status. This ideal, of course, ignored the reality of women’s work at home and was possible for only the wealthy. The market revolution therefore not only transformed the economy, it changed the nature of the American family. As the market revolution thrust workers into new systems of production, it redefined gender roles. The market integrated families into a new cash economy. As Americans purchased more goods in stores and produced fewer at home, the purity of the domestic sphere—the idealized realm of women and children—increasingly signified a family’s class status.

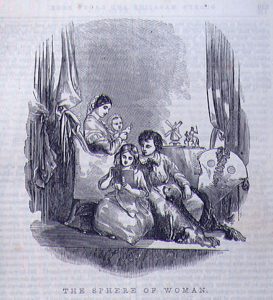

American culture expected men and women to assume distinct gender roles as they prepared for marriage and family life. An ideology of “separate spheres” set the public realm—the world of economic production and political life—apart as a male domain, and the world of consumers and domestic life as a female one. (Even non-working women labored by shopping for the household, producing food and clothing, cleaning, educating children, and performing similar activities. But these were considered “domestic” because they did not bring money into the household, although they too were essential to the household’s economic viability.) While reality muddied the ideal, the divide between a private, female world of home, and a public, male world of business defined American gender hierarchy.

The idea of separate spheres also displayed a distinct class bias. Middle- and upper-classes reinforced their status by shielding “their” women from the harsh realities of wage labor. Women were to be mothers and educators, not partners in production. But lower-class women continued to contribute directly to the household economy. The middle- and upper-class ideal was only feasible in households where women did not need to engage in paid labor. In poorer households, women engaged in wage labor as factory workers, piece-workers producing items for market consumption, tavern and inn keepers, and domestic servants. While many of the fundamental tasks women performed remained the same—producing clothing, cultivating vegetables, overseeing dairy production, and performing any number of other domestic labors—the key difference was whether and when they performed these tasks for cash in a market economy.

Domestic expectations constantly changed and the market revolution transformed many women’s traditional domestic tasks. Cloth production, for instance, advanced throughout the market revolution as new mechanized production increased the volume and variety of fabrics available to ordinary people. This relieved many better-off women of a traditional labor obligation. As cloth production became commercialized, women’s home-based cloth production became less important to household economies. Purchasing cloth, and later, ready-made clothes, began to transform women from producers to consumers. One woman from Maine, Martha Ballard, regularly referenced spinning, weaving, and knitting in the diary she kept from 1785 to 1812. Martha, her daughters, and female neighbors spun and plied linen and woolen yarns and used them to produce a variety of fabrics to make clothing for her family. The production of cloth and clothing was a year-round, labor-intensive process, but it was for home consumption, not commercial markets.

In cities, where women could buy cheap imported cloth to turn into clothing, they became skilled consumers. They stewarded money earned by their husbands by comparing values and haggling over prices.

Women might also parlay their feminine skills into businesses. In addition to working as seamstresses, milliners, or laundresses, women might undertake paid work for neighbors or acquaintances or combine clothing production with management of a boarding house. Even slaves with particular skill at producing clothing could be hired out for a higher price, or might even negotiate to work part-time for themselves. Most slaves, however, continued to produce domestic items, including simpler cloths and clothing, for home consumption.

Similar domestic expectations played out in the slave states. Enslaved women labored in the fields. Whites argued that African American women were less delicate and womanly than white women and therefore perfectly suited for agricultural labor. The southern ideal meanwhile established that white plantation mistresses were shielded from manual labor because of their very whiteness. Throughout the slave states, however, aside from the minority of plantations with dozens of slaves, the majority of white women by necessity continued to assist with planting, harvesting, and processing agricultural projects despite the cultural stigma attached to it. White southerners continued to produce large portions of their food and clothing at home. Even when they were market-oriented producers of cash crops, white southerners still insisted that their adherence to plantation slavery and racial hierarchy made them morally superior to greedy Northerners and their callous, cutthroat commerce. Southerners and northerners increasingly saw their ways of life as incompatible.

While the market revolution remade many women’s economic roles, their legal status remained essentially unchanged. Upon marriage, women were rendered legally dead by the notion of coverture, the custom that counted married couples as a single unit represented by the husband. Without special precautions or interventions, women could not earn their own money, own their own property, sue, or be sued. Any money earned or spent belonged by law to their husbands. Women shopped on their husbands’ credit and at any time husbands could terminate their wives’ access to their credit.

