Few times in U.S. History have been as turbulent and transformative as the Civil War and the twelve

years that followed. Between 1865 and 1877, one president was murdered and another impeached. The Constitution underwent major revision with the addition of three amendments. The effort to impose Union control and create equality in the defeated South ignited a fierce backlash as various terrorist and vigilante, most notably the Ku Klux Klan, battled to maintain a pre–Civil War society in which whites held complete power. These groups unleashed a wave of violence, including lynching and arson, aimed at freed blacks and their white supporters. Historians refer to this era as Reconstruction, when an effort to remake the South faltered and ultimately failed.

The South, which had experienced catastrophic losses during the conflict, was reduced to political dependence and economic destitution. This humiliating condition led many southern whites to vigorously contest Union efforts to transform the South’s racial, economic, and social landscape.

Supporters of equality grew increasingly dismayed at Reconstruction’s failure to undo the old system, which further compounded the staggering regional and racial inequalities in the United States.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

A Plan to Reconstruct the Nation

By the spring of 1865, it had become clear to both sides that the Confederacy could not last much longer. Most of its major cities, ports, and industrial centers—Atlanta, Savannah, Charleston, Columbia, Mobile, New Orleans, and Memphis—had been captured. In April 1865, Lee had abandoned both Petersburg and Richmond. His goal in doing so was to unite his depleted army with Confederate forces commanded by General Johnston. Grant effectively cut him off. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. By that time, he had fewer than 35,000 soldiers, while Grant had some 100,000. Meanwhile, Sherman’s army proceeded to North Carolina, where General Johnston surrendered on April 19, 1865. The Civil War had come to an end. The war had cost the lives of more than 600,000 soldiers. Many more had been wounded. Thousands of women were left widowed. Children were left without fathers, and many parents were deprived of a source of support in their old age. In some areas, where local volunteer units had marched off to battle, never to return, an entire generation of young women was left without marriage partners. Millions of dollars’ worth of property had been destroyed, and towns and cities were laid to waste. With the conflict finally over, the very difficult work of reconciling North and South and reestablishing the United States lay ahead.

The end of the Civil War saw the beginning of the Reconstruction era, when former rebel Southern states were integrated back into the Union. President Lincoln moved quickly to achieve the war’s ultimate goal: reunification of the country. He proposed a generous and non-punitive plan to return the former Confederate states speedily to the United States, but some Republicans in Congress protested, considering the president’s plan too lenient to the rebel states that had torn the country apart. The greatest flaw of Lincoln’s plan, according to this view, was that it appeared to forgive traitors instead of guaranteeing civil rights to former slaves. President Lincoln oversaw the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but he did not live to see its ratification.

From the outset of the rebellion in 1861, Lincoln’s overriding goal had been to bring the Southern states quickly back into the fold in order to restore the Union. In early December 1863, the president began the process of reunification by unveiling a three-part proposal known as the ten percent plan that outlined how the states would return. The ten percent plan gave a general pardon to all Southerners except high-ranking Confederate government and military leaders; required 10 percent of the 1860 voting population in the former rebel states to take a binding oath of future allegiance to the United States and the emancipation of slaves; and declared that once those voters took those oaths, the restored Confederate states would draft new state constitutions.

Lincoln hoped that the leniency of the plan—90 percent of the 1860 voters did not have to swear allegiance to the Union or to emancipation—would bring about a quick and long-anticipated resolution and make emancipation more acceptable everywhere. This approach appealed to some in the moderate wing of the Republican Party, which wanted to put the nation on a speedy course toward reconciliation. However, the proposal instantly drew fire from a larger faction of Republicans in Congress who did not want to deal moderately with the South. These members of Congress, known as Radical Republicans, wanted to remake the South and punish the rebels. Radical Republicans insisted on harsh terms for the defeated Confederacy and protection for former slaves, going far beyond what the president proposed.

