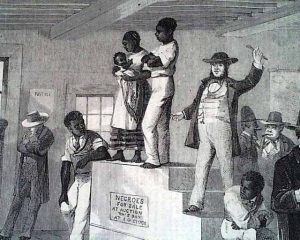

Africans were the immigrants to the British New World that had no choice in their destinations or destinies. The first African Americans that arrived in Jamestown in 1619 on a Dutch trading ship were not slaves, nor were they free. They served time as indentured servants until their obligations were complete. Although these lucky individuals lived out the remainder of their lives as free men, the passing decades would make this a rarity. Despite the complete lack of a slave tradition in mother England, slavery gradually replaced indentured servitude as the chief means for plantation labor in the Old South.

Virginia would become the first British colony to legally establish slavery in 1661. Maryland and the Carolinas were soon to follow. The only Southern colony to resist the onset of slavery was Georgia, created as an Enlightened experiment. Seventeen years after its formation, Georgia too succumbed to the pressures of its own citizens and repealed the ban on African slavery. Laws soon passed in these areas that condemned all children of African slaves to lifetimes in chains.

Source: U.S. History.org

Labor and the Law

Slavery in the colonial United States (1600–1776) developed from complex factors, and several theories have been proposed to explain development of the trade and institution. Slavery was strongly associated with the European colonies’ need for labor, especially for the labor-intensive plantation economies.

Most slaves who were brought or kidnapped to the Thirteen British colonies, which later became the Eastern seaboard of the United States, were imported from the Caribbean, not directly from Africa. They were predominately transported to the Caribbean islands as a result of the Atlantic slave trade. Indigenous people were also enslaved in the North American colonies, but on a much smaller scale, and Indian slavery ended in the eighteenth century. In the English colonies, slave status for Africans became hereditary in the mid-17th century and passage of colonial laws that defined children born in the colonies as taking the status of the mother.

While the British knew about Spanish and Portuguese slave trading, they did not implement slave labor in the Americas until the 17th century.

In 1607, England established Jamestown as its first permanent colony on the North American continent. Tobacco became the chief commodity crop of the colony, due to the efforts of John Rolfe in 1611. Once it became clear that tobacco was going to drive the Jamestown economy, more workers were needed for the labor-intensive crop. The British aristocracy also needed to find a labor force to work on its sugar plantations in the Americas. The major sources were indentured servants from Britain, Native Americans, and West Africans. During this period, Barbados became an English Colony in 1624 and the Caribbean’s Jamaica in 1655. These and other Caribbean colonies became the center of wealth generated from sugar cane and the focus of the slave trade for the growing English empire.

At first, indentured servants were used as the needed labor. These servants provided up to seven years of service in exchange for having their trip to Jamestown paid for by someone in Jamestown. Once the seven years was over, the indentured servant was free to live in Jamestown as a regular citizen. However, colonists began to see indentured servants as too costly, in part because the high mortality rate meant the force had to be resupplied. In 1619, Dutch traders brought African slaves taken from a Spanish ship to Jamestown; in North America, the Africans were also generally treated as indentured servants in the early colonial era.

Until the early 18th century, enslaved Africans were difficult to acquire in the colonies that became the United States, as most were sold to the West Indies, where the large plantations and high mortality rates required continued importation of slaves. One of the first major centers of African slavery in the English North American colonies occurred with the founding of Charles Town and the Province of Carolina in 1670. The colony was founded mainly by planters from the overpopulated British sugar island of Barbados, who brought relatively large numbers of African slaves from that island to establish new plantations.

For several decades it was difficult for planters north of the Caribbean to acquire African slaves. To meet agricultural labor needs, colonists practiced Indian slavery for some time. The Carolinians transformed the Indian slave trade during the late 17th and early 18th centuries by treating such slaves as a trade commodity to be exported, mainly to the West Indies. Historian Alan Gallay estimates that between 1670 and 1715, between 24,000 and 51,000 captive Native Americans were exported from South Carolina—much more than the number of Africans imported to the colonies of the future United States during the same period.

The first Africans to be brought to British North America landed in Virginia in 1619. They arrived on a Dutch ship that had captured them from the Spanish. These approximately 20 individuals appear to have been treated as indentured servants, and a significant number of enslaved Africans earned freedom by fulfilling a work contract or for converting to Christianity. Some successful free people of color, such as Anthony Johnson, in turn acquired slaves or indentured servants for workers. Historians such as Edmund Morgan say this evidence suggests that racial attitudes were much more flexible in 17th-century Virginia than they would later become. A 1625 census recorded 23 Africans in Virginia. In 1649 there were 300, and in 1690 there were 950.

