Between the 17th and 19th centuries, one of the central features of American history was expansion, and as the colonies that would eventually become the United States of America continued to expand, they repeatedly encroached upon Native American territory. The region between Native American territory and the colonies became known as the border lands, where Native Americans and colonists struggled to assert their control over each other, and where peaceful coexistence could quickly give way to violence. In this assignment, we will explore how tensions over borders shaped three key moments in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries: Bacon’s Rebellion, the Seven Years War, and the Louisiana Purchase.

Border Lands

Bacon’s Rebellion began, appropriately enough, with an argument over a pig. In the summer of 1675, a group of Doeg Indians visited Thomas Mathew on his plantation in northern Virginia to collect a debt that he owed them. When Mathew refused to pay, they took some of his pigs to settle the debt. This “theft” sparked a series of raids and counter-raids. The Susquehannock Indians were caught in the crossfire when the militia mistook them for Doegs, leaving fourteen dead. A similar pattern of escalating violence then repeated: the Susquehannocks retaliated by killing colonists in Virginia and Maryland, and the English marshaled their forces and laid siege to the Susquehannocks. The conflict became uglier after the militia executed a delegation of Susquehannock ambassadors under a flag of truce. A few parties of warriors intent on revenge launched raids along the frontier and killed dozens of English colonists.

The sudden and unpredictable violence of the Susquehannock War triggered a political crisis in Virginia. Panicked colonists fled en masse from the vulnerable frontiers, flooding into coastal communities and begging the government for help. But the cautious governor, Sir William Berkeley, did not send an army after the Susquehannocks. He worried that a full-scale war would inevitably drag other Indians into the conflict, turning allies into deadly enemies. Berkeley therefore insisted on a defensive strategy centered around a string of new fortifications to protect the frontier and strict instructions not to antagonize friendly Indians. It was a sound military policy but a public relations disaster. Terrified colonists condemned Berkeley. Building contracts for the forts went to Berkeley’s wealthy friends, who conveniently decided that their own plantations were the most strategically vital. Colonists denounced the government as a corrupt band of oligarchs more interested in lining their pockets than protecting the people.

By the spring of 1676, a small group of frontier colonists took matters into their own hands. Naming the charismatic young Nathaniel Bacon as their leader, these self-styled “volunteers” proclaimed that they took up arms in defense of their homes and families. They took pains to assure Berkeley that they intended no disloyalty, but Berkeley feared a coup and branded the volunteers as traitors. Berkeley finally mobilized an army—not to pursue Susquehannocks, but to crush the colonists’ rebellion. His drastic response catapulted a small band of anti-Indian vigilantes into full-fledged rebels whose survival necessitated bringing down the colonial government.