In February 1864, two of the Radical Republicans, Ohio senator Benjamin Wade and Maryland representative Henry Winter Davis, answered Lincoln with a proposal of their own. Among other stipulations, the Wade-Davis Bill called for a majority of voters and government officials in Confederate states to take an oath, called the Ironclad Oath, swearing that they had never supported the Confederacy or made war against the United States. Those who could not or would not take the oath would be unable to take part in the future political life of the South. Congress assented to the Wade-Davis Bill, and it went to Lincoln for his signature. The president refused to sign, using the pocket veto (that is, taking no action) to kill the bill. Lincoln understood that no Southern state would have met the criteria of the Wade-Davis Bill, and its passage would simply have delayed the reconstruction of the South.

Despite the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the legal status of slaves and the institution of slavery remained unresolved. To deal with the remaining uncertainties, the Republican Party made the abolition of slavery a top priority by including the issue in its 1864 party platform. The platform read: “That as slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength of this Rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of Republican Government, justice and the National safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the Republic; and that, while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the Government, in its own defense, has aimed a deathblow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of Slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.” The platform left no doubt about the intention to abolish slavery.

The president, along with the Radical Republicans, made good on this campaign promise in 1864 and 1865. A proposed constitutional amendment passed the Senate in April 1864, and the House of Representatives concurred in January 1865. The amendment then made its way to the states, where it swiftly gained the necessary support, including in the South. In December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and added to the Constitution. The first amendment added to the Constitution since 1804, it overturned a centuries-old practice by permanently abolishing slavery.

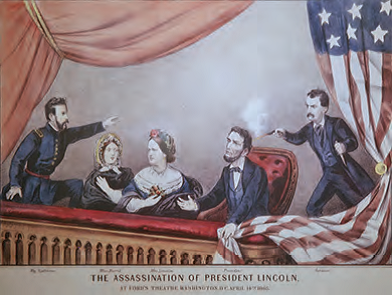

President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. On April 14, 1865, the Confederate supporter and well-known actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln while he was attending a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theater in Washington. The president died the next day. Booth had steadfastly defended the Confederacy and white supremacy, and his act was part of a larger conspiracy to eliminate the heads of the Union government and keep the Confederate fight going. One of Booth’s associates stabbed and wounded Secretary of State William Seward the night of the assassination. Another associate abandoned the planned assassination of Vice President Andrew Johnson at the last moment. Although Booth initially escaped capture, Union troops shot and killed him on April 26, 1865, in a Maryland barn. Eight other conspirators were convicted by a military tribunal for participating in the conspiracy, and four were hanged. Lincoln’s death earned him immediate martyrdom, and hysteria spread throughout the North. To many Northerners, the assassination suggested an even greater conspiracy than what was revealed, masterminded by the unrepentant leaders of the defeated Confederacy. Militant Republicans would use and exploit this fear relentlessly in the ensuing months.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

A Plan to Reconstruct the Nation

Foner, E. Lincoln, Louisiana, and Reconstruction: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1865. (2015, February 23). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IejvG-fozRU

Foner, E. The End of the War: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1865. (2015, February 23). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7cc9l5KZRLI

Summary

By 1865, it was clear that the Confederacy was on the brink of defeat. Surrounded and trapped by General Grant’s Army, General Robert E. Lee agreed to surrender. Lee’s surrender effectively brought an end to the Civil War. Even before the war had ended, President Lincoln had established a policy for Reconstruction. Lincoln was eager to reunify the nation, which had always been his primary goal. Under Lincoln’s Reconstruction play, southern states would be able to quickly rejoin the union. To rejoin the Union, ten percent of a state’s population had to pledge loyalty to the federal government. Further, in order to rejoin the Union, each southern state had to formally abolish slavery. Many Radical Republicans in Congress believed that Lincoln’s plan for Reconstruction was too lenient towards the rebels who had betrayed the nation. In 1865, President Abraham Lincoln was shot and killed by a southern actor named John Wilkes Booth while attending a play at Ford’s Theatre.