Slavery was a contentious and divisive issue throughout early American history. As the nation expanded in the early-to-mid nineteenth century, there was a fierce dispute over the expansion of slavery. The northern states opposed the expansion of slavery, while southern states advocated the expansion of slavery into newly acquired territories.

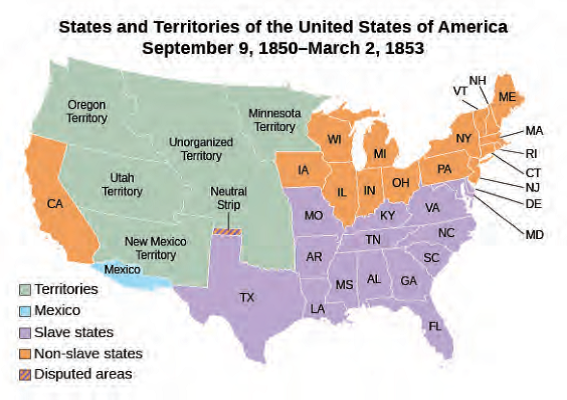

The acquisition of the Louisiana Territory and the Mexican Cession created crises that ultimately resulted in compromise. In 1820, the Missouri Compromise established boundaries for the expansion of slavery into the Louisiana Territory. The Compromise of 1850 established boundaries limiting the expansion of slavery in the land gained through the Mexican Cession.

The Supreme Court ultimately undermined these efforts to reach a compromise on the expansion of slavery. In the Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could not prohibit slavery in any territory, as this violated the property rights of slave-owners. This decision helped propel the nation to Civil War.

Dred Scott

Another stage of U.S. expansion took place when inhabitants of Missouri began petitioning for statehood beginning in 1817. The Missouri territory had been part of the Louisiana Purchase and was the first part of that vast acquisition to apply for statehood. By 1818, tens of thousands of settlers had flocked to Missouri, including slaveholders who brought with them some ten thousand slaves. When the status of the Missouri territory was taken up in earnest in the U.S. House of Representatives in early 1819, its admission to the Union proved to be no easy matter, since it brought to the surface a violent debate over whether slavery would be allowed in the new state.

Admitting Missouri as a slave state would threaten the tenuous balance between free and slave states in the Senate by giving slave states a two-vote advantage.

The debate about representation shifted to the morality of slavery itself when New York representative James Tallmadge, an opponent of slavery, attempted to amend the statehood bill in the House of Representatives. Tallmadge proposed that Missouri be admitted as a free state, that no more slaves be allowed to enter Missouri after it achieved statehood, and that all enslaved children born there after its admission be freed at age twenty-five.

Northern representatives supported the Tallmadge Amendment, denouncing slavery as immoral and opposed to the nation’s founding principles of equality and liberty. Southerners in Congress rejected the amendment as an attempt to gradually abolish slavery—not just in Missouri but throughout the Union—by violating the property rights of slaveholders and their freedom to take their property wherever they wished. Slavery’s apologists, who had long argued that slavery was a necessary evil, now began to perpetuate the idea that slavery was a positive good for the United States. They asserted that it generated wealth and left white men free to exercise their true talents instead of toiling in the soil. Slaves were cared for, supporters argued, and were better off exposed to the teachings of Christianity as slaves than living as free heathens in uncivilized Africa. Above all, the United States had a destiny, they argued, to create an empire of slavery throughout the Americas.

Most disturbing for the unity of the young nation, however, was that debaters divided along sectional lines, not party lines. With only a few exceptions, northerners supported the Tallmadge Amendment regardless of party affiliation, and southerners opposed it despite having party differences on other matters. It did not pass, and the crisis over Missouri led to strident calls of disunion and threats of civil war.

Congress finally came to an agreement, called the Missouri Compromise, in 1820. Missouri and Maine would enter the Union at the same time, Maine as a free state, Missouri as a slave state. The Tallmadge Amendment was narrowly rejected, the balance between free and slave states was maintained in the Senate, and southerners did not have to fear that Missouri slaveholders would be deprived of their human property. To prevent similar conflicts each time a territory applied for statehood, a line coinciding with the southern border of Missouri (at latitude 36° 30′) was drawn across the remainder of the Louisiana Territory. Slavery could exist south of this line but was forbidden north of it, with the obvious exception of Missouri.

Source: Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Compromise of 1850

The election of 1848 did nothing to quell the controversy over whether slavery would advance into the Mexican Cession. Some slaveholders, like President Taylor, considered the question a moot point because the lands acquired from Mexico were far too dry for growing cotton and therefore, they thought, no slaveholder would want to move there. Other southerners, however, argued that the question was not whether slaveholders would want to move to the lands of the Mexican Cession, but whether they could and still retain control of their slave property. Denying them the right to freely relocate with their lawful property was, they maintained, unfair and unconstitutional. Northerners argued, just as fervidly, that because Mexico had abolished slavery, no slaves currently lived in the Mexican Cession, and to introduce slavery there would extend it to a new territory, thus furthering the institution and giving the Slave Power more control over the United States. The strong current of antislavery sentiment only increased the opposition to the expansion of slavery into the West.

