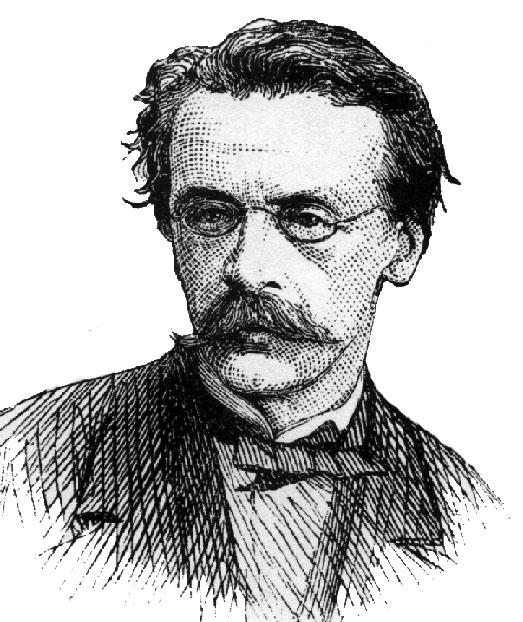

John Louis O’Sullivan, a popular editor and columnist, articulated the long-standing American belief in the God-given mission of the United States to lead the world in the peaceful transition to democracy. In a little-read essay printed in The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, O’Sullivan outlined the importance of annexing Texas to the United States: “Why, were other reasoning wanting, in favor of now elevating this question of the reception of Texas into the Union, out of the lower region of our past party dissensions, up to its proper level of a high and broad nationality, it surely is to be found, found abundantly, in the manner in which other nations have undertaken to intrude themselves into it, between us and the proper parties to the case, in a spirit of hostile interference against us, for the avowed object of thwarting our policy and hampering our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” O’Sullivan and many others viewed expansion as necessary to achieve America’s destiny and to protect American interests. The quasi-religious call to spread democracy coupled with the reality of thousands of settlers pressing westward. Manifest destiny was grounded in the belief that a democratic, agrarian republic would save the world.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

“Manifest Destiny”

Although called into name in 1845, manifest destiny was a widely held but vaguely defined belief that dated back to the founding of the nation. First, many Americans believed that the strength of American values and institutions justified moral claims to hemispheric leadership. Second, the lands on the North American continent west of the Mississippi River (and later into the Caribbean) were destined for American-led political and agricultural improvement. Third, God and the Constitution ordained an irrepressible destiny to accomplish redemption and democratization throughout the world. All three of these claims pushed many Americans, whether they uttered the words ‘manifest destiny’ or not, to actively seek the expansion the democracy. These beliefs and the resulting actions were often disastrous to anyone in the way of American expansion. The new religion of American democracy spread on the feet and in the wagons of those who moved west, imbued with the hope that their success would be the nation’s success.

The Young America movement, strongest among members of the Democratic Party but spanning the political spectrum, downplayed divisions over slavery and ethnicity by embracing national unity and emphasizing American exceptionalism, territorial expansion, democratic participation, and economic interdependence. Poet Ralph Waldo Emerson captured the political outlook of this new generation in a speech he delivered in 1844 entitled “The Young American”: “In every age of the world, there has been a leading nation, one of a more generous sentiment, whose eminent citizens were willing to stand for the interests of general justice and humanity, at the risk of being called, by the men of the moment, chimerical and fantastic. Which should be that nation but these States? Which should lead that movement, if not New England? Who should lead the leaders, but the Young American?”

The conquest of new territories west of the Appalachian Mountains had political repercussions back east, and inflamed sectional tensions over slavery. The precarious balance of power in Congress between the slaveholding South and the abolitionist North led to a series of compromises. The Wilmot Proviso, for instance, was an amendment asserting that the Mexican-American War had not been fought for the purpose of expanding slavery, and stipulated that slavery would never exist in the territories acquired from Mexico in the war. For obvious reasons, the slaveholding South opposed the proviso, and the struggle over the issue of slavery in the newly acquired territories was one of the major signposts on the road to the Civil War.

Many Americans, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, disapproved of aggressive expansion. For opponents of manifest destiny, the lofty rhetoric of the Young Americans was nothing other than a kind of imperialism that the American Revolution was supposed to have repudiated. Many members of the Whig Party (and later the Republican Party) argued that the United States’ mission was to lead by example, not by conquest. Abraham Lincoln summed up this criticism with a fair amount of sarcasm during a speech in 1859: “He (the Young American) owns a large part of the world, by right of possessing it; and all the rest by right of wanting it, and intending to have it…Young America had ‘a pleasing hope — a fond desire — a longing after’ territory. He has a great passion — a perfect rage — for the ‘new’; particularly new men for office, and the new earth mentioned in the revelations, in which, being no more sea, there must be about three times as much land as in the present. He is a great friend of humanity; and his desire for land is not selfish, but merely an impulse to extend the area of freedom. He is very anxious to fight for the liberation of enslaved nations and colonies, provided, always, they have land…As to those who have no land, and would be glad of help from any quarter, he considers they can afford to wait a few hundred years longer. In knowledge he is particularly rich. He knows all that can possibly be known; inclines to believe in spiritual trappings, and is the unquestioned inventor of ‘Manifest Destiny’.” But Lincoln and other anti-expansionists would struggle to win popular opinion. The nation, fueled by the principles of manifest destiny, would continue westward. Along the way, Americans battled both native peoples and foreign nations, claiming territory to the very edges of the continent. But westward expansion did not come without a cost. It exacerbated the slavery question, pushed Americans toward civil war, and, ultimately, threatened the very mission of American democracy it was designed to aid.

Source: Joshua Beatty et al., “Manifest Destiny,” Joshua Beatty and Gregg Lightfoot, eds., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com and Dr. Michelle Getchell, “Manifest Destiny,” https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-us-history/period-4/apush-age-of-jackson/a/manifest-destiny.

“Manifest Destiny” – Video

“Manifest Destiny”

Matthew Pinsker, “Sound Smart: Manifest Destiny,” History.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHemd90ZdsU

Summary

“Do not lounge in the cities!” commanded publisher Horace Greeley in 1841, “There is room and health in the country, away from the crowds of idlers and imbeciles. Go west, before you are fitted for no life but that of the factory.” The New York Tribune and numerous other publications argued that American exceptionalism required the United States to benevolently conquer the continent as the prime means of spreading American capitalism and American democracy, and the phrase “Go west young man!” became an oft-referenced platitude by the middle of the 19th century. Thousands of Americans would move west to find their fortunes in the 19th century, but not all Americans who moved west were successful. Harsh conditions, conflicts with Native Americans, and limited access to the industry and markets of the eastern seaboard, especially in the first half of the 19th century, meant that migrating west could be a difficult, isolating experience.

The concept of “Manifest Destiny” was never universally accepted, and many Americans asserted that the United States should lead by example, and not pursue a policy of aggressive territorial expansion. As the nation expanded westward, the conflicts that had already taken root back east, also migrated across the country. Most notably, new territories became fierce sites of conflict over the expansion of slavery and the removal of Native American peoples. Although America was not destined to expand across North America, the United States did expand significantly over the course of the 19th century. Ultimately, the concept of “Manifest Destiny” played a large role in justifying and legitimizing that expansion.