The barriers of slavery hardened in the Second half of the 17th century, and imported Africans’ prospects grew increasingly dim. By 1640, the Virginia courts had sentenced at least one black servant, John Punch, to slavery. In 1656 Elizabeth Key won a suit for freedom based on her father’s status as a free Englishman, and his having baptized her as Christian in the Church of England. In 1662 the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law with the doctrine of partus, stating that any child born in the colony would follow the status of its mother, bond or free. This was an overturn of a longheld principle of English Common Law, whereby a child’s status followed that of the father. It enabled slaveholders and other white men to hide the mixed-race children born of their rape of slave women and removed their responsibility to acknowledge, support, or emancipate the children.

During the second half of the 17th century, the British economy improved and the supply of British indentured servants declined, as poor Britons had better economic opportunities at home. At the same time, Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 led planters to worry about the prospective dangers of creating a large class of restless, landless, and relatively poor white men (most of them former indentured servants). Wealthy Virginia and Maryland planters began to buy slaves in preference to indentured servants during the 1660s and 1670s, and poorer planters followed suit by c.1700. (Slaves cost more than servants, so initially only the wealthy could invest in slaves.) The first British colonists in Carolina introduced African slavery into the colony in 1670, the year the colony was founded, and Charleston ultimately became the busiest slave port in North America. Slavery spread from the South Carolina Low country first to Georgia, then across the Deep South as Virginia’s influence had crossed the Appalachians to Kentucky and Tennessee. Northerners also purchased slaves, though on a much smaller scale. Enslaved people outnumbered free whites in South Carolina from the early 1700s to the Civil War. An authoritarian political culture evolved to prevent slave rebellion and justify white slave holding. Northern slaves typically dwelled in towns, rather than on plantations as in the South, and worked as artisans and artisans’ assistants, sailors and longshoremen, and domestic servants.

In 1672, King Charles II rechartered the Royal African Company (it had initially been set up in 1660), as an English monopoly for the African slave and commodities trade—thereafter in 1698, by statute, the English parliament opened the trade to all English subjects. The slave trade to the mid-Atlantic colonies increased substantially in the 1680s, and by 1710 the African population in Virginia had increased to 23,100 (42% of total); Maryland contained 8,000 Africans (23% of total). In the early 18th century, England passed Spain and Portugal to become the world’s leading slave-trader.

The North American royal colonies not only imported Africans but also captured Native Americans, impressing them into slavery. Many Native Americans were shipped as slaves to the Caribbean. Many of these slaves from the British colonies were able to escape by heading south, to the Spanish colony of Florida. There they were given their freedom, if they declared their allegiance to the King of Spain and accepted the Catholic Church. In 1739 Fort Mose was established by African American freedmen and became the northern defense post for St. Augustine. In 1740, English forces attacked and destroyed the fort, which was rebuilt in 1752. Because Fort Mose became a haven for escaped slaves from the English colonies to the north, it is considered a precursor site of the Underground Railroad.

Curiously, chattel slavery developed in British North America before the legal apparatus that supported slavery did. During the late 17th century and early 18th century, harsh new slave codes limited the rights of African slaves and cut off their avenues to freedom. The first full-scale slave code in British North America was South Carolina’s (1696), which was modeled on the colonial Barbados slave code of 1661 and was updated and expanded regularly throughout the 18th century.

A 1691 Virginia law prohibited slaveholders from emancipating slaves unless they paid for the freedmen’s transportation out of Virginia. Virginia criminalized interracial marriage in 1691, and subsequent laws abolished blacks’ rights to vote, hold office, and bear arms. Virginia’s House of Burgesses established the basic legal framework for slavery in 1705.

Source: Slavery in the United States. Wikipedia. Retrieved from http://en.turkcewiki.org/wiki/Slavery_in_the_United_States

Labor and the Law – video

Foner, E. American Slavery: The Origins of Slavery. Slavery in Colonial Virginia. (8 October 2014). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z6uPW63mvBQ

Summary

In seventeenth century Virginia, there was a tremendous demand for agricultural laborers to harvest tobacco. In 1619, a Dutch trade ship arrive in port with approximately 20 African Americans. As the British colony did not yet have any system of slavery, this initial group of African Americans were treated as indentured servants who would eventually gain their freedom. In 1661, Virginia became the first state in British colonial North America to legally recognize slavery. Soon thereafter, in 1662, a law was passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses stating that the condition of a child (slave or free) was dependent on the status of the mother, which made slavery a hereditary status passed from generation to generation. Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676 led planters to worry about the prospective dangers of creating a large class of restless, landless, and relatively poor white men (most of them former indentured servants). This contributed to a shift from indentured servitude towards slavery labor in the colony. By 1710, over 40 percent of the population of the Virginia colony was African American.