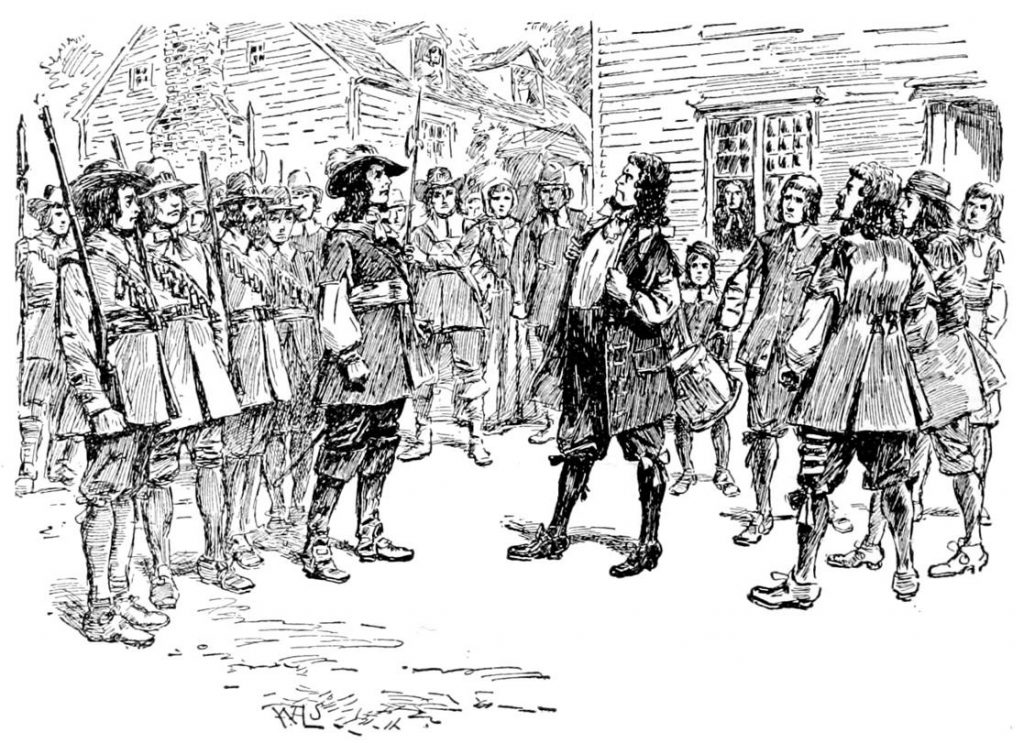

Bacon and the rebels stalked the Susquehannock as well as friendly Indians like the Pamunkeys and the Occaneechis. The rebels became convinced that there was a massive Indian conspiracy to destroy the English. Berkeley’s stubborn persistence in defending friendly Indians and destroying the Indian-fighting rebels led Bacon to accuse the governor of conspiring with a “powerful cabal” of elite planters and with “the protected and darling Indians” to slaughter his English enemies. In the early summer of 1676, Bacon’s neighbors elected him their burgess and sent him to Jamestown to confront Berkeley. Though the House of Burgesses enacted pro-rebel reforms like prohibiting the sale of arms to Indians and restoring suffrage rights to landless freemen, Bacon’s supporters remained unsatisfied. Berkeley soon had Bacon arrested and forced the rebel leader into the humiliating position of publicly begging forgiveness for his treason. Bacon swallowed this indignity, but turned the tables by gathering an army of followers and surrounding the State House, demanding that Berkeley name him the General of Virginia and bless his universal war against Indians. Instead, the 70-year old governor stepped onto the field in front of the crowd of angry men, unafraid, and called Bacon a traitor to his face. Then he tore open his shirt and dared Bacon to shoot him in the heart, if he was so intent on overthrowing his government. “Here!” he shouted before the crowd, “Shoot me, before God, it is a fair mark. Shoot!” When Bacon hesitated, Berkeley drew his sword and challenged the young man to a duel, knowing that Bacon could neither back down from a challenge without looking like a coward nor kill him without making himself into a villain. Instead, Bacon resorted to bluster and blasphemy. Threatening to slaughter the entire Assembly if necessary, he cursed, “God damn my blood, I came for a commission, and a commission I will have before I go.” Berkeley stood defiant, but the burgesses finally prevailed upon him to grant Bacon’s request. Virginia had its general, and Bacon had his war.

After this dramatic showdown in Jamestown, Bacon’s Rebellion quickly spiraled out of control. Berkeley slowly rebuilt his loyalist army, forcing Bacon to divert his attention to the coasts and away from the Indians. But most rebels were more interested in defending their homes and families than in fighting other Englishmen and deserted in droves at every rumor of Indian activity. In many places, the “rebellion” was less an organized military campaign than a collection of local grievances and personal rivalries. Both rebels and loyalists smelled the opportunities for plunder, seizing their rivals’ estates and confiscating their property. Everyone accused everyone else of treason, rebels and loyalists switched sides depending on which side was winning, and the whole Chesapeake disintegrated into a confused melee of secret plots and grandiose crusades, sordid vendettas and desperate gambits, with Indians and English alike struggling for supremacy and survival. The rebels steadily lost ground and ultimately suffered a crushing defeat. Bacon died of typhus in the autumn of 1676, and his successors surrendered to Berkeley in January 1677. Berkeley summarily tried and executed the rebel leadership in a succession of kangaroo courts-martial. Before long, however, the royal fleet arrived, bearing over 1,000 red-coated troops and a royal commission of investigation charged with restoring order to the colony. The commissioners replaced the governor and dispatched Berkeley to London, where he died in disgrace. The maintenance of order remained precarious for years afterward. The garrison of royal troops discouraged both incursion by hostile Indians and insurrection by discontented colonists, allowing the king to continue profiting from tobacco revenues. The end of armed resistance did not mean a resolution to the underlying tensions destabilizing colonial society. Indians inside Virginia remained an embattled minority and Indians outside Virginia remained a terrifying threat.

Source: Gregory Ablavsky et al., “British North America,” Daniel Johnson, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Border Lands – Video

Border Lands

Khan Academy. The Seven Years War

Khan Academy. The Seven Years War. Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/world-history/1600s-1800s/seven-years-war/v/the-seven-years-war-part-1

Summary

Thomas Jefferson’s rhetoric of equality contrasted harshly with the reality of a nation stratified along the lines of gender, class, race, and ethnicity. Diplomatic relations between Native Americans and local, state, and national governments offer a dramatic example of the dangers of those inequalities.

Americans pushed for more land in all their interactions with Native diplomats and leaders. But boundaries were only one source of tension. Trade, criminal jurisdiction, roads, the sale of liquor, and alliances were also key negotiating points. Despite their role in fighting on both sides, Native American negotiators were not included in the diplomatic negotiations that ended the Revolutionary War. Unsurprisingly, the final document omitted concessions for Native allies. Even as Native peoples proved vital trading partners, scouts, and allies against hostile nations, they were often condemned by white settlers and government officials as “savages.” White ridicule of indigenous practices and disregard for indigenous nations’ property rights and sovereignty prompted some indigenous peoples to turn away from white practices. Tensions and disagreements over borders and territory would inform American politics from the early colonial era until the late 19th century. As Bacon’s Rebellion, the Seven Years War, and the Louisiana Purchase all reveal, the borderlands were a recurring source of conflict in American life for almost its entire early history.

Source: Justin Clark et al., “The Early Republic,” Nathaniel C. Green, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com