After the War of 1812, Americans expanded rapidly into the Great Lakes region, Florida in the South, and westward across the Appalachian Mountains thanks in part to aggressive land sales by the federal government. Little settlement occurred west of Missouri as migrants viewed the Great Plains as a barrier to farming. Further west, the Rocky Mountains loomed as undesirable to all but fur traders, and all American Indians west of the Mississippi appeared too powerful to allow for white expansion. However, these lands were not empty. American Indians controlled much of the land east of the Mississippi River and almost all the West. Expansion hinged on a federal policy of Indian removal. The harassment and dispossession of American Indians – whether driven by official U.S. government policy or the actions of individual Americans and their communities – depended on the belief in manifest destiny. Of course, a fair bit of racism was part of the equation as well. The political and legal processes of expansion always hinged on the belief that white Americans could best use new lands and opportunities. This belief rested upon the belief that only Americans embodied the democratic ideals of yeoman agriculturalism extolled by Thomas Jefferson and expanded under Jacksonian democracy.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Expansion

Florida was an early test case for the Americanization of new lands. The territory held strategic value for the young nation’s growing economic and military interests in the Caribbean. The most important factors that led to the annexation of Florida included anxieties over runaway slaves, Spanish neglect of the region, and the desired defeat of Native American tribes who controlled large portions of lucrative farm territory. The United States had also already acquired lands west of Florida, including Louisiana, which had become a state in 1812, as a result of the Louisiana Purchase and the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War in the 1760s, and setters were beginning to pay increased attention to the rich farmland east of Louisiana.

During the early 19th century, Spain wanted to increase productivity in Florida and encouraged migration of mostly Southern slave owners. By the second decade of the 1800s, Anglo settlers occupied plantations along the St. Johns River, from the border with Georgia to Lake George 100 miles upstream. Spain began to lose control as the area quickly became a haven for slave smugglers bringing illicit human cargo into the U.S. for lucrative sale to Georgia planters. Plantation owners grew apprehensive about the growing numbers of slaves running to the swamps and Indian-controlled areas of Florida. American slave owners pressured the U.S. government to confront the Spanish authorities. Southern slave owners refused to quietly accept the continued presence of armed black men in Florida. During the War of 1812, a ragtag assortment of Georgia slave owners joined by a plethora of armed opportunists raided Spanish and British-owned plantations along the St. Johns River. These private citizens received U.S. government help on July 27, 1816, when U.S. army regulars attacked the Negro Fort (established as an armed outpost during the war by the British and located about 60 miles south of the Georgia border). The raid killed 270 of the fort’s inhabitants as a result of a direct hit on the fort’s gun powder stores. This conflict set the stage for General Andrew Jackson’s invasion of Florida in 1817 and the beginning of the First Seminole War.

“Portrait of Benjamin Hawkins (1754-1818) on his plantation along the Flint River in central Georgia” from Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC PD Mark

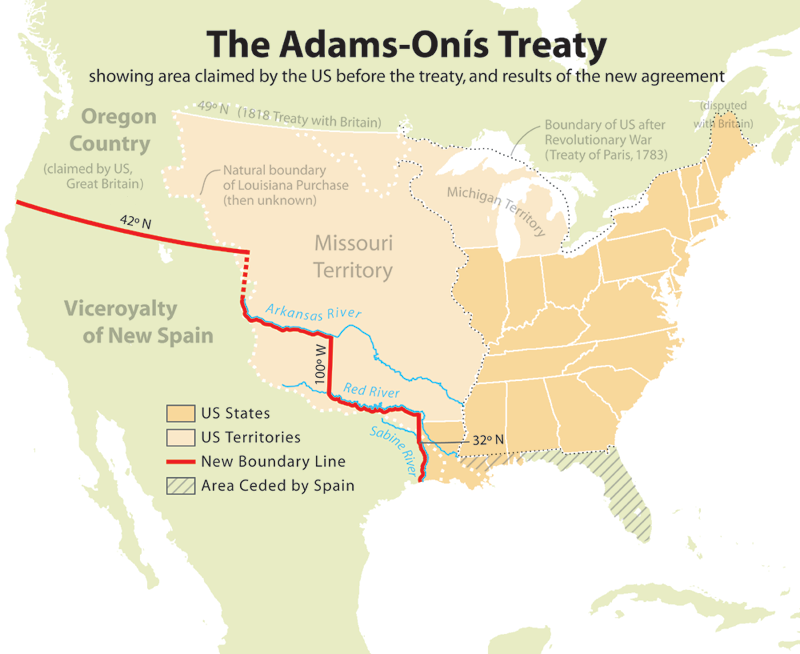

Americans also held that Creek and Seminole Indians, occupying the area from the Apalachicola River to the wet prairies and hammock islands of central Florida, were dangers in their own right. These tribes, known to the Americans collectively as “Seminoles,” migrated into the region over the course of the 18th century and established settlements, tilled fields, and tended herds of cattle in the rich floodplains and grasslands that dominated the northern third of the Florida peninsula. Envious eyes looked upon these lands. After bitter conflict that often pitted Americans against a collection of Native Americans and former slaves, Spain eventually agreed to transfer the territory to the U.S. The resulting Adams-Onís Treaty exchanged Florida for $5 million and other territorial concessions elsewhere. After the purchase, planters from the Carolinas, Georgia, and Virginia entered Florida. However, the influx of settlers into the Florida territory was temporarily halted in the mid-1830s by the outbreak of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). Free black men and women and escaped slaves also occupied the Seminole district; a situation that deeply troubled slave owners. Indeed, General Thomas Sidney Jesup, U.S. commander during the early stages of the Second Seminole War, labeled that conflict “a negro, not an Indian War,” fearful as he was that if the revolt, “was not speedily put down, the South will feel the effect of it on their slave population before the end of the next season.” Florida became a state in 1845 and settlement expanded into the former Indian lands.

