In this learning activity, you will learn about the causes of the American Revolution. A number of issues contributed to rising tensions between the American colonists and the British government from 1763 to 1776. The rising tensions began at the conclusion of the French and Indian War. At the end of this war, the British government was massively in-debt. The British government raised taxes on American colonists in an effort to pay for this war debt. American colonists resented and opposed the rise in taxation. The dispute over taxation led to a number of protests by the American colonists, culminating in the Boston Tea Party. The British government asserted that they had every right to tax their colonies. Many American colonists believed it was unfair to for Parliament to levy taxes on the American colonies, when the colonists had no representation in Parliament. The British government was outraged by the Boston Tea Party and responded by closing the port of Boston. Tensions quickly escalated.

The Origins of the American Revolution

Causes of the American Revolution

Most immediately, the American Revolution resulted directly from attempts to reform the British Empire after the Seven Years’ War. The Seven Years’ War culminated nearly a half-century of war between Europe’s imperial powers. It was truly a world war, fought between multiple empires on multiple continents. At its conclusion, the British Empire had never been larger. Britain now controlled the North American continent east of the Mississippi River, including French Canada . . . But the realities and responsibilities of the post-war empire were daunting. War (let alone victory) on such a scale was costly. Britain doubled the national debt to 13.5 times its annual revenue. Britain faced significant new costs required to secure and defend its far-flung empire, especially the western frontiers of the North American colonies. These factors led Britain in the 1760s to attempt to consolidate control over its North American colonies, which, in turn, led to resistance.

King George III took the crown in 1760 and brought Tories into his Ministry after three decades of Whig rule. They represented an authoritarian vision of empire where colonies would be subordinate. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was Britain’s first major postwar imperial action concerning North America. The King forbade settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains in an attempt to limit costly wars with Native Americans. Colonists, however, protested and demanded access to the territory for which they had fought alongside the British.

In 1764, Parliament passed two more reforms. The Sugar Act sought to combat widespread smuggling of molasses in New England by cutting the duty in half but increasing enforcement. Also, smugglers would be tried by vice-admiralty courts and not juries. Parliament also passed the Currency Act, which restricted colonies from producing paper money. Hard money, like gold and silver coins, was scarce in the colonies. The lack of currency impeded the colonies’ increasingly sophisticated transatlantic economies, but it was especially damaging in 1764 because a postwar recession had already begun. Between the restrictions of the Proclamation of 1763, the Currency Act, and the Sugar Act’s canceling of trials-by-jury for smugglers, some colonists began to fear a pattern of increased taxation and restricted liberties.

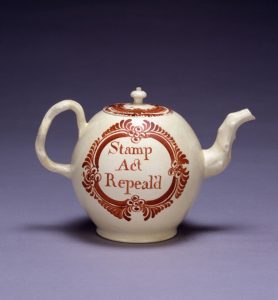

In March 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. The act required many documents be printed on paper that had been stamped to show the duty had been paid, including newspapers, pamphlets, diplomas, legal documents, and even playing cards. The Sugar Act of 1764 was an attempt to get merchants to pay an already-existing duty, but the Stamp Act created a new, direct (or “internal”) tax. Parliament had never before directly taxed the colonists. Instead, colonies contributed to the empire through the payment of indirect, “external” taxes, such as customs duties . . . Also, unlike the Sugar Act, which primarily affected merchants, the Stamp Act directly affected numerous groups throughout colonial society, including printers, lawyers, college graduates, and even sailors who played cards. This led, in part, to broader, more popular resistance.

Resistance to the Stamp Act took three forms, distinguished largely by class: legislative resistance by elites, economic resistance by merchants, and popular protest by common colonists. Colonial elites responded with legislative resistance initially by passing resolutions in their assemblies. The most famous of the anti-Stamp Act resolutions were the “Virginia Resolves,” passed by the House of Burgesses on May 30, 1765, which declared that the colonists were entitled to “all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities . . . possessed by the people of Great Britain.” . . . [A Stamp Act Congress was convened in New York City in October 1765.]

Nine colonies sent delegates, including Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Thomas Hutchinson, Philip Livingston, and James Otis. The Stamp Act Congress issued a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances,” which, like the Virginia Resolves, declared allegiance to the King and “all due subordination” to Parliament, but also reasserted the idea that colonists were entitled to the same rights as native Britons. Those rights included trial by jury, which had been abridged by the Sugar Act, and the right to only be taxed by their own elected representatives . . . Because the colonies did not elect members to Parliament, they believed that they were not represented and could not be taxed by that body. In response, Parliament and the Ministry argued that the colonists were “virtually represented,” just like the residents of those boroughs or counties in England that did not elect members to Parliament. However, the colonists rejected the notion of virtual representation, with one pamphleteer calling it a “monstrous idea.”

