The industrial revolution began in Great Britain in the mid-eighteenth century. By the late-eighteenth century, industrial manufacturing began to emerge in the United States. Industry flourished in New England and Mid-Atlantic states. The rise of industry created a new working class. This new working class included men, women and children. The new working class faced long hours, low wages, and dangerous conditions in factories. In response, American workers began to form trade unions and labor unions to promote their interests. With the rise of industry, inequality and class divisions became more prominent in the United States. The old artisan system of production became increasingly marginalized and antiquated as a new industrial nation emerged.

Creating the Working Class

While industrialization bypassed most of the American South, southern cotton production nevertheless nurtured industrialization in the Northeast and Midwest. The drive to produce cloth transformed the American system of labor. In the early republic, laborers in manufacturing might typically have been expected to work at every stage of production. But a new system, “piece work,” divided much of production into discrete steps performed by different workers. In this new system, merchants or investors sent or “put-out” materials to individuals and families to complete at home. These independent laborers then turned over the partially finished goods to the owner to be given to another laborer to finish.

As early as the 1790s, however, merchants in New England began experimenting with machines to replace the “putting-out” system. To effect this transition, merchants and factory owners relied on the theft of British technological knowledge to build the machines they needed. In 1789, for instance, a textile mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island contracted twenty-one-year-old British immigrant Samuel Slater to build a yarn-spinning machine and then a carding machine. Slater had apprenticed in an English mill and succeeded in mimicking the English machinery. The fruits of American industrial espionage peaked in 1813 when Francis Cabot Lowell and Paul Moody recreated the powered loom used in the mills of Manchester, England. Lowell had spent two years in Britain observing and touring mills in England. He committed the design of the powered loom to memory so that, no matter how many times British customs officials searched his luggage, he could smuggle England’s industrial know-how into New England.

Lowell’s contribution to American industrialism was not only technological, it was organizational. He helped reorganize and centralize the American manufacturing process. A new approach, the Waltham-Lowell System, created the textile mill that defined antebellum New England and American industrialism before the Civil War. The modern American textile mill was fully realized in the planned mill town of Lowell in 1821, four years after Lowell himself died. Powered by the Merrimack River in northern Massachusetts and operated by local farm girls, the mills of Lowell centralized the process of textile manufacturing under one roof. The modern American factory was born. Soon ten thousand workers labored in Lowell alone.

The market revolution shook other industries as well. Craftsmen began to understand that new markets increased the demand for their products. Some shoemakers, for instance, abandoned the traditional method of producing custom-built shoes at their home workshop and instead began producing larger quantities of shoes in ready-made sizes to be shipped to urban centers.

Manufacturers wanting increased production abandoned the old personal approach of relying upon a single live-in apprentice for labor and instead hired unskilled wage laborers who did not have to be trained in all aspects of making shoes but could simply be assigned a single repeatable aspect of the task. Factories slowly replaced shops. The old paternalistic apprentice system, which involved long-term obligations between apprentice and master, gave way to a more impersonal and more flexible labor system in which unskilled laborers could be hired and fired as the market dictated. A writer in the New York Observer in 1826 complained, “The master no longer lives among his apprentices [and] watches over their moral as well as mechanical improvement.” Masters-turned-employers now not only had fewer obligations to their workers, they had a lesser attachment. They no longer shared the bonds of their trade but were subsumed under a new class-based relationships: employers and employees, bosses and workers, capitalists and laborers. On the other hand, workers were freed from the long-term, paternalistic obligations of apprenticeship or the legal subjugation of indentured servitude. They could theoretically work when and where they wanted. When men or women made an agreement with an employer to work for wages, they were “left free to apportion among themselves their respective shares, untrammeled…by unwise laws,” as Reverend Alonzo Potter rosily proclaimed in 1840. But while the new labor system was celebrated throughout the northern United States as “free labor,” it was simultaneously lamented by a growing powerless class of laborers.

As the northern United States rushed headlong toward commercialization and an early capitalist economy, many Americans grew uneasy with the growing gap between wealthy businessmen and impoverished wage laborers. Elites like Daniel Webster might defend their wealth and privilege by insisting that all workers could achieve “a career of usefulness and enterprise” if they were “industrious and sober,” but labor activist Seth Luther countered that capitalism created “a cruel system of extraction on the bodies and minds of the producing classes…for no other object than to enable the ‘rich’ to ‘take care of themselves’ while the poor must work or starve.”

Americans embarked upon their industrial revolution with the expectation that all men could start their careers as humble wage workers but later achieve positions of ownership and stability with hard work. Wage work had traditionally been looked-down upon as a state of dependence, suitable only as a temporary waypoint for young men without resources on their path toward the middle class and the economic success necessary to support a wife and children ensconced within the domestic sphere. Children’s magazines – such as Juvenile Miscellany and Parley’s Magazine – glorified the prospect of moving up the economic ladder. This “free labor ideology” provided many Northerners with a keen sense of superiority over the slave economy of the southern states.

