Prior to 1815, in the years before the market and Industrial Revolution, most Americans lived on farms where they produced much of the foods and goods they used. This largely pre-capitalist culture centered on large family units whose members all lived in the same towns, counties, and parishes.

Economic forces unleashed after 1815, however, forever altered that world. More and more people now bought their food and goods in the thriving market economy, a shift that opened the door to a new way of life. These economic transformations generated various reactions; some people were nostalgic for what they viewed as simpler, earlier times, whereas others were willing to try new ways of living and working. In the early nineteenth century, experimental communities sprang up, created by men and women who hoped not just to create a better way of life but to recast American civilization, so that greater equality and harmony would prevail. Indeed, some of these reformers envisioned the creation of alternative ways of living, where people could attain perfection in human relations. The exact number of these societies is unknown because many of them were so short-lived, but the movement reached its apex in the 1840s.

Utopian Communities

Most of those attracted to utopian communities had been profoundly influenced by evangelical Protestantism, especially the Second Great Awakening. However, their experience of revivalism had left them wanting to further reform society. The communities they formed and joined adhered to various socialist ideas and were considered radical, because members wanted to create a new social order, not reform the old.

German Protestant migrants formed several pietistic societies: communities that stressed transformative individual religious experience or piety over religious rituals and formality. One of the earliest of these, the Ephrata Cloister in Pennsylvania, was founded by a charismatic leader named Conrad Beissel in the 1730s. By the antebellum era, it was the oldest communal experiment in the United States. Its members devoted themselves to spiritual contemplation and a disciplined work regime while they awaited the millennium. They wore homespun rather than buying cloth or premade clothing, and encouraged celibacy. Although the Ephrata Cloister remained small, it served as an early example of the type of community that antebellum reformers hoped to create.

In 1805, a second German religious society, led by George Rapp, took root in Pennsylvania with several hundred members called Rappites who encouraged celibacy and adhered to the socialist principle of holding all goods in common. They not only built the town of Harmony but also produced surplus goods to sell to the outside world. In 1815, the group sold its Pennsylvanian holdings and moved to Indiana, establishing New Harmony on a plot along the Wabash River. In 1825, members returned to Pennsylvania, and established themselves in the town called Economy.

The Oneida Community

Another religious utopian experiment, the Oneida Community, began with the teachings of John Humphrey Noyes, a Vermonter who had graduated from Dartmouth, Andover Theological Seminary, and Yale. The Second Great Awakening exerted a powerful effect on him, and he came to believe in perfectionism, the idea that it is possible to be perfect and free of sin. Noyes claimed to have achieved this state of perfection in 1834.

Noyes applied his idea of perfection to relationships between men and women, earning notoriety for his unorthodox views on marriage and sexuality. Beginning in his home town of Putney, Vermont, he began to advocate what he called “complex marriage:” a form of communal marriage in which women and men who had achieved perfection could engage in sexual intercourse without sin. Noyes also promoted “male continence,” whereby men would not ejaculate, thereby freeing women from pregnancy and the difficulty of determining paternity when they had many partners. Intercourse became fused with spiritual power among Noyes and his followers.

The concept of complex marriage scandalized the townspeople in Putney, so Noyes and his followers removed to Oneida, New York. Individuals who wanted to join the Oneida Community underwent a tough screening process to weed out those who had not reached a state of perfection, which Noyes believed promoted self-control, not out-of-control behavior. The goal was a balance between individuals in a community of love and respect. The perfectionist community Noyes envisioned ultimately dissolved in 1881.

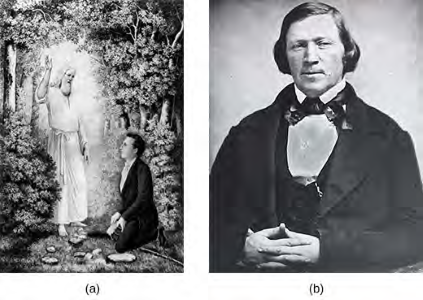

Joseph Smith and the Mormons

The most successful religious utopian community to arise in the antebellum years was begun by Joseph Smith. Smith came from a large Vermont family that had not prospered in the new market economy and moved to the town of Palmyra in western New York. In 1823, Smith claimed to have to been visited by the angel Moroni, who told him the location of a trove of golden plates or tablets. During the late 1820s, Smith translated the writing on the golden plates, and in 1830, he published his finding as The Book of Mormon. That same year, he organized the Church of Christ, the progenitor of the Church of Latter-Day Saints popularly known as Mormons. He presented himself as a prophet and aimed to recapture what he viewed as the purity of the primitive Christian church, purity that had been lost over the centuries. To Smith, this meant restoring male leadership.