The second type of resistance to the Stamp Act was economic. While the Stamp Act Congress deliberated, merchants in major port cities were preparing non-importation agreements, hoping that their refusal to import British goods would lead British merchants to lobby for the repeal of the Stamp Act. In New York City, “upwards of two hundred principal merchants” agreed not to import, sell, or buy “any goods, wares, or merchandises” from Great Britain. In Philadelphia, merchants gathered at “a general meeting” to agree that “they would not Import any Goods from Great-Britain until the Stamp-Act was Repealed.” The plan worked. By January 1766, London merchants sent a letter to Parliament arguing that they had been “reduced to the necessity of pending ruin” by the Stamp Act and the subsequent boycotts.

The third, and perhaps, most crucial type of resistance was popular protest. Violent riots broke out in Boston. Crowds burned the appointed stamp distributor for Massachusetts, Andrew Oliver, in effigy and pulled a building he owned “down to the Ground in five minutes.” Oliver resigned the position the next day. The following week, a crowd also set upon the home of his brother-in-law, Lt. Gov. Thomas Hutchinson, who had publicly argued for submission to the stamp tax. Before the evening was over, much of Hutchinson’s home and belongings had been destroyed. Popular violence and intimidation spread quickly throughout the colonies.

By November 16, all of the original twelve stamp distributors had resigned, and by 1766, groups who called themselves the “Sons of Liberty” were formed in most of the colonies to direct and organize further popular resistance. These tactics had the dual effect of sending a message to Parliament and discouraging colonists from accepting appointments as stamp collectors. With no one to distribute the stamps, the Act became unenforceable.

Pressure on Parliament grew until, in February of 1766, they repealed the Stamp Act. But to save face and to try to avoid this kind of problem in the future, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, asserting that Parliament had the “full power and authority to make laws . . . to bind the colonies and people of America . . . in all cases whatsoever.” However, colonists were too busy celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act to take much notice of the Declaratory Act. In New York City, the inhabitants raised a huge lead statue of King George III in honor of the Stamp Act’s repeal. It could be argued that there was no moment at which colonists felt more proud to be members of the free British Empire than 1766. But Britain still needed revenue from the colonies.

The colonies had resisted the implementation of direct taxes, but the Declaratory Act reserved Parliament’s right to impose them. And, in the colonists’ dispatches to Parliament and in numerous pamphlets, they had explicitly acknowledged the right of Parliament to regulate colonial trade. So Britain’s next attempt to draw revenues from the colonies, the Townshend Acts, were passed in June 1767, creating new customs duties on common items, like lead, glass, paint, and tea, instead of direct taxes. The Acts also created and strengthened formal mechanisms to enforce compliance, including a new American Board of Customs Commissioners and more vice-admiralty courts to try smugglers. Revenues from customs seizures would be used to pay customs officers and other royal officials, including the governors, thereby incentivizing them to convict offenders. These acts increased the presence of the British government in the colonies and circumscribed the authority of the colonial assemblies, since paying the governor’s salary had long given the assemblies significant power over them. Unsurprisingly, colonists, once again, resisted.

Even though these were duties, many colonial resistance authors still referred to them as “taxes,” because they were designed primarily to extract revenues from the colonies not to regulate trade . . . Hence, many authors asked: once the colonists assented to a tax in any form, what would stop the British from imposing ever more and greater taxes on the colonists?

New forms of resistance emerged in which elite, middling, and working class colonists participated together. Merchants re-instituted non-importation agreements, and common colonists agreed not to consume these same products. Lists were circulated with signatories promising not to buy any British goods. These lists were often published in newspapers, bestowing recognition on those who had signed and led to pressure on those who had not.

Women, too, became involved to an unprecedented degree in resistance to the Townshend Acts. They circulated subscription lists and gathered signatures. The first political commentaries in newspapers written by women appeared. Also, without new imports of British clothes, colonists took to wearing simple, homespun clothing. Spinning clubs were formed, in which local women would gather at one their homes and spin cloth for homespun clothing for their families and even for the community.

