From the sixteenth century through the early nineteenth century, over 10 million people were transported from West Africa to the Americas as slaves. After Europeans came into contact with Native Americans in 1492, much of the Native American population died as a result of disease. Europeans established colonies in the Americas and sought to profit through mining and agriculture. Europeans sought laborers to work on the plantations and mines of America. Europeans turned to African slaves. In the Atlantic Slave trade, Europeans merchants purchased human beings from West Africa in exchange for various European made goods. These Africans were loaded onto slave trading ships. In the “middle passage,” slaves crossed the Atlantic on these ships. The conditions on the ships were horrific. In the Americas, the slaves were exchanged with American merchants in exchange for a variety of agricultural goods. In the Americas, slaves were typically forced to work in harsh conditions on plantations and in mines.

Atlantic Slave Trade

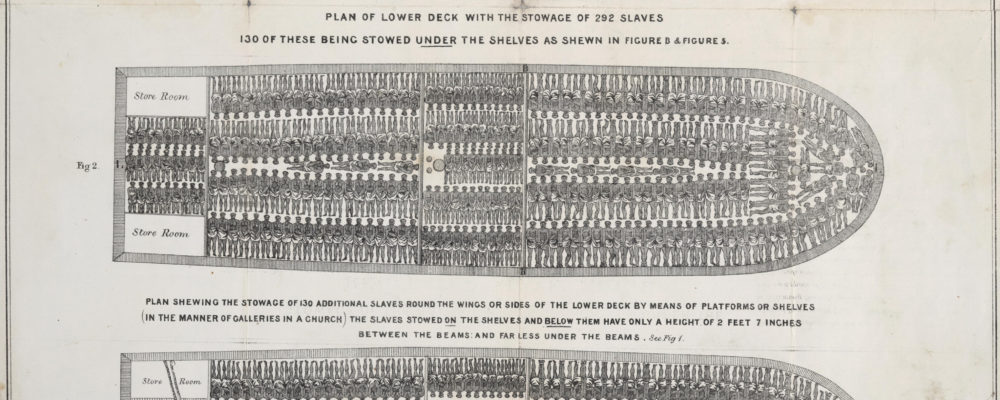

Native American slaves died quickly, mostly from disease. The demands of growing plantation economies required a more reliable labor force, and the transatlantic slave trade provided such a workforce. European slavers transported millions of Africans across the ocean in a terrifying journey known as the Middle Passage. Writing at the end of the eighteenth century, Olaudah Equiano recalled the fearsomeness of the crew, the filth and gloom of the hold, the inadequate provisions allotted for the captives, and the desperation that drove some slaves to suicide. In the same time period, Alexander Falconbridge, a slave ship surgeon, described the sufferings of slaves from shipboard infections and close quarters in the hold. Dysentery, known as “the bloody flux,” left captives lying in pools of excrement. Chained in small spaces in the hold, slaves could lose so much skin and flesh from chafing against metal and timber that their bones protruded. Other sources detailed rapes, whippings, and diseases like smallpox and conjunctivitis aboard slave ships.

“Middle” had various meanings in the Atlantic slave trade. For the captains and crews of slave ships, the Middle Passage was one leg in the maritime trade in sugar and other semi-finished American goods, manufactured European commodities, and African slaves. For the enslaved Africans, the Middle Passage was the middle leg of three distinct journeys from Africa to the Americas. First was an overland journey in Africa to a coastal slave-trading factory, often a trek of hundreds of miles. Second—and middle—was an oceanic trip lasting from one to six months in a slaver. Third was acculturation (known as “seasoning”) and transportation to the American mine, plantation, or other location where new slaves were forced to labor.

The impact of the Middle Passage on the cultures of the Americas remains evident today. Many foods associated with Africans, such as cassava, were originally imported to West Africa as part of the slave trade and were then adopted by African cooks before being brought to the Americas, where they are still consumed. West African rhythms and melodies live in new forms today in music as varied as religious spirituals and synthesized drumbeats. African influences appear in the basket making and language of the Gullah people on the Carolina Coastal Islands.

Recent estimates count between 11 and 12 million Africans forced across the Atlantic between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, with about 2 million deaths at sea as well as an additional several million dying in the trade’s overland African leg or during seasoning. Conditions in all three legs of the slave trade were horrible, but the first abolitionists focused especially on the abuses of the Middle Passage.