To be considered a success in family life, a middle-class American man typically aspired to own a comfortable home and to marry a woman of strong morals and religious conviction who would take responsibility for raising virtuous, well-behaved children. The duties of the middle-class husband and wife would be clearly delineated into separate spheres. The husband alone was responsible for creating wealth and engaging in the commerce and politics—the public sphere. The wife was responsible for the private—keeping a good home, being careful with household expenses, raising children, and inculcating them with the middle class virtues that would ensure their future success. But for poor families sacrificing the potential economic contributions of wives and children was an impossibility.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The Lowell Girl

Northern industrialization expanded rapidly following the War of 1812. Industrialized manufacturing began in New England, where wealthy merchants built water-powered textile mills (and mill towns to support them) along the rivers of the Northeast. These mills introduced new modes of production centralized within the confines of the mill itself. As never before, production relied on mechanized sources with water power, and later steam, to provide the force necessary to drive machines. In addition to the mechanization and centralization of work in the mills, specialized, repetitive tasks assigned to wage laborers replaced earlier modes of handicraft production done by artisans at home. The operations of these mills irrevocably changed the nature of work by deskilling tasks, breaking down the process of production to its most basic, elemental parts. In return for their labor, the workers, who at first were young women from rural New England farming families, received wages. From its origin in New England, manufacturing soon spread to other regions of the United States.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, merchants in the Northeast and elsewhere turned their attention as never before to the benefits of using unskilled wage labor to make a greater profit by reducing labor costs. They used the putting-out system, which the British had employed at the beginning of their own Industrial Revolution, whereby they hired farming families to perform specific tasks in the production process for a set wage. In the case of shoes, for instance, American merchants hired one group of workers to cut soles into standardized sizes. A different group of families cut pieces of leather for the uppers, while still another was employed to stitch the standardized parts together. This process proved attractive because it whittled production costs. The families who participated in the putting-out system were not skilled artisans. They had not spent years learning and perfecting their craft and did not have ambitious journeymen to pay. Therefore, they could not demand—and did not receive—high wages. Most of the year they tended fields and orchards, ate the food that they produced, and sold the surplus. Putting-out work proved a welcome source of extra income for New England farm families who saw their profits dwindle from new competition from midwestern farms with higher-yield lands.

Much of this part-time production was done under contract to merchants. Some farming families engaged in shoemaking (or shoe assemblage), as noted above. Many made brooms, plaited hats from straw or palm leaves, crafted furniture, made pottery, or wove baskets. Some, especially those who lived in Connecticut, made parts for clocks. The most common part-time occupation, however, was the manufacture of textiles. Farm women spun woolen thread and wove fabric. They also wove blankets, made rugs, and knit stockings. All this manufacturing took place on the farm, giving farmers and their wives control over the timing and pace of their labor. Their domestic productivity increased the quantity of goods available for sale in country towns and nearby cities.

President Jefferson’s embargo on British manufactured goods from late 1807 to early 1809 spurred more New England merchants to invest in industrial enterprises. By 1812, seventy-eight new textile mills had been built in rural New England towns. More than half turned out woolen goods, while the rest produced cotton cloth. Slater’s mills and those built in imitation of his were fairly small, employing only seventy people on average. Workers were organized the way that they had been in English factories, in family units. Under the “Rhode Island system,” families were hired. The father was placed in charge of the family unit, and he directed the labor of his wife and children. Instead of being paid in cash, the father was given “credit” equal to the extent of his family’s labor that could be redeemed in the form of rent (of company-owned housing) or goods from the company-owned store.

The Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 played a pivotal role in spurring industrial development in the United States. Jefferson’s embargo prevented American merchants from engaging in the Atlantic trade, severely cutting into their profits. The acute economic problems led some New England merchants, including Francis Cabot Lowell, to cast their gaze on manufacturing. Lowell had toured English mills during a stay in Great Britain. He returned to Massachusetts having memorized the designs for the advanced textile machines he had seen in his travels, especially the power loom, which replaced individual hand weavers. Lowell convinced other wealthy merchant families to invest in the creation of new mill towns. In 1813, Lowell and these wealthy investors, known as the Boston Associates, created the Boston Manufacturing Company. Together they raised $400,000 and, in 1814, established a textile mill in Waltham and a second one in the same town shortly thereafter.