Smith emphasized the importance of families being ruled by fathers. His vision of a reinvigorated

patriarchy resonated with men and women who had not thrived during the market revolution, and his claims attracted those who hoped for a better future. Smith’s new church placed great stress on work and discipline. He aimed to create a New Jerusalem where the church exercised oversight of its members.

Smith’s claims of translating the golden plates antagonized his neighbors in New York. Difficulties with anti-Mormons led him and his followers to move to Kirtland, Ohio, in 1831. By 1838, Smith and his followers were facing financial collapse after a series of efforts in banking and money-making ended in disaster. They moved to Missouri, but trouble soon developed there as well, as citizens reacted against the Mormons’ beliefs. Actual fighting broke out in 1838, and the ten thousand or so Mormons removed to Nauvoo, Illinois.

By the 1840s, Nauvoo boasted a population of thirty thousand, making it the largest utopian community in the United States. Thanks to some important conversions to Mormonism among powerful citizens in Illinois, the Mormons had virtual autonomy in Nauvoo, which they used to create the largest armed force in the state. Smith also received further revelations there, including one that allowed male church leaders to practice polygamy. He also declared that all of North and South America would be the new Zion and announced that he would run for president in 1844.

Smith and the Mormons’ convictions and practices generated a great deal of opposition from neighbors in surrounding towns. Smith was arrested for treason and, while he was in prison, an anti-Mormon mob stormed into his cell and killed him. Brigham Young then assumed leadership of the group, which he led to a permanent home in what is now Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secular Utopian Communities

Not all utopian communities were prompted by the religious fervor of the Second Great Awakening; some were outgrowths of the intellectual ideas of the time, such as romanticism with its emphasis on the importance of individualism over conformity. One of these, Brook Farm, took shape in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, in the 1840s. It was founded by George Ripley, a transcendentalist from Massachusetts. In the summer of 1841, this utopian community gained support from Boston-area thinkers and writers, an intellectual group that included many important transcendentalists. Brook Farm is best characterized as a community of intensely individualistic personalities who combined manual labor with intellectual pursuits. They opened a school that specialized in the liberal arts rather than rote memorization and published a weekly journal called The Harbinger, which was “Devoted to Social and Political Progress.” Members of Brook Farm never totaled more than one hundred, but it won renown largely because of the luminaries, such as Emerson and Thoreau, whose names were attached to it. Nathaniel Hawthorne, a Massachusetts writer who took issue with some of the transcendentalists’ claims, was a founding member of Brook Farm. In 1846, a fire destroyed the main building of Brook Farm, and already hampered by financial problems, the Brook Farm experiment came to an end in 1847.

Robert Owen, a British industrialist, helped inspire those who dreamed of a more equitable world in the face of the changes brought about by industrialization. Owen had risen to prominence by running cotton mills in Scotland. Owen was very uneasy about the conditions of workers, and he devoted both his life and his fortune to trying to create cooperative societies where workers would lead meaningful, fulfilled lives. Unlike the founders of many utopian communities, he did not gain inspiration from religion; his vision derived instead from his faith in human reason to make the world better.

When the Rappite community in Harmony, Indiana, decided to sell its holdings and relocate to

Pennsylvania, Owen seized the opportunity to put his ideas into action. In 1825, he bought the twenty-thousand-acre parcel in Indiana and renamed it New Harmony. After only a few years, however, a series of bad decisions by Owen and infighting over issues like the elimination of private property led to the dissolution of the community. But Owen’s ideas of cooperation and support inspired other “Owenite” communities in the United States.

