Throughout the 19th century, the United States engaged in sporadic warfare with Native Americans. Territory often lay at the heart of these conflicts, although they were also informed by mutual misunderstandings, the distinctions between Native American and American ways of life, and the American government’s reservation policies. Historians analyzing this history have debated whether the government’s policies towards Native Americans represented a policy of genocide or a policy of forced assimilation.

Genocide vs. Forced Assimilation

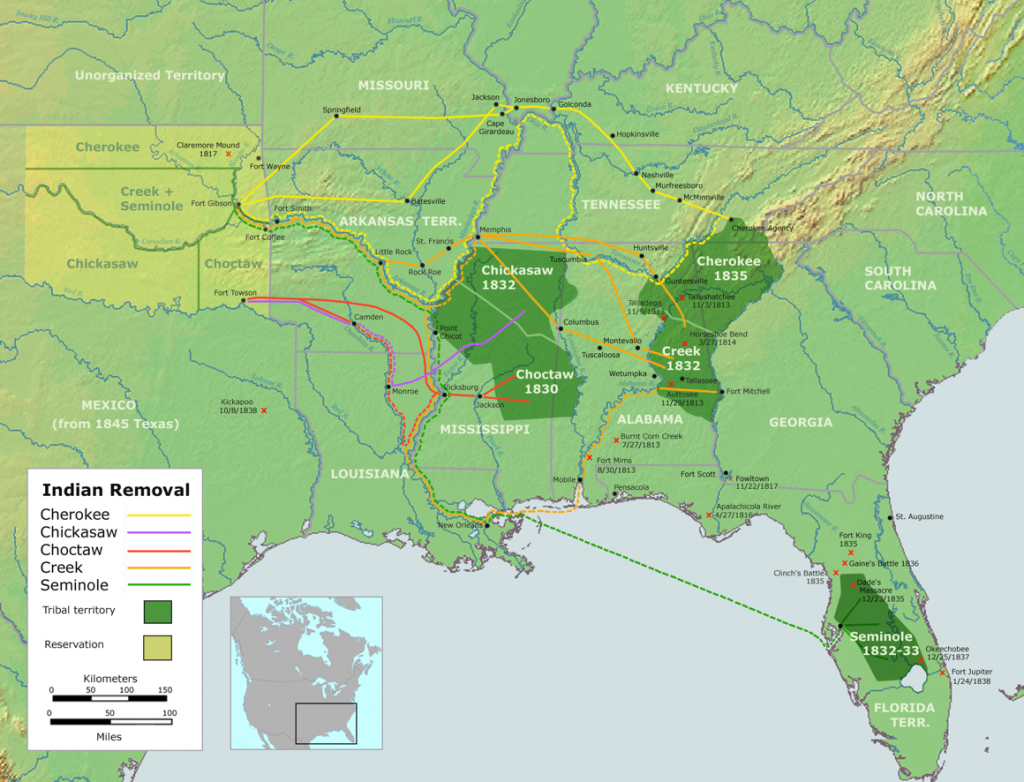

In the early 19th century, the United States adopted an official policy of “Indian Removal” in response to conflicts between American settlers and Native Americans in the southeast. Above all, the United States government was compelled to establish a policy of removal in order to expand the country’s territory. American action in Florida highlighted this policy in its formative years, as the American government seized Indians’ eastern lands, reduced lands available for runaway slaves, and killed entirely or removed Indian peoples farther west. This became the template for future action. Presidents, since at least Thomas Jefferson, had long discussed removal, but President Andrew Jackson took the most dramatic action. Jackson believed, “It [speedy removal] will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.” Desires to remove American Indians from valuable farmland motivated state and federal governments to cease trying to assimilate Indians and instead plan for forced removal.

Congress passed the Indian Removal Act in 1830, thereby granting the president authority to begin treaty negotiations that would give American Indians land in the West in exchange for their lands east of the Mississippi. Many advocates of removal, including President Jackson, rationalized the policy by paternalistically claiming they were “savages” and that removal would protect Indian communities from outside influences that jeopardized their chances of becoming “civilized” farmers. Jackson emphasized this paternalism—the belief that the government was acting in the best interest of Native peoples— in his 1830 State of the Union Address. “It [removal] will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of whites…and perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

