In this learning activity, you will learn about the American Revolution. You will learn about the Declaration of Independence that was issued by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. The Declaration of Independence was drafted to provide a justification for the Revolution. The document asserts that the British government had become tyrannical and unjust. You will also learn about the major battles and turning points of the Revolutionary War including the Battle of Lexington, the Battle of Saratoga, and the Battle of Yorktown. In the opening years of the war, most battles took place in the Northeast in Massachusetts, New York, and New Jersey. In the latter years of the war, the fighting shifted to the American South. It is quite remarkable that the American colonists were able to defeat the greatest empire in the world to win their independence.

The American Revolution

The Declaration of Independence

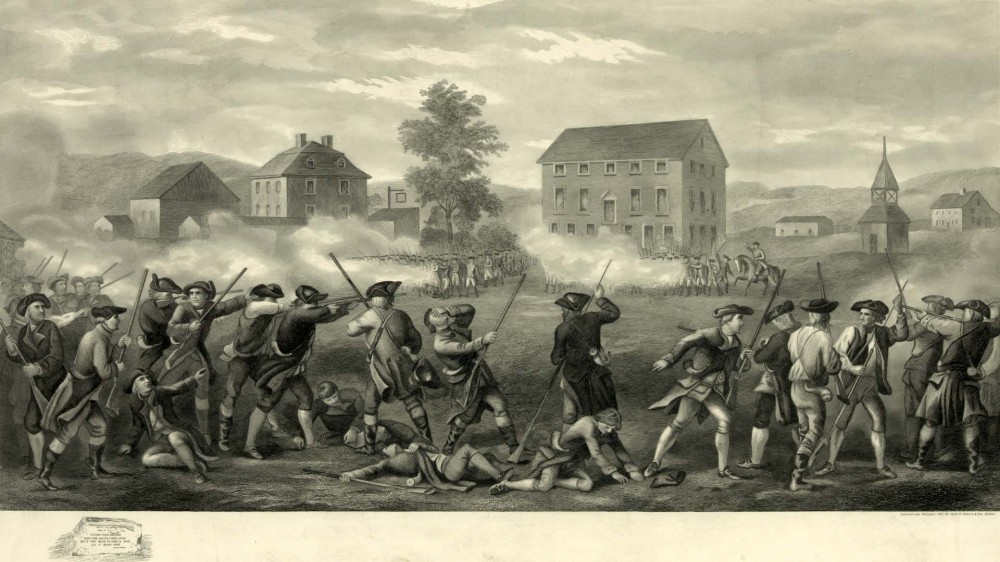

By the time the Continental Congress met in May 1775, war had already broken out in Massachusetts. On April 19, 1775, British regiments set out to seize local militias’ arms and powder stores in Lexington and Concord. The town militia met them at the Lexington Green. The British ordered the militia to disperse when someone fired, setting off a volley from the British. The battle continued all the way to the next town, Concord. News of the events at Lexington spread rapidly throughout the countryside. Militia members, known as “minutemen,” responded quickly and inflicted significant casualties on the British regiments as they chased them back to Boston. Approximately 20,000 colonial militiamen lay siege to Boston, effectively trapping the British. In June, the militia set up fortifications on Breed’s Hill overlooking the city. In the misnamed “Battle of Bunker Hill,” the British attempted to dislodge them from the position with a frontal assault, and, despite eventually taking the hill, they suffered severe casualties at the hands of the colonists.

While men in Boston fought and died, the Continental Congress struggled to organize a response. The radical Massachusetts delegates––including John Adams, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock––implored the Congress to support the Massachusetts militia, who without supplies were laying siege to Boston. Meanwhile, many delegates from the Middle Colonies––including New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia––took a more moderate position, calling for renewed attempts at reconciliation. In the South, the Virginia delegation contained radicals such as Richard Henry Lee and Thomas Jefferson, while South Carolina’s delegation included moderates like John and Edward Rutledge. The moderates worried that supporting the Massachusetts militia would be akin to declaring war.

The Congress struck a compromise, agreeing to adopt the Massachusetts militia and form a Continental Army, naming Virginia delegate, George Washington, commander-in-chief. They also issued a “Declaration of the Causes of Necessity of Taking Up Arms” to justify this decision. At the same time, the moderates drafted an “Olive Branch Petition” which assured the King that the colonists “most ardently desire[d] the former Harmony between [the mother country] and these Colonies.” Many understood that the opportunities for reconciliation were running out . . . Congress was in the strange position of attempting reconciliation while publicly raising an army.

The petition arrived in England on August 13, 1775, but, before it was delivered, the King issued his own “Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition.” He believed his subjects in North America were being “misled by dangerous and ill-designing men,” who, were “traitorously preparing, ordering, and levying war against us.” In an October speech to Parliament, he dismissed the colonists’ petition. The King had no doubt that the resistance was “manifestly carried on for the purpose of establishing an independent empire.” By the start of 1776, talk of independence was growing while the prospect of reconciliation dimmed.

In the opening months of 1776, independence, for the first time, became part of the popular debate. Town meetings throughout the colonies approved resolutions in support of independence. Yet, with moderates still hanging on, it would take another seven months before the Continental Congress officially passed the independence resolution. A small forty-six-page pamphlet published in Philadelphia and written by a recent immigrant from England captured the American conversation. Thomas Paine’s Common Sense argued for independence by denouncing monarchy and challenging the logic behind the British Empire, saying, “There is something absurd, in supposing a continent to be perpetually governed by an island.” His combination of easy language, biblical references, and fiery rhetoric proved potent and the pamphlet was quickly published throughout the colonies. Arguments over political philosophy and rumors of battlefield developments filled taverns throughout the colonies.