Beginning in 1826, Georgian officials asked the federal government to negotiate with the Cherokee to secure lucrative lands. The Adams’ administration resisted the state’s request, but harassment from local settlers against the Cherokee forced the Adams and then Jackson administrations to begin serious negotiations with the Cherokees. Georgia grew impatient with the process of negotiation and abolished existing state agreements with the Cherokee that had guaranteed rights of movement and jurisdiction of tribal law. Andrew Jackson penned a letter soon after taking office that encouraged the Cherokee, among others, to voluntarily relocate to the West. The discovery of gold in Georgia in the fall of 1829 further antagonized the situation.

The Cherokee defended themselves against Georgia’s laws by citing treaties signed with the United States that guaranteed the Cherokee nation both their land and independence. The Cherokee appealed to the Supreme Court against Georgia to prevent dispossession. The Court, while sympathizing with the Cherokees’ plight, ruled that it lacked jurisdiction to hear the case (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia – 1831). In an associated case, Worcester v. Georgia 1832, The Supreme Court ruled that Georgia laws did not apply within Cherokee territory. Regardless of these rulings, the state government ignored the Supreme Court and did little to prevent conflict between settlers and the Cherokee.

In 1835, a portion of the Cherokee Nation led by John Ridge, hoping to prevent further tribal bloodshed signed the Treaty of New Echota. This treaty ceded lands in Georgia for five million dollars and, the signatories hoped, limiting future conflicts between the Cherokee and white settlers. However, most of the tribe refused to adhere to the terms, viewing the treaty as illegitimately negotiated. In response, John Ross pointed out the U.S. government’s hypocrisy. “You asked us to throw off the hunter and warrior state: We did so—you asked us to form a republican government: We did so. Adopting your own as our model. You asked us to cultivate the earth, and learn the mechanic arts. We did so. You asked us to learn to read. We did so. You asked us to cast away our idols and worship your god. We did so. Now you demand we cede to you our lands. That we will not do.”

Railroads wouldn’t create the desire to settle the West, but they did make it possible for people who wanted to live out West to do so for two reasons. First, without railroads there would be no way to bring crops or other goods to market. Second, railroads made life in the West profitable and livable because they brought the goods that people needed, such as tools for planting and sowing, shoes for wearing, books for putting on your shelf and pretending to have read. Railroads allowed settlers to stay connected with the modernity that was becoming the hallmark of the industrialized world in the 19th century.

The federal government played a key role in financing the transcontinental railroad, but perhaps the central way that the federal government supported the railroads in Western settlement and investment in general was by leading military expeditions against American Indians, rounding them up on ever-smaller reservations and destroying their culture. There was an economic as well as a racial imperative to move the Native Americans off western lands: initially, it was needed to set down railroad tracks and then for farming but eventually it was also exploited for minerals like gold and iron and other stuff that makes industry work.

Early Western settlement of the Oregon Trail kind did not result in huge conflicts with Native Americans, but by the 1850s a steady stream of settlers kicked off increasingly bloody conflicts that lasted pretty much until 1890. Even though the fighting started before the Civil War, the end of the war between the states meant a new, more violent phase in the warring between American Indians and whites. General Philip H. “Little Phil” Sheridan set out to destroy the Indians’ way of life, burning villages and killing their horses and especially the buffalo that was the basis of the plains tribes’ existence. There were about 30 million buffalo in the US in 1800, by 1886 the Smithsonian Institute had difficulty finding 25 good specimens.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com and CrashCourse, “Westward Expansion,” 8 August 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q16OZkgSXfM.

Expansion – Video

Expansion

Crash Course US History. 2013, February 8. Westward Expansion. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q16OZkgSXfM

Summary

The allure of manifest destiny encouraged expansion regardless of terrain or locale, and Indian removal also took place, to a lesser degree, in northern lands. In the Old Northwest, Odawa and Ojibwe communities in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, resisted removal as many lived on land north of desirable farming land. Moreover, some Ojibwe and Odawa individuals purchased land independently. They formed successful alliances with missionaries to help advocate against removal, as well as some traders and merchants who depended on trade with Native peoples. Yet, Indian removal occurred in the North as well—the “Black Hawk War” in 1832, for instance, led to the removal of many Sauk to Kansas.

Across the North American continent, American settlers and the federal government encountered Native Americans like the Odawa and Ojibwe, used treaties or brute force to purchase new lands, and over the course of a century significantly expanded the size of the country. That expansion often came at a cost for specific groups of people, especially Native Americans and former enslaved African Americans who had escaped to the borderlands. But for the United States of America, expansion would have largely positive consequences, leading to the growth of the American economy, providing many American citizens with affordable land, and contributing to the United States’ emergence as one of the preeminent powers in the Western Hemisphere.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.