The experience of the Cherokee was particularly brutal. Despite many tribal members adopting some Euro-American ways, including intensified agriculture, slave ownership, and Christianity; state and federal governments pressured the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations to sign treaties and surrender land. Many of these tribal nations used the law in hopes of protecting their lands. Most notable among these efforts was the Cherokee Nation’s attempt to sue the state of Georgia. Jackson wanted a solution that might preserve peace and his reputation. He sent Secretary of War Lewis Cass to offer title to western lands and the promise of tribal governance in exchange for relinquishing of the Cherokee’s eastern lands. These negotiations opened a rift within the Cherokee nation. Cherokee leader John Ridge believed removal was inevitable and pushed for a treaty that would give the best terms. Others, called nationalists and led by John Ross, refused to consider removal in negotiations. The Jackson administration refused any deal that fell short of large-scale removal of the Cherokee from Georgia, thereby fueling a devastating and violent intra-tribal battle between the two factions. Eventually tensions grew to the point that several treaty advocates were assassinated by members of the national faction.

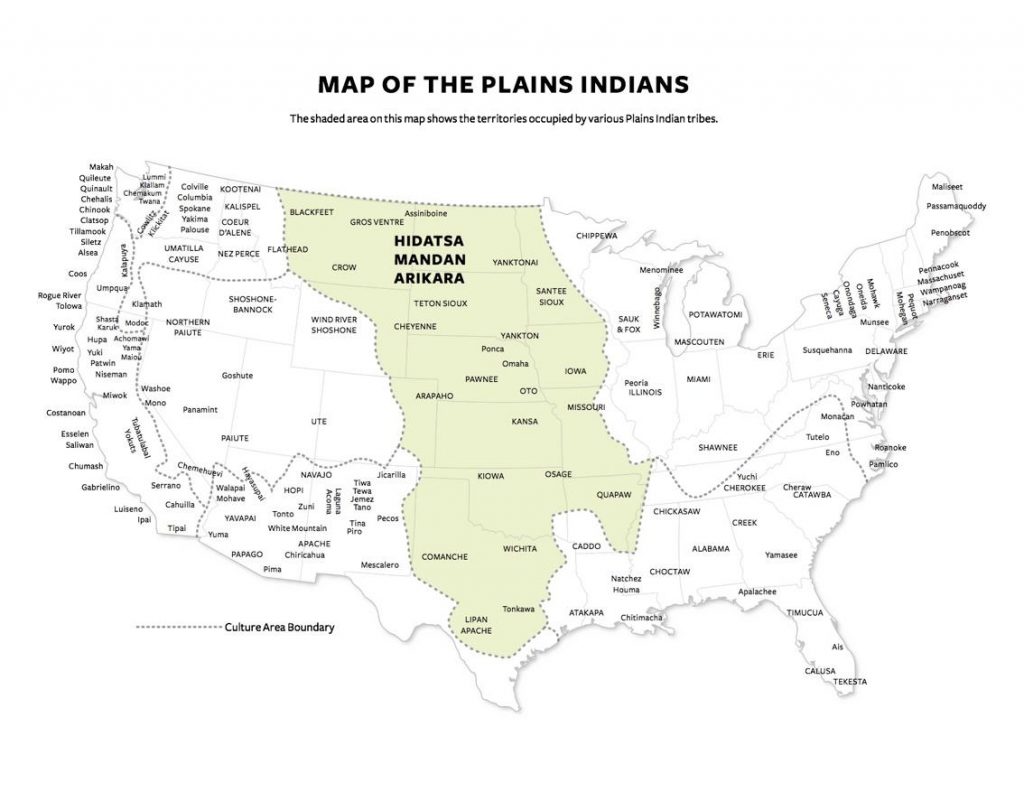

Despite the disaster of removal, tribal nations slowly rebuilt their cultures and in some cases even achieved prosperity in Indian Territory. Tribal nations blended traditional cultural practices, including common land systems, with western practices including constitutional governments, common school systems, and creating an elite slaveholding class. Some Indian groups remained too powerful to remove. Beginning in the late eighteenth-century, the Comanche rose to power in the Southern Plains region of what is now the southwestern United States. By quickly adapting to the horse culture first introduced by the Spanish, the Comanche transitioned from a foraging economy into a mixed hunting and pastoral society. After 1821, the new Mexican nation-state claimed the region as part of the Northern Mexican frontier, but they had little control. Instead, the Comanche remained in power and controlled the economy of the Southern Plains. A flexible political structure allowed the Comanche to dominate other Indian groups as well as Mexican and American settlers.