A French philosopher who advocated the creation of a new type of utopian community, Charles Fourier also inspired American readers, notably Arthur Brisbane, who popularized Fourier’s ideas in the United States. Fourier emphasized collective effort by groups of people or “associations.” Members of the association would be housed in large buildings or “phalanxes,” a type of communal living arrangement. Converts to Fourier’s ideas about a new science of living published and lectured vigorously. They believed labor was a type of capital, and the more unpleasant the job, the higher the wages should be. Fourierists in the United States created some twenty-eight communities between 1841 and 1858, but by the late 1850s, the movement had run its course in the United States.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Utopian Communities

As 19th century America grew larger, richer, and more diverse, it was also trying to achieve a culture that was distinct and not imitative of any in Europe. At the same time, the thirst for individual improvement had local communities creating debating clubs, library societies, and literary associations for the purpose of sharing interesting and provocative ideas. Maybe, people speculated, if any society were completely reorganized, it could be regenerated and, ultimately, perfected. Utopia, originally a Greek word for an imaginary place where everyone and everything is perfect, was sought in America through the creation of model communities within the greater society.

Most of the original utopias were created for religious purposes. One of the earliest was devised by George Rapp, a German zealot, who took 600 followers to western Pennsylvania in 1804. Using shared funds to purchase land, the Rappites created a commune where they isolated themselves from others while waiting for the Revelation. Because of their extreme views on sex and marriage, and their strict, literal interpretation of the Bible, they failed to spread goodwill or gain converts.

Gradually, utopian communities came to reflect social perfectibility rather than religious purity. Robert Owen, for example, believed in economic and political equality. Those principles, plus the absence of a particular religious creed, were the 1825 founding principles of his New Harmony, Indiana, cooperative that lasted for only two years before economic failure. Charles Fourier, a French reformer and philosopher, set out the goal of social harmony through voluntary “phalanxes” that would be free of government interference and ultimately arise, unite and become a universal perfect society. John Humphrey Noyes designed Oneida Community in upstate New York. Oneidans experimented with group marriage, communal child rearing, group discipline, and attempts to improve the genetic composition of their offspring.

Self-reliance, optimism, individualism and a disregard for external authority and tradition characterized one of the most famous of all the American communal experiments. Brook Farm, near Roxbury, Massachusetts, was founded to promote human culture and brotherly cooperation. It was supposed to bestow the highest benefits of intellectual, physical, and moral education to all its members. Through hard work and simplicity, those who joined the fellowship of George Ripley’s farm were supposed to understand and live in social harmony, free of government, free to perfect themselves. However, Nathaniel Hawthorne, who wrote about his stay here in the Blithedale Romance, left this utopia disillusioned. Finally, it was romantic thinker and strict vegetarian Bronson Alcott, father of author Louisa May Alcott, who devoted himself to tilling the soil at fruitlands from June 1844 to January 1845 in the hope that love, education, and mutual labor would bring him and his small following peace. He was later ridiculed as “a man bent on saving the world by a return to acorns.”

The 1840s marked the height of the utopian trials. The belief that man was “naturally” good and that human institutions were perfectible had raised tremendous expectations about the possibilities of reform and renewal. These experiments ultimately disintegrated but, for a while, tried to be ideal places where a brotherhood of followers shared equally in the goods of their labor and lived in peace. It seemed that within the great American experiment, searching for utopia required only the commitment of people who found it easy to believe that nothing was impossible.

Source: U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium. Ushistory.org.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zzIofgZWk48

The Audiopedia. What is Owenism. (2016, October 16). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zzIofgZWk48

Summary

A number of utopian communities flourished in the United States in the early nineteenth century: George Rapp founded a utopian community rooted in biblical teachings in Pennsylvania; John Humphrey Noyes founded the Oneida community, which promoted complex marriage; Charles Fourier, a French philosopher, inspired the creation of a number of utopian communities across the United States; Robert Owen, a prominent socialist philosopher, inspired the creation of a number of utopian communities; the utopian community at Brook Farm provided inspiration for a number of transcendentalist thinkers.

While utopian communities were quite diverse, they all had one thing in common: a shared belief in that perfection was possible. Utopians were not seeking gradual reform or moderate improvements in society. Utopians were radicals seeking to create their own vision of a perfect world. Most of these utopian experiments faded out of existence within a few decades; few proved to be sustainable.