At Waltham, cotton was carded and drawn into coarse strands of cotton fibers called rovings. The rovings were then spun into yarn, and the yarn woven into cotton cloth. Yarn no longer had to be put out to farm families for further processing. All the work was now performed at a central location—the factory. The work in Lowell’s mills was both mechanized and specialized. Specialization meant the work was broken down into specific tasks, and workers repeatedly did the one task assigned to them in the course of a day. As machines took over labor from humans and people increasingly found themselves confined to the same repetitive step, the process of deskilling began.

The Boston Associates’ mills, which each employed hundreds of workers, were located in company towns, where the factories and worker housing were owned by a single company. This gave the owners and their agents control over their workers. The most famous of these company towns was Lowell, Massachusetts. The new town was built on land the Boston Associates purchased in 1821 from the village of East Chelmsford at the falls of the Merrimack River, north of Boston. The mill buildings themselves were constructed of red brick with large windows to let in light. Company-owned boarding houses to shelter employees were constructed near the mills.

In contrast to many smaller mills, the Boston Associates’ enterprises avoided the Rhode Island system, preferring individual workers to families. These employees were not difficult to find. The competition New England farmers faced from farmers now settling in the West, and the growing scarcity of land in population-dense New England, had important implications for farmers’ children. Realizing their chances of inheriting a large farm or receiving a substantial dowry were remote, these teenagers sought other employment opportunities, often at the urging of their parents. While young men could work at a variety of occupations, young women had more limited options. The textile mills provided suitable employment for the daughters of Yankee farm families.

Needing to reassure anxious parents that their daughters’ virtue would be protected and hoping to avoid what they viewed as the problems of industrialization—filth and vice—the Boston Associates established strict rules governing the lives of these young workers. The women lived in company-owned boarding houses to which they paid a portion of their wages. They woke early at the sound of a bell and worked a twelve-hour day during which talking was forbidden. They could not swear or drink alcohol, and they were required to attend church on Sunday. Overseers at the mills and boarding-house keepers kept a close eye on the young women’s behavior; workers who associated with people of questionable reputation or acted in ways that called their virtue into question lost their jobs and were evicted.

The mechanization of formerly handcrafted goods, and the removal of production from the home to the factory, dramatically increased output of goods. For example, in one nine-month period, the numerous Rhode Island women who spun yarn into cloth on hand looms in their homes produced a total of thirty-four thousand yards of fabrics of different types. In 1855, the women working in just one of Lowell’s mechanized mills produced more than forty-three thousand yards. The Boston Associates’ cotton mills quickly gained a competitive edge over the smaller mills established by Samuel Slater and those who had imitated him. Their success prompted the Boston Associates to expand.

In Massachusetts, in addition to Lowell, they built new mill towns in Chicopee, Lawrence, and Holyoke. In New Hampshire, they built them in Manchester, Dover, and Nashua. And in Maine, they built a large mill in Saco on the Saco River. Other entrepreneurs copied them. By the time of the Civil War, 878 textile factories had been built in New England. All together, these factories employed more than 100,000 people and produced more than 940 million yards of cloth.

Alongside the production of cotton and woolen cloth, which formed the backbone of the Industrial Revolution in the United States as in Britain, other crafts increasingly became mechanized and centralized in factories in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Summary

Before the industrial revolution, most work took place at home. Men typically performed agricultural labor on the farm. Meanwhile, women performed domestic labor and produced goods such as clothing at home for their families consumption. Both men and women were seen as contributing to the family economy in the pre-industrial era.

The industrial revolution and the rise of a market-based economy radically changed the nature of work. Work was increasingly defined as labor that took place outside of the home in return for wages. With the coming of the industrial revolution, clothing was produced in factories by wage laborers. Most of the employees in the textile factories were young women. Poor women worked in the factories out of necessity to supplement the income of their families.

An ideology of separate spheres emerged to reshape gender norms. Women faced pressure to focus on domestic duties such as caring for their children, while men faced pressure to earn money in the paid labor force. In reality, the domestic “ideal” was available only to middle-to-upper class women, who did not need to earn wages in the paid labor force. Poor women and enslaved women had to work outside of the domestic sphere out of necessity.