When Christopher Columbus arrived in the “New World” in 1492, he “discovered” a world that had already been inhabited by indigenous peoples for thousands of years. According to the most recent archaeological and genetic evidence, the ancestors of Native-Americans crossed the Bering Strait from Siberia into present-day Alaska between 12,000 and 20,000 years ago. After several waves of migration across the Bering Strait, rising sea levels effectively cut the Americas off from Asia around 16,500 years ago. Over time, Paleo-Indians prospered in the Americas, developing rich, diverse and complex civilizations, speaking over 2000 distinct languages and dialects, and inhabiting nearly every region of the Americas. Scholars estimate that upon Columbus’ arrival in the Americas, there were between 2.1 to 18 million indigenous peoples living in North and South America. Their rich civilizations played a central, and often underappreciated, role in the history of North America.

Native America

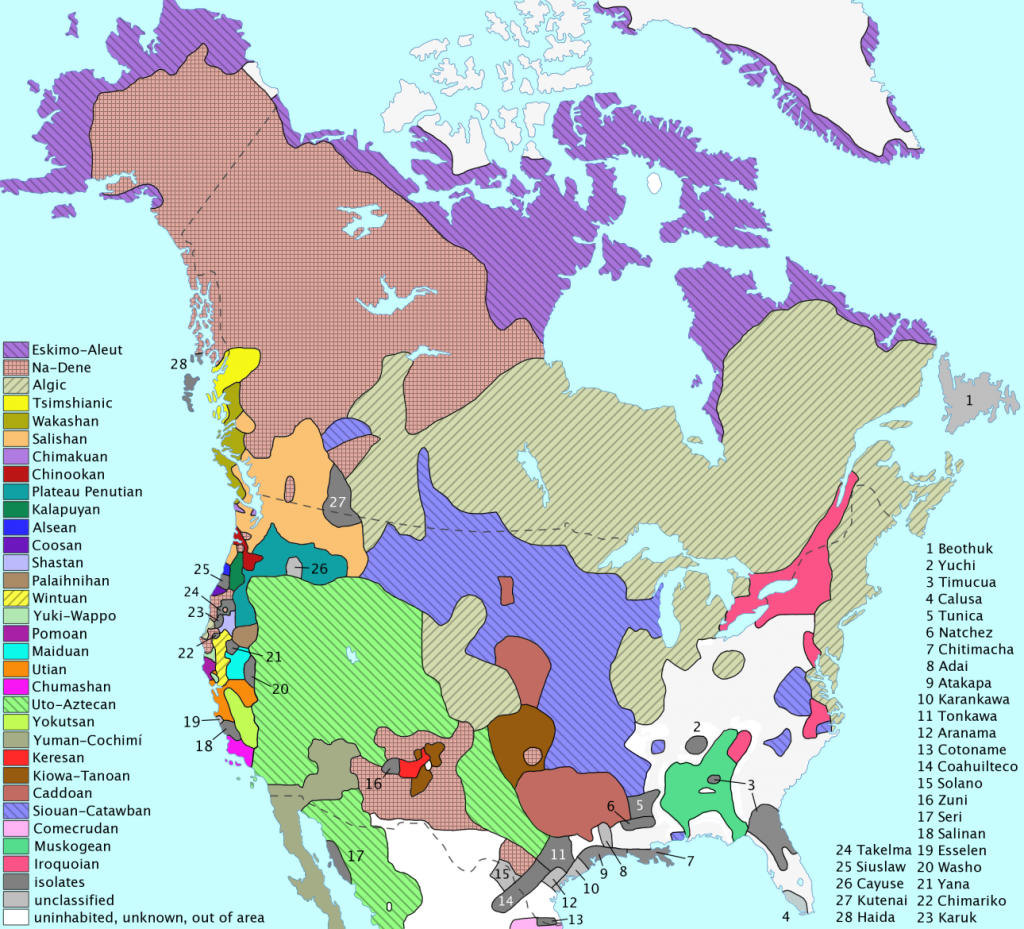

American history begins with the first Americans. But where do their stories start? Archaeologists and anthropologists focus on migration histories. Studying artifacts, bones, and genetic signatures, these scholars have pieced together a narrative that claims that the Americas were once a “new world” for Native Americans as well. The last global ice age trapped much of the world’s water in enormous continental glaciers. Twenty thousand years ago, ice sheets, some a mile thick, extended across North America as far south as modern-day Illinois. With so much of the world’s water captured in these massive ice sheets, global sea levels were much lower, and a land bridge connected Asia and North America across the Bering Strait. Between twelve and twenty thousand years ago, Native ancestors crossed the ice, waters, and exposed lands between the continents of Asia and America. DNA evidence suggests that these ancestors paused—for perhaps 15,000 years—in the expansive region between Asia and America. Other ancestors crossed the seas and voyaged along the Pacific coast, traveling along riverways and settling where local ecosystems permitted. Glacial sheets receded around fourteen thousand years ago, opening a corridor to warmer climates and new resources. Some ancestral communities migrated south and eastward. Evidence found at Monte Verde, a site in modern-day Chile, suggests human activity began there at least 14,500 years ago. Similar evidence hints at human settlement in the Florida panhandle at the same time. On many points, archaeological and traditional knowledge sources converge: the dental, archaeological, linguistic, oral, ecological and genetic evidence illustrates a great deal of diversity, with numerous different groups settling and migrating over thousands of years, potentially from many different points of origin.

In the Northwest, Native groups exploited the great salmon-filled rivers. On the plains and prairie lands, hunting communities followed bison herds and moved according to seasonal patterns. In mountains, prairies, deserts, and forests, the cultures and ways of life of paleo-era ancestors were as varied as the geography. These groups spoke hundreds of languages and adopted distinct cultural practices. Rich and diverse diets fueled massive population growth across the continent.