Homespun clothing quickly became a marker of one’s virtue and patriotism, and women were an important part of this cultural shift. At the same time, British goods and luxuries previously desired now became symbols of tyranny. Non-importation, and especially, non-consumption agreements changed colonists’ cultural relationship with the mother country. Committees of Inspection monitored merchants and residents to make sure that no one broke the agreements. Offenders could expect to be shamed by having their names and offenses published in the newspaper and in broadsides.

Non-importation and non-consumption helped forge colonial unity. Colonies formed Committees of Correspondence to keep each other informed of the resistance efforts throughout the colonies. Newspapers reprinted exploits of resistance, giving colonists a sense that they were part of a broader political community. The best example of this new “continental conversation” came in the wake of the “Boston Massacre.” Britain sent regiments to Boston in 1768 to help enforce the new acts and quell the resistance. On the evening of March 5, 1770, a crowd gathered outside the Custom House and began hurling insults, snowballs, and perhaps more at the young sentry. When a small number of soldiers came to the sentry’s aid, the crowd grew increasingly hostile until the soldiers fired. After the smoke cleared, five Bostonians were dead, including one of the ringleaders, Crispus Attucks, a former slave turned free dockworker. The soldiers were tried in Boston and won acquittal, thanks, in part, to their defense attorney, John Adams. News of the “Boston Massacre” spread quickly through the new resistance communication networks, aided by a famous engraving initially circulated by Paul Revere, which depicted bloodthirsty British soldiers with grins on their faces firing into a peaceful crowd. The engraving was quickly circulated and reprinted throughout the colonies, generating sympathy for Boston and anger with Britain.

This is an image depicting the Boston Massacre made by Paul revere. In the image a group of seven British soldiers wearing Redcoats fire into a crowd of colonists. A British officers directs the soldiers to open fire. Colonists are depicted in civilian clothing. Colonists are bleeding on the ground from gunshot wounds.

Boston Massacre by Paul Revere. The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

In April of 1773, Parliament passed two acts to aid the failing East India Company, which had fallen behind in the annual payments it owed Britain. But the Company was not only drowning in debt; it was also drowning in tea, with almost 15 million pounds of it in stored in warehouses from India to England. So, in 1773, the Parliament passed the Regulating Act, which effectively put the troubled company under government control. It then passed the Tea Act, which would allow the Company to sell its tea in the colonies directly and without the usual import duties. This would greatly lower the cost of tea for colonists, but, again, they resisted.

Merchants resisted because they deplored the East India Company’s monopoly status that made it harder for them to compete. But, like the Sugar Act, it only affected a small, specific group of people. The widespread support for resisting the Tea Act had more to do with principles. By buying the tea, even though it was cheaper, colonists would be paying the duty and thereby implicitly acknowledging Parliament’s right to tax them . . .

The Tea Act stipulated that the duty had to be paid when the ship unloaded. Newspaper essays and letters throughout the summer of 1773 in the major port cities debated what to do upon the ships’ arrival. In November, the Boston Sons of Liberty, led by Samuel Adams and John Hancock, resolved to “prevent the landing and sale of the [tea], and the payment of any duty thereon” and to do so “at the risk of their lives and property. The meeting appointed men to guard the wharfs and make sure the tea remained on the ships until they returned to London. This worked and the tea did not reach the shore, but by December 16, the ships were still there. Hence, another town meeting was held at the Old South Meeting House, at the end of which dozens of men disguised as Mohawk Indians made their way to the wharf. The Boston Gazette reported what happened next:

But, behold what followed! A number of brave & resolute men, determined to do all in their power to save their country from the ruin which their enemies had plotted, in less than four hours, emptied every chest of tea on board the three ships . . . amounting to 342 chests, into the sea ! ! without the least damage done to the ships or any other property.

As word spread throughout the colonies, patriots were emboldened to do the same to the tea sitting in their harbors. Tea was either dumped or seized in Charleston, Philadelphia, and New York, with numerous other smaller “tea parties” taking place throughout 1774.

Popular protest spread across the continent and down through all levels of colonial society. Fifty-one women in Edenton, North Carolina, for example, signed an agreement––published in numerous newspapers––in which they promised “to do every Thing as far as lies in our Power” to support the boycotts. The ladies of Edenton were not alone in their desire to support the war effort by what means they could. Women across the thirteen colonies could most readily express their political sentiments as consumers and producers. Because women were often making decisions regarding which household items to purchase, their participation in consumer boycotts held particular weight. Some women also took to the streets as part of more unruly mob actions, participating in grain riots, raids on the offices of royal officials, and demonstrations against the impressment of men into naval service. The agitation of so many helped elicit responses from both Britain and the colonial elites.

