In the nation’s first few years, no organized political parties existed. This began to change as U.S. citizens argued bitterly about the proper size and scope of the new national government.

As a result, the 1790s witnessed the rise of opposing political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans. Federalists saw unchecked democracy as a dire threat to the republic, and they pointed to the excesses of the French Revolution as proof of what awaited. Democratic-Republicans opposed the Federalists’ notion that only the wellborn and well educated were able to oversee the republic; they saw it as a pathway to oppression by an aristocracy.

In June 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the federal Constitution, and the new plan for a strong central government went into effect. Elections for the first U.S. Congress were held in 1788 and 1789, and members took their seats in March 1789. In a reflection of the trust placed in him as the personification of republican virtue, George Washington became the first president in April 1789. John Adams served as his vice president.

Political divisions quickly became apparent. Washington and Adams represented the Federalist Party, which generated a backlash among those who resisted the new government’s assertions of federal power.

The First Party System

Supporters of the 1787 federal constitution, known as Federalists, adhered to a decidedly British notion of social hierarchy. The Federalists did not, at first, compose a political party. Instead, Federalists held certain shared assumptions. For them, political participation continued to be linked to property rights, which barred many citizens from voting or holding office.

The architects of the Constitution held a majority among the members of the new national government. Many assumed the new executive posts the first Congress created. Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton, a leading Federalist, as secretary of the treasury.

Alexander Hamilton’s Program

Alexander Hamilton, Washington’s secretary of the treasury, was an ardent nationalist who believed a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills. In the early 1790s, he created the foundation for the U.S. financial system.

For the national government to be effective, Hamilton deemed it essential to have the support of those to whom it owed money. In January 1790, he recommended that the new federal government honor all its debts, including all paper money issued by the Confederation and the states during the war, at face value. To pay these debts, Hamilton proposed that the federal government sell bonds to the public. These bonds would have the backing of the government and yield interest payments. Creditors could exchange their old notes for the new government bonds.

Hamilton’s plan to convert notes to bonds immediately generated controversy about the size and scope of the government. Some saw the plan as an unjust use of federal power, while Hamilton argue that Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution granted the government “implied powers” that gave the green light to his program.

As secretary of the treasury, Hamilton hoped to stabilize the American economy further by establishing a national bank. Hamilton’s bank proposal generated opposition. Jefferson argued that the Constitution did not permit the creation of a national bank. In response, Hamilton again invoked the Constitution’s implied powers. President Washington backed Hamilton’s position and signed legislation creating the bank in 1791.

The Democratic-Republican Party and the First Party System

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson felt the federal government had overstepped its authority by adopting the treasury secretary’s plan.

Jefferson also took issue with what he perceived as favoritism given to commercial classes in the principal American cities. He thought urban life widened the gap between the wealthy few and an underclass of landless poor workers who, because of their oppressed condition, could never be good republican property owners. Rural areas, in contrast, offered far more opportunities for property ownership and virtue. Jefferson believed that self-sufficient, property-owning republican citizens or yeoman farmers held the key to the success and longevity of the American republic.

Opposition to Hamilton began in earnest in the early 1790s. Jefferson turned to his friend Philip Freneau to help organize the effort through the publication of the National Gazette as a counter to the Federalist press, especially the Gazette of the United States. From 1791 until 1793, Freneau’s partisan paper attacked Hamilton’s program and Washington’s administration.

Newspapers did not aim to be objective; instead, they served to broadcast the views of a particular party. The Gazette of the United States featured articles from leading Federalists like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. The National Gazette was founded two years later to counter their political influence.

Opposition to the Federalists led to the formation of Democratic-Republican societies, composed of men who felt the domestic policies of the Washington administration were designed to enrich the few. Democratic-Republicans championed limited government. Their fear of centralized power originated in the experience of the 1760s and 1770s when the British Parliament attempted to impose its will on the colonies. The 1787 federal constitution, written in secret by fifty-five wealthy men of property and standing, ignited fears of a similar menacing plot. To opponents, the Federalists promoted aristocracy.