But the commercial economy often failed in its promise of social mobility. Depressions and downturns might destroy businesses and reduce owners to wage work. Even in times of prosperity unskilled workers might perpetually lack good wages and economic security and therefore had to forever depend upon supplemental income from their wives and young children.

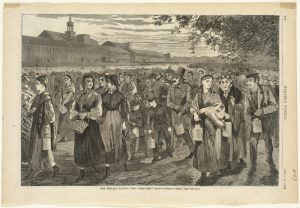

Wage workers—a population disproportionately composed of immigrants and poorer Americans—faced low wages, long hours, and dangerous working conditions. Class conflict developed. Instead of the formal inequality of a master-servant contract, employer and employee entered a contract presumably as equals. But hierarchy was evident: employers had financial security and political power; employees faced uncertainty and powerlessness in the workplace. Dependent upon the whims of their employers, some workers turned to strikes and unions to pool their resources. In 1825 a group of journeymen in Boston formed a Carpenters’ Union to protest their inability “to maintain a family at the present time, with the wages which are now usually given.” Working men organized unions to assert themselves and win both the respect and the resources due to a breadwinner and a citizen.

For the middle-class managers and civic leaders caught between workers and owners, unions enflamed a dangerous antagonism between employers and employees. They countered any claims of inherent class conflict with the ideology of social mobility. Middle-class owners and managers justified their economic privilege as the natural product of superior character traits, including decision-making and hard work. One group of master carpenters denounced their striking journeyman in 1825 with the claim that workers of “industrious and temperate habits, have, in their turn, become thriving and respectable Masters, and the great body of our Mechanics have been enabled to acquire property and respectability, with a just weight and influence in society.” In an 1856 speech in Kalamazoo, Michigan, Abraham Lincoln had to assure his audience that the country’s commercial transformation had not reduced American laborers to slavery. Southerners, he said “insist that their slaves are far better off than Northern freemen. What a mistaken view do these men have of Northern labourers! They think that men are always to remain labourers here – but there is no such class. The man who laboured for another last year, this year labours for himself. And next year he will hire others to labour for him.” It was this essential belief that undergirded the northern commitment to “free labor” and won the market revolution much widespread acceptance.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

Creating the Working Class

The profound economic changes sweeping the United States led to equally important social and cultural transformations. The formation of distinct classes, especially in the rapidly industrializing North, was one of the most striking developments. The unequal distribution of newly created wealth spurred new divisions along class lines.

The Economic Elite

Economic elites gained further social and political ascendance in the United States due to a fast-growing economy that enhanced their wealth and allowed distinctive social and cultural characteristics to develop among different economic groups. In the major northern cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, leading merchants formed an industrial capitalist elite. Many came from families that had been deeply engaged in colonial trade in tea, sugar, pepper, slaves, and other commodities and that were familiar with trade networks connecting the United States with Europe, the West Indies, and the Far East. These colonial merchants had passed their wealth to their children.

After the War of 1812, the new generation of merchants expanded their economic activities. They began to specialize in specific types of industry, spearheading the development of industrial capitalism based on factories they owned and on specific commercial services such as banking, insurance, and shipping. Junius Spencer Morgan, for example, rose to prominence as a banker. His success began in Boston, where he worked in the import business in the 1830s. He then formed a partnership with a London banker, George Peabody, and created Peabody, Morgan & Co. In 1864, he renamed the enterprise J. S. Morgan & Co. His son, J. P. Morgan, became a noted financier in the later nineteenth and early twentieth century.

Members of the northern business elite forged close ties with each other to protect and expand their economic interests. Marriages between leading families formed a crucial strategy to advance economic advantage, and the homes of the northern elite became important venues for solidifying social bonds. Exclusive neighborhoods started to develop as the wealthy distanced themselves from the poorer urban residents, and cities soon became segregated by class.

Industrial elites created chambers of commerce to advance their interests; by 1858 there were ten in the United States. These networking organizations allowed top bankers and merchants to stay current on the economic activities of their peers and further strengthen the bonds among themselves. The elite also established social clubs to forge and maintain ties. The first of these, the Philadelphia Club, came into being in 1834. Similar clubs soon formed in other cities and hosted a range of social activities designed to further bind together the leading economic families. Many northern elites worked hard to ensure the transmission of their inherited wealth from one generation to the next. Politically, they exercised considerable power in local and state elections.

The Industrial Revolution led some former artisans to reinvent themselves as manufacturers. These enterprising leaders of manufacturing differed from the established commercial elite in the North and South because they did not inherit wealth. Instead, many came from very humble working-class origins and embodied the dream of achieving upward social mobility through hard work and discipline. As the beneficiaries of the economic transformations sweeping the republic, these newly established manufacturers formed a new economic elite that thrived in the cities and cultivated its own distinct sensibilities. They created a culture that celebrated hard work, a position that put them at odds with southern planter elites who prized leisure and with other elite northerners who had largely inherited their wealth and status.