Britain’s response was swift. The following spring, Parliament passed four acts known collectively, by the British, as the “Coercive Acts.” Colonists, however, referred to them as the “Intolerable Acts.” First, the Boston Port Act shut down the harbor and cut off all trade to and from the city. The Massachusetts Government Act put the colonial government entirely under British control, dissolving the assembly and restricting town meetings. The Administration of Justice Act allowed any royal official accused of a crime to be tried in Britain rather than by Massachusetts courts and juries. Finally, the Quartering Act, passed for all colonies, allowed the British army to quarter newly arrived soldiers in colonists’ homes. Boston had been deemed in open rebellion, and the King, his Ministry, and Parliament acted decisively to end the rebellion.

The Ministry, however, did not anticipate the other colonies coming to the aid of Massachusetts. Colonists collected food to send to Boston. Virginia’s House of Burgesses called for a day of prayer and fasting to show their support. Rather than isolating Massachusetts, as the Ministry had hoped, the Coercive Acts fostered the sense of shared identity created over the previous decade. After all, if the Ministry and Parliament could dissolve Massachusetts’ government, nothing could stop them from doing the same to any of her sister colonies. In Massachusetts, patriots created the “Provincial Congress,” and, throughout 1774, they seized control of local and county governments and courts. In New York, citizens elected committees to direct the colonies’ response to the Coercive Acts . . . By early 1774, Committees of Correspondence and/or extra-legal assemblies were established in all of the colonies except Georgia. And throughout the year, they followed Massachusetts’ example by seizing the powers of the royal governments.

Committees of Correspondence agreed to send delegates to a Continental Congress to coordinate an inter-colonial response. The First Continental Congress convened on September 5, 1774. Over the next six weeks, elite delegates from every colony but Georgia issued a number of documents, including a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances.” This document repeated the arguments that colonists had been making since 1765: colonists retained all the rights of native Britons, including the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives as well as the right to trial-by-jury.

Most importantly, the Congress issued a document known as the “Continental Association.” The Association declared that “the present unhappy situation of our affairs is occasioned by a ruinous system of colony administration adopted by the British Ministry about the year 1763, evidently calculated for enslaving these Colonies, and, with them, the British Empire.” The Association recommended “that a committee be chosen in every county, city, and town … whose business it shall be attentively to observe the conduct of all persons touching this association.” These Committees of Inspection would consist largely of common colonists. They were effectively deputized to police their communities and instructed to publish the names of anyone who violated the Association so they “may be publicly known, and universally condemned as the enemies of American liberty.” The delegates also agreed to a continental non-importation, non-consumption, and non-exportation agreement and to “wholly discontinue the slave trade.” In all, the Continental Association was perhaps the most radical document of the period. It sought to unite and direct twelve revolutionary governments, establish economic and moral policies, and empower common colonists by giving them an important and unprecedented degree of on-the-ground political power.

But not all colonists were patriots. Indeed, many remained faithful to the King and Parliament, while a good number took a neutral stance. As the situation intensified throughout 1774 and early 1775, factions emerged within the resistance movements in many colonies. Elite merchants who traded primarily with Britain, Anglican clergy, and colonists holding royal offices depended on and received privileges directly from their relationship with Britain. Initially, they sought to exert a moderating influence on the resistance committees but, following the Association, a number of these colonists began to worry that the resistance was too radical and aimed at independence. They, like most colonists in this period, still expected a peaceful conciliation with Britain, and grew increasingly suspicious of the resistance movement.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The Origins of the American Revolution

Causes of the American Revolution

Pulley, P. American Revolution, Part I. (2014, September 23). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWHoxxZR9nw

Summary

A number or events contributed to the tension that culminated in the American Revolution. Economic tensions were the driving force behind the American Revolution. The British government viewed the American colonies as a source of revenue. Following the end of the French and Indian War, the British government attempted to extract revenue from the colonists to pay for their war debt. The American colonists believed that they had a right to self-government and possessed the same rights as English citizens. Taxation proved to be a fundamental cause of the American Revolution. The British government maintained that they had a right to levy taxes on the colonists without their consent, while the American colonists rejected this. Tensions became most intense in the city of Boston as a result of both the Boston “Massacre” and the Boston Tea Party.