While wealthy merchants and planters formed the core of the Federalist leadership, members of the Democratic-Republican societies came from the ranks of artisans. These citizens saw themselves as acting in the spirit of 1776. Their efforts against the Federalists were a battle to preserve republicanism, to promote the public good against private self-interest. They published their views, held meetings to voice their opposition, and sponsored festivals and parades.

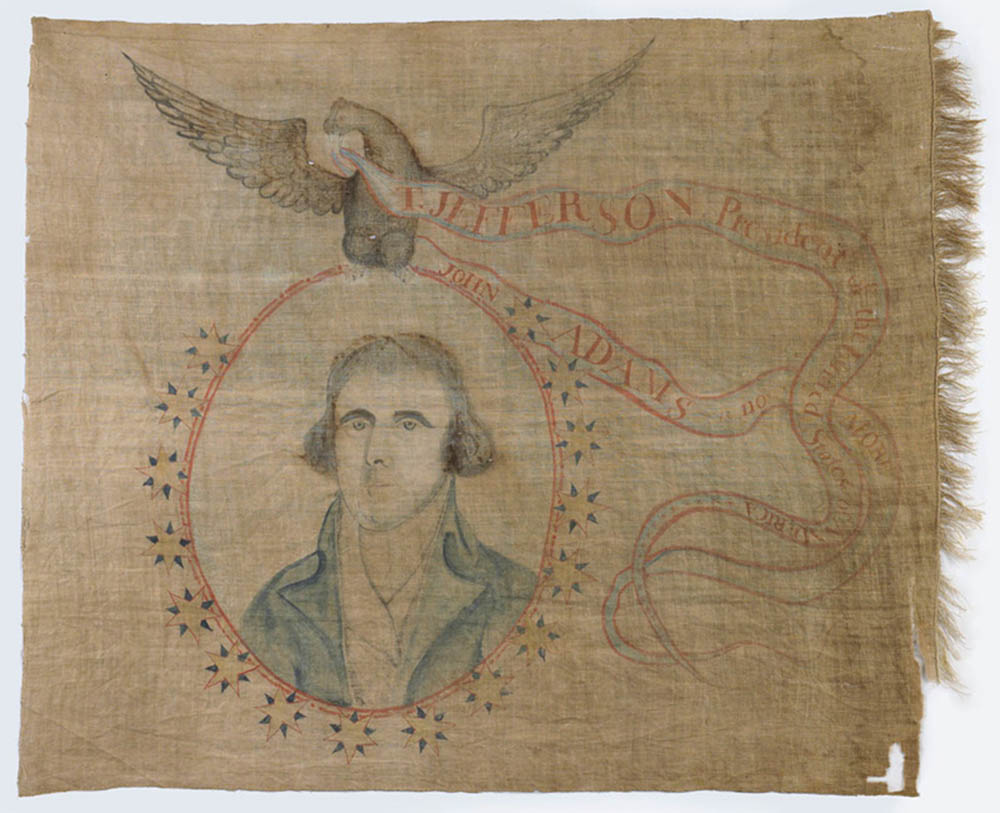

George Washington, who had been reelected in 1792, refused to run for a third term. In the presidential election of 1796, the two parties—Federalist and Democratic-Republican—competed for the first time. Federalist John Adams defeated his Democratic-Republican rival Thomas Jefferson by a narrow margin. In 1800, another close election swung the other way, and Jefferson began a long period of Democratic-Republican government.

The Presidency of John Adams

The war between Great Britain and France in the 1790s shaped U.S. foreign policy. As a new and extremely weak nation, the American republic had no control over European events, and no real leverage to obtain its goals of trading freely in the Atlantic. To Federalist president John Adams, relations with France posed the biggest problem.

Because France and Great Britain were at war, the French issued decrees stating that any ship carrying British goods could be seized. In practice, this meant the French would target American ships. As a result, France and the United States waged an undeclared war from 1796 to 1800. The French seized 834 American ships. This outraged the American public and turned public opinion against France. In the court of public opinion, Federalists appeared to have been correct in their interpretation of France, while the pro-French Democratic-Republicans had been misled.