Most northerners, except members of the Free-Soil Party, favored popular sovereignty for California and the New Mexico territory. Many southerners opposed this position, however, for they feared residents of these regions might choose to outlaw slavery. Some southern politicians spoke ominously of secession from the United States. Free-Soilers rejected popular sovereignty and demanded that slavery be permanently excluded from the territories.

Beginning in January 1850, Congress worked for eight months on a compromise that might quiet the growing sectional conflict. Led by the aged Henry Clay, members finally agreed to the following:

- California, which was ready to enter the Union, was admitted as a free state in accordance with its state constitution.

- Popular sovereignty was to determine the status of slavery in New Mexico and Utah, even though Utah and part of New Mexico were north of theMissouri Compromise line.

- The slave trade was banned in the nation’s capital. Slavery, however, was allowed to remain.

- Under a new fugitive slave law, those who helped runaway slaves or refused to assist in their return would be fined and possibly imprisoned.

The Compromise of 1850 brought temporary relief. It resolved the issue of slavery in the territories for the moment and prevented secession. The peace would not last, however.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

As president, Buchanan confronted a difficult and volatile situation. The nation needed a strong personality to lead it, and Buchanan did not possess this trait. The violence in Kansas demonstrated that applying popular sovereignty—the democratic principle of majority rule—to the territory offered no solution to the national battle over slavery. A decision by the Supreme Court in 1857, which concerned the slave Dred Scott, only deepened the crisis.

In 1857, several months after President Buchanan took the oath of office, the Supreme Court ruled in Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred Scott, born a slave in Virginia in 1795, had been one of the thousands forced to relocate as a result of the massive internal slave trade and taken to Missouri, where slavery had been adopted as part of the Missouri Compromise. In 1820, Scott’s owner took him first to Illinois and then to the Wisconsin territory. However, both of those regions were part of the Northwest Territory, where the 1787 Northwest Ordinance had prohibited slavery. When Scott returned to Missouri, he attempted to buy his freedom. After his owner refused, he sought relief in the state courts, arguing that by virtue of having lived in areas where slavery was banned, he should be free.

In a complicated set of legal decisions, a jury found that Scott, along with his wife and two children, were free. However, on appeal from Scott’s owner, the state Superior Court reversed the decision, and the Scotts remained slaves. Scott then became the property of John Sanford, who lived in New York. He continued his legal battle, and because the issue involved Missouri and New York, the case fell under the jurisdiction of the federal court. In 1854, Scott lost in federal court and appealed to the United States Supreme Court.

In 1857, the Supreme Court—led by Chief Justice Roger Taney, a former slaveholder who had freed his slaves—handed down its decision. On the question of whether Scott was free, the Supreme Court decided he remained a slave. The court then went beyond the specific issue of Scott’s freedom to make a sweeping and momentous judgment about the status of blacks, both free and slave. Per the court, blacks could never be citizens of the United States. Further, the court ruled that Congress had no authority to stop or limit the spread of slavery into American territories. This proslavery ruling explicitly made the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional; implicitly, it made Douglas’s popular sovereignty unconstitutional.

The Dred Scott decision infuriated Republicans by rendering their goal—to prevent slavery’s spread into the territories—unconstitutional. To Republicans, the decision offered further proof of the reach of the South’s Slave Power, which now apparently extended even to the Supreme Court. The decision also complicated life for northern Democrats, especially Stephen Douglas, who could no longer sell popular sovereignty as a symbolic concession to southerners from northern voters. Few northerners favoured slavery’s expansion westward.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Dred Scott – video

Foner, E. The Compromise of 1850: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1850-1861. (2014, October 27). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwralA6-yHM

Foner, E. The Dr-ed Scott Case: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1850-1861. (2014, November 12). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mRaA0GQgobI

Summary

The United States was deeply divided over the issue of slavery in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. Northern political leaders opposed to the expansion of slavery, while southern political leaders supported the expansion of slavery. In 1820, under the Missouri Compromise, Missouri was admitted to the Union as a slave state. In the Compromise of 1850, California was admitted to the Union as a free state. The case of Dred Scott further exacerbated the dispute over slavery. Dred Scott was born into slavery in Virginia, but his master later took him to the free territory of Wisconsin. Dred Scott sued for his freedom. In a scandalous ruling, the Supreme Court, under the leadership of Chief Justice Roger Taney, ruled that Dred Scott was not a citizen of the United States because he was African American. Further, the Court ruled that the federal government did not have the power to prohibit slavery in any territory.