Agriculture arose sometime between nine- and five-thousand years ago, almost simultaneously in the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. Mesoamericans in modern-day Mexico and Central America relied upon domesticated maize (corn) to develop the hemisphere’s first settled population around 1,200 BCE. Corn was high in caloric content, easily dried and stored, and, in Mesoamerica’s warm and fertile Gulf Coast, could sometimes be harvested twice in a year. Corn—as well as other Mesoamerican crops—spread across North America and continues to hold an important spiritual and cultural place in many Native communities.

Agriculture flourished in the fertile river valleys between the Mississippi River and Atlantic Ocean, an area known as the Eastern Woodlands. There, three crops in particular–corn, beans, and squash, known as the “Three Sisters”–provided nutritional needs necessary to sustain cities and civilizations. Many groups used shifting cultivation where farmers cut the forest, burned the undergrowth and then planted seeds in the nutrient rich ashes. When crop yields began to decline, farmers would move to another field and allow the land to recover and the forest to regrow before again cutting the forest, burning the undergrowth, and restarting the cycle. This technique was particularly useful in areas with difficult soil. But in the fertile regions of the Eastern Woodlands, Native American farmers engaged in permanent, intensive agriculture, using hand tools rather than European-style plows. The rich soil and use of hand-tools enabled effective and sustainable farming practices, producing high yields without overburdening the soil. Along the Mississippi River, the Mississippians developed one of the largest civilizations north of modern-day Mexico. Roughly one-thousand years ago, the largest Mississippian settlement, Cahokia, located just east of modern-day St. Louis, peaked at a population of between 10,000-30,000. It rivaled contemporary European cities in size. No American city, in fact, would match Cahokia’s peak population levels until after the American Revolution. The city itself spanned 2,000 acres and centered around Monks Mound, a large earthen hill that rose ten-stories and was larger at its base than the great pyramids of Egypt.

North America’s indigenous peoples shared some broad traits. Spiritual practices, understandings of property, and kinship networks differed markedly from European arrangements. Most Native Americans did not neatly distinguish between the natural and the supernatural. Spiritual power permeated their world and was both tangible and accessible. It could be appealed to and harnessed. Kinship bound most Native North American people together. Most peoples lived in small communities tied by kinship networks. Many Native cultures understood ancestry as matrilineal: family and clan identity proceeded along the female line, through mothers and daughters, rather than fathers and sons. Fathers, for instance, would often join mothers’ extended families and sometimes even a mother’s brothers would take a more direct role in child-raising than biological fathers. Mothers could therefore often wield enormous influence at local levels and men’s identities and influence often depended on their relationships to women. Native American culture meanwhile generally afforded greater sexual and marital freedom than European cultures did. Women often chose their husbands, and divorce often was a relatively simple and straightforward process. Moreover, most Native peoples’ notions of property rights differed markedly from Europeans’ notions of property. Native Americans generally felt a personal ownership of tools, weapons, or other items that were actively used, and this same rule applied to land and crops. Groups and individuals exploited particular pieces of land, and used violence or negotiation to exclude others. But the right to the use of land did not imply the right to its permanent possession.