The Alien and Sedition Acts

The surge of animosity against France led Congress to pass several measures that in time undermined Federalist power. The Alien and Sedition Acts aimed to increase national security against what most had come to regard as the French menace. The Sedition Act imposed harsh penalties on those convicted of speaking or writing “in a scandalous or malicious” manner against the government of the United States. Twenty-five men, all Democratic-Republicans, were indicted under the act, and ten were convicted.

The Alien and Sedition Acts raised constitutional questions about the freedom of the press provided under the First Amendment. Democratic-Republicans argued that the acts were evidence of the Federalists’ intent to squash individual liberties and, by enlarging the powers of the national government, crush states’ rights. Jefferson and Madison mobilized the response to the acts in the form of statements known as the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, which argued that the acts were illegal and unconstitutional.

The Revolution of 1800 and the Presidency of Thomas Jefferson

The Revolution of 1800 refers to the first transfer of power from one party to another in American history, when the presidency passed to Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson in the 1800 election.

The election did prove even more divisive than the 1796 election, however, as both the Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties waged a mudslinging campaign unlike any seen before. The Democratic-Republicans gained political ground. Jefferson viewed participatory democracy as a positive force for the republic, a direct departure from Federalist views. While Federalist statesmen, like the architects of the 1787 federal constitution, feared a pure democracy, Jefferson was far more optimistic that the common American farmer could be trusted to make good decisions.

Jefferson reversed the policies of the Federalist Party by turning away from urban commercial development. Instead, he promoted agriculture through the sale of western public lands in small and affordable lots. Perhaps Jefferson’s most lasting legacy is his vision of an “empire of liberty.” He distrusted cities and instead envisioned a rural republic of land-owning white men, or yeoman republican farmers. He wanted the United States to be the breadbasket of the world, exporting its agricultural commodities without suffering the ills of urbanization and industrialization. Jefferson championed the rights of states and insisted on limited federal government as well as limited taxes.

The slow decline of the Federalists, which began under Jefferson, led to a period of one-party rule in national politics. Though Federalists continued to enjoy popularity, especially in the Northeast, their days of prominence in setting foreign and domestic policy had ended.

Partisan Acrimony

The earliest years of the nineteenth century were hardly free of problems between the two political parties. Early in Jefferson’s term, controversy swirled over President Adams’s judicial appointments of many Federalists during his final days in office. When Jefferson took the oath of office, he refused to have the commissions for these Federalist justices delivered to the appointed officials.

The animosity between the political parties exploded into open violence in 1804, when Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s first vice president, and Alexander Hamilton engaged in a duel. When Democratic-Republican Burr lost his bid for the office of governor of New York, he was quick to blame Hamilton, who had long hated him and had done everything in his power to discredit him. On July 11, the two antagonists met in Weehawken, New Jersey, to exchange bullets in a duel in which Burr shot and mortally wounded Hamilton.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

The First Party System – videos

EMS History. The Rise of Political Parties. (2012, January 12). [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7AC9LjmJb_4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rQdBvpVTqyc

The Audiopedia. What is the First Party System. [Video file.] (2017, January 23). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rQdBvpVTqyc

Summary

From the very beginning of the American Republic, there have been major disputes among our nation’s political leaders. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, fundamental disputes resulted in the formation of two political parties. One political party was the Federalists. George Washington, John Adams, and Alexander Hamilton were the most prominent members of the Federalist Party. The Federalists supported a strong central government and the creation of a national bank. The Federalists envisioned the nation becoming a strong industrial power. The Federalists opposed democracy and believed that the elite should hold political power. The Federalists supported the British in their conflict with France. The Democratic Republicans arose in opposition to the Federalists. Thomas Jefferson was the most prominent member of the Democratic Republican Party. Jefferson believed that the central government had become too powerful. He wanted power to rest with the state governments. Jefferson celebrated the agrarian heritage of the nation. Jefferson believed that all white males, regardless of their wealth, should be able to play a role in the political process. Poor farmers generally supported the Democratic-Republicans.