Southern European trading empires like the Catalans and Aragonese were brought into contact with a Levantine commerce in sugar and slaves in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Europeans made the first steps toward an Atlantic slave trade in the 1440s when Portuguese sailors landed in West Africa in search of gold, spices, and allies against the Muslims who dominated Mediterranean trade. Beginning in the 1440s, ship captains carried African slaves to Portugal. These Africans were valued primarily as domestic servants, as peasants provided the primary agricultural labor force in Western Europe. European expansion into the Americas introduced both settlers and European authorities to a new situation—an abundance of land and a scarcity of labor. Portuguese, Dutch, and English ships became the conduits for Africans forced to America. The western coast of Africa, the Gulf of Guinea, and the west-central coast were the sources of African captives. Wars of expansion and raiding parties produced captives who could be sold in coastal factories. African slave traders bartered for European finished goods such as beads, cloth, rum, firearms, and metal wares.

Slavers often landed in the British West Indies, where slaves were seasoned in places like Barbados. Charleston, South Carolina, became the leading entry point for the slave trade on the mainland. The founding of Charleston (“Charles Town” until the 1780s) in 1670 was viewed as a serious threat by the Spanish in neighboring Florida, who began construction of Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine as a response. In 1693 the Spanish king issued the Decree of Sanctuary, which granted freedom to slaves fleeing the English colonies if they converted to Catholicism and swore an oath of loyalty to Spain. The presence of Africans who bore arms and served in the Spanish militia testifies to the different conceptions of race among the English and Spanish in America.

About 450,000 Africans landed in British North America, a relatively small portion of the 11 to 12 million victims of the trade. As a proportion of the enslaved population, there were more enslaved women in North America than in other colonial slave populations. Enslaved African women also bore more children than their counterparts in the Caribbean or South America, facilitating the natural reproduction of slaves on the North American continent. A 1662 Virginia law stated that an enslaved woman’s children inherited the “condition” of their mother; other colonies soon passed similar statutes. This economic strategy on the part of planters created a legal system in which all children born to slave women would be slaves for life, whether the father was white or black, enslaved or free.

Most fundamentally, the emergence of modern notions of race was closely related to the colonization of the Americas and the slave trade. African slave traders lacked a firm category of race that might have led them to think that they were selling their own people, in much the same way that Native Americans did not view other Indian groups as part of the same “race.” Similarly, most English citizens felt no racial identification with the Irish or the even the Welsh. The modern idea of race as an inherited physical difference (most often skin color) that is used to support systems of oppression was new in the early modern Atlantic world.

In the early years of slavery, especially in the South, the distinction between indentured servants and slaves was initially unclear. In 1643, however, a law was passed in Virginia that made African women “tithable.” This, in effect, associated African women’s work with difficult agricultural labor. There was no similar tax levied on white women; the law was an attempt to distinguish white from African women. The English ideal was to have enough hired hands and servants working on a farm so that wives and daughters did not have to partake in manual labor. Instead, white women were expected to labor in dairy sheds, small gardens, and kitchens. Of course, due to the labor shortage in early America, white women did participate in field labor. But this idealized gendered division of labor contributed to the English conceiving of themselves as better than other groups who did not divide labor in this fashion, including the West Africans arriving in slave ships to the colonies. For many white colonists, the association of a gendered division of labor with Englishness provided a further justification for the enslavement and subordination of Africans.

Ideas about the rule of the household were informed by legal and customary understandings of marriage and the home in England. A man was expected to hold “paternal dominion” over his household, which included his wife, children, servants, and slaves. In contrast, slaves were not legally masters of a household, and were therefore subject to the authority of the white master. Slave marriages were not recognized in colonial law. Some enslaved men and women married “abroad”; that is, they married individuals who were not owned by the same master and did not live on the same plantation. These husbands and wives had to travel miles at a time, typically only once a week on Sundays, to visit their spouses. Legal or religious authority did not protect these marriages, and masters could refuse to let their slaves visit a spouse, or even sell a slave to a new master hundreds of miles away from their spouse and children. Within the patriarchal and exploitative colonial environment, enslaved men and women struggled to establish families and communities.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

Atlantic Slave Trade – Video

Atlantic Slave Trade. (19 December 2012). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UvDDpa-6LLk

Summary

From the sixteenth century through the early nineteenth century, between 10 and 12 million people were transported from West Africa to the Americas as slaves. Portugal was the first nation to participate in the slave trade, but many other European nations soon followed. The conditions on the slave ships that carried slaves across the Atlantic were horrific. Slaves were chained below decks in extremely overcrowded and unsanitary conditions. Not surprisingly, given the conditions, many slaves died during the voyage. Most slaves were purchased by European merchants on the coast of West Africa. The Atlantic Slave Trade became was a central aspect of the global economy in the eighteenth century.