In the 1830s, the Comanche launched raids into northern Mexico, ending what had been an unprofitable but peaceful diplomatic relationship with Mexico. At the same time, they forged new trading relationships with Anglo-American traders in Texas. Throughout this period, the Comanche and several other independent Native groups, particularly the Kiowa, Apache, and Navajo engaged in thousands of violent encounters with Northern Mexicans. Collectively, these encounters comprised an ongoing war during the 1830s and 1840s as tribal nations vied for power and wealth. By the 1840s, Comanche power peaked with an empire that controlled a vast territory in the trans-Mississippi west known as Comancheria. By trading in Texas and raiding in Northern Mexico, the Comanche controlled the flow of commodities, including captives, livestock, and trade goods. They practiced a fluid system of captivity and captive trading, rather than a rigid chattel system. The Comanche used captives for economic exploitation but also adopted captives into kinship networks. This allowed for the assimilation of diverse peoples in the region into the empire. The U.S.-Mexican War, beginning in 1846, can be seen as a culmination of this violence.

In the Great Basin region, Mexican Independence also escalated patterns of violence. This region, on the periphery of the Spanish empire, was nonetheless integrated in the vast commercial trading network of the West. Mexican officials and Anglo-American traders entered the region with their own imperial designs. New forms of violence spread into the homelands of the Paiute and Western Shoshone. Traders, settlers, and Mormon religious refugees, aided by U.S. officials and soldiers, committed daily acts of violence and laid the groundwork for violent conquest. This expansion of the American state into the Great Basin meant groups such as the Ute, Cheyenne and Arapahoe had to compete over land, resources, captives, and trade relations with Anglo-Americans. Eventually, white incursion and ongoing Indian Wars resulted in traumatic dispossession of land and the struggle for subsistence.

The federal government attempted more than relocation of Americans Indians. Policies to “civilize” Indians coexisted along with forced removal and served an important “Americanizing” vision of expansion that brought an ever-increasing population under the American flag and sought to balance aggression with the uplift of paternal care. Thomas L. McKenney, superintendent of Indian trade from 1816 to 1822 and the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830, served as the main architect of the “civilization policy.” He asserted that American Indians were morally and intellectually equal to whites. He sought to establish a national Indian school system.

Congress rejected McKenney’s plan but instead passed the Civilization Fund Act in 1819. This act offered a $10,000 annual annuity to be allocated towards societies that funded missionaries to establish schools among Indian tribes. However, providing schooling for American Indians under the auspices of the Civilization program also allowed the federal government to justify taking more land. Treaties, such as the 1820 Treaty of Doak’s Stand made with the Choctaw nation, often included land cessions as requirements for education provisions. Removal and Americanization reinforced Americans sense of cultural dominance.

After removal in the 1830s, the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw began to collaborate with missionaries to build school systems of their own. Leaders hoped education would help ensuing generations to protect political sovereignty. In 1841, the Cherokee Nation opened a public school system that within two years included eighteen schools. By 1852, the system expanded to twenty-one schools with a national enrollment of 1,100 pupils. Many of the students educated in these tribally controlled schools later served their nations as teachers, lawyers, physicians, bureaucrats, and politicians.

President Martin van Buren, in 1838, decided to press the issue beyond negotiation and court rulings and used the New Echota Treaty provisions to order the army to forcibly remove those Cherokee not obeying the Treaty’s cession of territory. Sixteen thousand Cherokee began the journey, but harsh weather, poor planning, and difficult travel resulted in an estimated 10,138 deaths on what became known as the Trail of Tears. Not every instance was as treacherous as the Cherokee example and some tribes resisted removal. But over 60,000 Indians were forced west by the opening of the Civil War. Over time, as the American government repeatedly ignored earlier treaties with Native Americans, many Native American nations began to lose faith in the negotiation process with United States officials, and treaties were dubbed “bad paper.” Distrust would only further exacerbate Native American and U.S. relations.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Genocide vs. Forced Assimilation- Video

Genocide vs. Forced Assimilation

Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, “The ‘Indian Problem’,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=if-BOZgWZPE, 3 March 2015

Summary

Over the course of the 19th century, the United States government adopted an official policy of “Indian Removal,” which was officially instituted by Congress in 1830. Native American nations across North America would eventually feel the brunt of these policies, and they would lead to warfare, the forcible removal of Native Americans ancestral homelands, and recurring attempts to assimilate Native Americans into American society. Personally, how do you interpret this history? Was the United States government engaging in a policy of genocide or forced assimilation?