Native Americans had many ways of communicating, including graphic ones, and some of these artistic and communicative technologies are still used today. For example, Algonkian-speaking Ojibwes, used birch-bark scrolls to record medical treatments, recipes, songs, stories, and more. Other Eastern Woodland peoples wove plant fibers, embroidered skins with porcupine quills, and modeled the earth to make sites of complex ceremonial meaning. On the Plains, artisans wove buffalo hair and painted on buffalo skins; in the Pacific Northwest weavers wove goat hair into soft textiles with particular patterns. Maya, Zapotec, and Nahua ancestors in Mesoamerica painted their histories on plant-derived textiles and carved them into stone. In the Andes, Inka recorders noted information in the form of knotted strings, or Khipu.

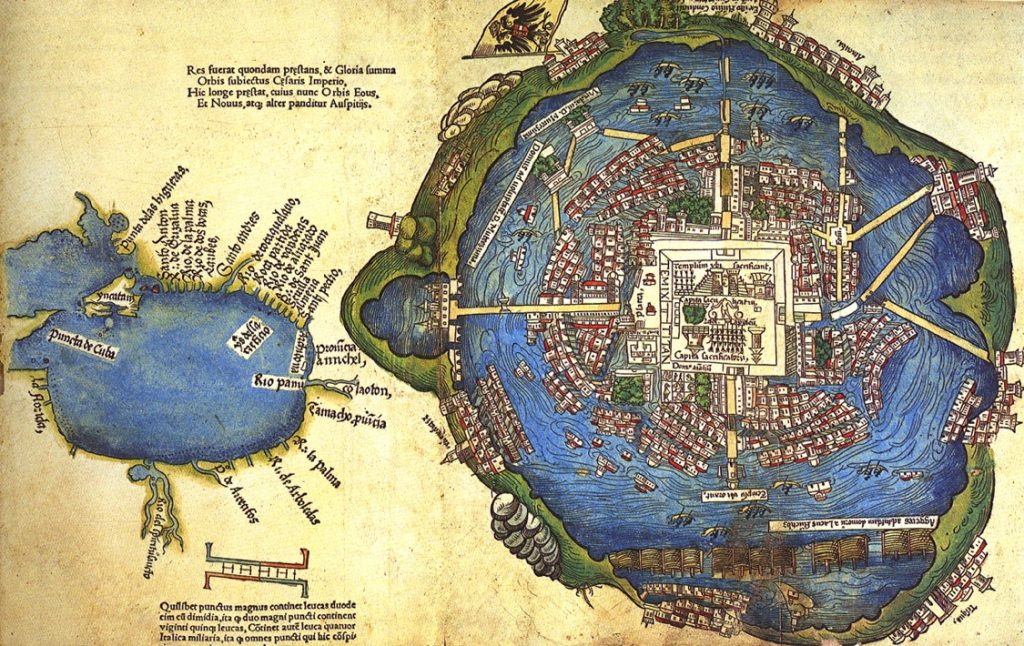

Two thousand years ago, some of the largest culture groups in North America were the Puebloan groups, centered in the current-day Greater Southwest (the southwestern US and northwestern Mexico), the Mississippian groups located along the Great River and its Woodland tributaries, and the Mesoamerican groups of the areas now known as central Mexico and the Yucatan. Previous developments in agricultural technology enabled the explosive growth of the large early societies, such as that at Tenochtitlan in the Central Mexican Valley, Cahokia along the Mississippi River, and in the desert oasis areas of the Greater Southwest.

Source: L.D. Burnett et al., “The New World,” Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Native America – Video

Native America

Citation: Khan Academy. 2017, January 27. Pre Columbian Americas. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2XjXFvruIM

Summary

Despite commonalities, Native cultures varied greatly. The New World was marked by diversity and contrast. By the time Europeans were poised to cross the Atlantic, Native Americans spoke hundreds of languages and lived in keeping with the hemisphere’s many climates. Some lived in cities, others in small bands. Some migrated seasonally, others settled permanently. Over time, Europeans would attempt to delegitimize Native American claims to territory and, based on their preconceptions about religion, gender roles, and society, claim Native Americans were “savages.” Nothing could have been further from the truth. All Native peoples had long histories and rich, well-formed, and varied cultures that developed over millennia. When Europeans first encountered them, Native American civilizations rivaled the most sophisticated and large societies back in Europe. Although they were by no means inferior, they were distinct from their European equivalents. Those distinctions would trigger nearly three centuries of conflict, mutual misunderstanding, and warfare.

In conclusion, Native Americans were the original “discoverers” of America in prehistoric human history. After arriving in North America from modern-day Siberia, they populated North and South America over time, developed rich and diverse societies, and created multiple cities and civilizations across the Americas, such as the Mississippian culture along the Mississippi River.

Sections of this text are excerpts from L.D. Burnett et al., “The New World,” Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified Augus