Peter Cooper provides one example of the new northern manufacturing class. Ever inventive, Cooper dabbled in many different moneymaking enterprises before gaining success in the glue business. He opened his Manhattan glue factory in the 1820s and was soon using his profits to expand into a host of other activities, including iron production. One of his innovations was the steam locomotive, which he invented in 1827. Despite becoming one of the wealthiest men in New York City, Cooper lived simply. Rather than buying an ornate bed, for example, he built his own. He believed respectability came through hard work, not family pedigree.

Peter Cooper, who would go on to found the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City, designed and built the Tom Thumb, the first American-built steam locomotive. Those who had inherited their wealth derided self-made men like Cooper, and he and others like him were excluded from the social clubs established by the merchant and financial elite of New York City. Selfmade northern manufacturers, however, created their own organizations that aimed to promote upward mobility. The Providence Association of Mechanics and Manufacturers was formed in 1789 and promoted both industrial arts and education as a pathway to economic success. In 1859, Peter Cooper established the Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art, a school in New York City dedicated to providing education in technology. Merit, not wealth, mattered most according to Cooper, and admission to the school was based solely on ability; race, sex, and family connections had no place. The best and brightest could attend Cooper Union tuition-free, a policy that remained in place until 2014.

The Middle Class

Not all enterprising artisans were so successful that they could rise to the level of the elite. However, many artisans and small merchants, who owned small factories and stores, did manage to achieve and maintain respectability in an emerging middle class. Lacking the protection of great wealth, members of the middle class agonized over the fear that they might slip into the ranks of wage laborers; thus they strove to maintain or improve their middle-class status and that of their children.

To this end, the middle class valued cleanliness, discipline, morality, hard work, education, and good manners. Hard work and education enabled them to rise in life. Middle-class children, therefore, did not work in factories. Instead they attended school and in their free time engaged in “self-improving” activities, such as reading or playing the piano, or they played with toys and games that would teach them the skills and values they needed to succeed in life. In the early nineteenth century, members of the middle class began to limit the number of children they had. Children no longer contributed economically to the household, and raising them “correctly” required money and attention. It therefore made sense to have fewer of them.

Middle-class women did not work for wages. Their job was to care for the children and to keep the house in a state of order and cleanliness, often with the help of a servant. They also performed the important tasks of cultivating good manners among their children and their husbands and of purchasing consumer goods; both activities proclaimed to neighbors and prospective business partners that their families were educated, cultured, and financially successful.

This class of upwardly mobile citizens promoted temperance, or abstinence from alcohol. They also gave their support to Protestant ministers like George Grandison Finney, who preached that all people possessed free moral agency, meaning they could change their lives and bring about their own salvation, a message that resonated with members of the middle class, who already believed their worldly efforts had led to their economic success.

The Working Class

The Industrial Revolution in the United States created a new class of wage workers, and this working class also developed its own culture. They formed their own neighborhoods, living away from the oversight of bosses and managers. While industrialization and the market revolution brought some improvements to the lives of the working class, these sweeping changes did not benefit laborers as much as they did the middle class and the elites. The working class continued to live an often precarious existence. They suffered greatly during economic slumps, such as the Panic of 1819.

Although most working-class men sought to emulate the middle class by keeping their wives and children out of the work force, their economic situation often necessitated that others besides the male head of the family contribute to its support. Thus, working-class children might attend school for a few years or learn to read and write at Sunday school, but education was sacrificed when income was needed, and many working-class children went to work in factories. While the wives of wage laborers usually did not work for wages outside the home, many took in laundry or did piecework at home to supplement the family’s income.

Although the urban working class could not afford the consumer goods that the middle class could, its members did exercise a great deal of influence over popular culture. Theirs was a festive public culture of release and escape from the drudgery of factory work, catered to by the likes of Phineas Taylor Barnum, the celebrated circus promoter and showman. Taverns also served an important function as places to forget the long hours and uncertain wages of the factories. Alcohol consumption was high among the working class, although many workers did take part in the temperance movement. It is little wonder that middle-class manufacturers attempted to abolish alcohol.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Summary

In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, industry flourished in the north. Businessmen in the north embraced industrial technology from Britain. With the rise of manufacturing in the north, the old artisan system of apprenticeship became increasingly marginalized. A new class of wage workers emerged to labor in factories. In the textile mills of Lowell, Massachusetts, most of these laborers were wormen. The working conditions in the factory faced long hours, low wages, and dangerous working conditions. Workers responded to these conditions by organizing labor unions to fight for higher wages and shorter hours.