Elite republican revolutionaries did not envision a completely new society; traditional ideas of gender norms, order and decorum remained firmly entrenched among members of their privileged class. Many Americans rejected the elitist and aristocratic republican order, however, and advocated radical changes. Their efforts represented a groundswell of sentiment for greater equality, a part of the democratic impulse unleashed by the Revolution.

Strict gender norms were entrenched in early American society. Under both custom and law, women were not regarded as fully independent beings. Under the principle of coverture, women were treated as a legal appendage of their fathers or husbands. The American Revolution sparked new thinking about the role and status of women in society. A number of women began to question the oppressive gender norms that were entrenched in American society, custom, and law.

The Republican Mother

In eighteenth-century America, as in Great Britain, the legal status of married women was defined as coverture, meaning a married woman had no legal or economic status independent of her husband. She could not conduct business or buy and sell property. Her husband controlled any property she brought to the marriage, although he could not sell it without her agreement. Married women’s status did not change as a result of the Revolution, and wives remained economically dependent on their husbands. The women of the newly independent nation did not call for the right to vote, but some, especially the wives of elite republican statesmen, began to agitate for equality under the law between husbands and wives, and for the same educational opportunities as men.

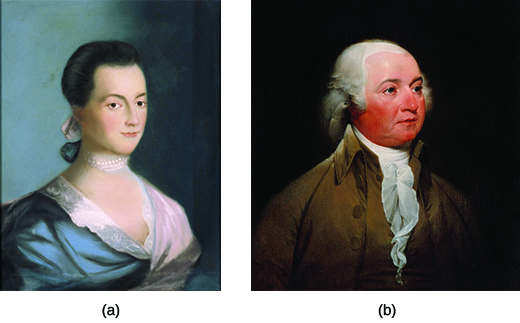

Some women hoped to overturn coverture. From her home in Braintree, Massachusetts, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, Whig leader John Adams, in 1776, “In the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestor. Do not put such unlimited power in the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.” Abigail Adams ran the family homestead during the Revolution, but she did not have the ability to conduct business without her husband’s consent. Elsewhere in the famous 1776 letter quoted above, she speaks of the difficulties of running the homestead when her husband is away. Her frustration grew when her husband responded in an April 1776 letter: “As to your extraordinary Code of Laws, I cannot but laugh. We have been told that our Struggle has loosened the bands of Government everywhere. That Children and Apprentices were disobedient—that schools and Colleges were grown turbulent—that Indians slighted their Guardians and Negroes grew insolent to their Masters. But your Letter was the first Intimation that another Tribe more numerous and powerful than all the rest were grown discontented. . . . Depend on it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”

Another privileged member of the revolutionary generation, Mercy Otis Warren, also challenged gender assumptions and traditions during the revolutionary era. Born in Massachusetts, Warren actively opposed British reform measures before the outbreak of fighting in 1775 by publishing anti-British works. In 1812, she published a three-volume history of the Revolution, a project she had started in the late 1770s. By publishing her work, Warren stepped out of the female sphere and into the otherwise male-dominated sphere of public life.

Inspired by the Revolution, Judith Sargent Murray of Massachusetts advocated women’s economic independence and equal educational opportunities for men and women. Murray, who came from a well-to-do family in Gloucester, questioned why boys were given access to education as a birthright while girls had very limited educational opportunities. She began to publish her ideas about educational equality beginning in the 1780s, arguing that God had made the minds of women and men equal.

Murray’s more radical ideas championed woman’s economic independence. She argued that a woman’s education should be extensive enough to allow her to maintain herself—and her family—if there was no male breadwinner. Indeed, Murray was able to make money of her own from her publications. Her ideas were both radical and traditional, however: Murray also believed that women were much better at raising children and maintaining the morality and virtue of the family than men.

Adams, Murray, and Warren all came from privileged backgrounds. All three were fully literate, while many women in the American republic were not. Their literacy and station allowed them to push for new roles for women in the atmosphere of unique possibility created by the Revolution and its promise of change. Female authors who published their work provide evidence of how women in the era of the American Revolution challenged traditional gender roles.

Overall, the Revolution reconfigured women’s roles by undermining the traditional expectations of wives and mothers, including subservience. In the home, the separate domestic sphere assigned to women, women were expected to practice republican virtues, especially frugality and simplicity. Republican motherhood meant that women, more than men, were responsible for raising good children, instilling in them all the virtue necessary to ensure the survival of the republic. The Revolution also opened new doors to educational opportunities for women. Men understood that the republic needed women to play a substantial role in upholding republicanism and ensuring the survival of the new nation. Benjamin Rush, a Whig educator and physician from Philadelphia, strongly advocated for the education of girls and young women as part of the larger effort to ensure that republican virtue and republican motherhood would endure.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

The Republican Mother

EMS History. The Cult of Domesticity, The Treatment of Women in the 19th Century, (2012, April 26). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sUZis01JaQo&t=317s

Summary

Women faced tremendous inequality in early American history. Women could not legally own property. Women did not receive the same educational opportunities as men. Women did not even have any legal custodial rights over their children, who were defined as the property of their father.

Women did not passively accept inequality. A number of women advocated for equal rights. Abigail Adams appealed to her husband John Adams to recognize women’s rights in the laws of the new nation. Women were regarded as morally superior to men in early American history. Women were regarded as the moral guardians of the family. Women were thought to be responsible for inculcating their children with Republican virtues and values.