George Washington had taken control of the army and after laying siege to Boston forced the British to retreat to Halifax. In Virginia, the royal governor, Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation declaring martial law and offering freedom to “all indentured servants, Negros, and others” if they would leave their masters and join the British. Though only about 500-1000 slaves joined Lord Dunmore’s “Ethiopian regiment,” thousands more flocked to the British later in the war, risking capture and punishment for a chance at freedom. Former slaves occasionally fought, but primarily served in companies called “Black Pioneers” as laborers, skilled workers, and spies. British motives for offering freedom were practical rather than humanitarian, but the proclamation was the first mass emancipation of enslaved people in American history. Slaves could now choose to run and risk their lives for possible freedom with the British army or hope that the United States would live up to its ideals of liberty . . .

Dunmore’s Proclamation had the additional effect of pushing many white Southerners into rebellion. After the Somerset case in 1772 abolished slavery on the British mainland, some American slave-owners began to worry about the growing abolitionist movement in the mother country. Somerset and now Dunmore began to convince some slave owners that a new independent nation might offer a surer protection for slavery. Indeed, the Proclamation laid the groundwork for the very unrest that loyal southerners had hoped to avoid. Consequently, slaveholders often used violence to prevent their slaves from joining the British or rising against them. Virginia enacted regulations to prevent slave defection, threatening to ship rebellious slaves to the West Indies or execute them. Many masters transported their enslaved people inland, away from the coastal temptation to join the British armies, sometimes separating families in the process.

On May 10, 1776, nearly two months before the Declaration of Independence, the Congress voted a resolution calling on all colonies that had not already established revolutionary governments to do so and to wrest control from royal officials. The Congress also recommended that the colonies should begin preparing new written constitutions. In many ways, this was the Congress’s first declaration of independence. A few weeks later, on June 7, Richard Henry Lee offered the following resolution:

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, Free and Independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Delegates went scurrying back to their assemblies for new instructions and nearly a month later, on July 2, the resolution finally came to a vote. It was passed 12-0 with New York, under imminent threat of British invasion, abstaining.

The passage of Lee’s resolution was the official legal declaration of independence, but, between the proposal and vote, a committee had been named to draft a public declaration in case the resolution passed. Virginian Thomas Jefferson drafted the document, with edits being made by his fellow committee members John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, and then again by the Congress as a whole. The famous preamble went beyond the arguments about the rights of British subjects under the British Constitution, instead referring to “natural law”:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.

The majority of the document outlined a list of specific grievances that the colonists had with British attempts to reform imperial administration during the 1760s and 1770s. An early draft blamed the British for the transatlantic slave trade and even for discouraging attempts by the colonists to promote abolition. Delegates from South Carolina and Georgia as well as those from northern states who profited from the trade all opposed this language, and it was removed.

Neither the grievances nor the rhetoric of the preamble were new. Instead, they were the culmination of both a decade of popular resistance to imperial reform and decades more of long-term developments that saw both sides develop incompatible understandings of the British Empire and the colonies’ place within it. The Congress approved the document on July 4, 1776. However, it was one thing to declare independence; it was quite another to win it on the battlefield.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The American Revolution: The War for Independence

The war began at Lexington and Concord, more than a year before Congress declared independence. In 1775, the British believed that the mere threat of war and a few minor incursions to seize supplies would be enough to cow the colonial rebellion. Those minor incursions, however, turned into a full-out military conflict. Despite an early American victory at Boston, the new states faced the daunting task of taking on the world’s largest military.

In the summer of 1776, the British forces that had abandoned Boston arrived at New York. The largest expeditionary force in British history, including tens of thousands of German mercenaries known as “Hessians” followed soon after. New York was the perfect location to launch expeditions aimed at seizing control of the Hudson River and isolating New England from the rest of the continent. Also, New York contained many loyalists, particularly among its merchant and Anglican communities. In October, the British finally launched an attack on Brooklyn and Manhattan. The Continental Army took severe losses before retreating through New Jersey. With the onset of winter, Washington needed something to lift morale and encourage reenlistment. Therefore, he launched a successful surprise attack on the Hessian camp at Trenton on Christmas Day, by ferrying the few thousand men he had left across the Delaware River under the cover of night. The victory won the Continental Army much needed supplies and a morale boost following the disaster at New York.

An even greater success followed in upstate New York. In 1777, in an effort to secure the Hudson River, British General John Burgoyne led an army from Canada through upstate New York. There, he was to meet up with a detachment of General Howe’s forces marching north from Manhattan. However, Howe abandoned the plan without telling Burgoyne and instead sailed to Philadelphia to capture the new nation’s capital. The Continental Army defeated Burgoyne’s men at Saratoga, New York. This victory proved a major turning point in the war. Benjamin Franklin had been in Paris trying to secure a treaty of alliance with the French. However, the French were reluctant to back what seemed like an unlikely cause. News of the victory at Saratoga convinced the French that the cause might not have been as unlikely as they had thought. A “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” was signed on February 6, 1778. The treaty effectively turned a colonial rebellion into a global war as fighting between the British and French soon broke out in Europe and India.

Howe had taken Philadelphia in 1777 but returned to New York once winter ended. He slowly realized that European military tactics would not work in North America. In Europe, armies fought head-on battles in attempt to seize major cities. However, in 1777, the British had held Philadelphia and New York and yet still weakened their position. Meanwhile, Washington realized after New York that the largely untrained Continental Army could not win head-on battles with the professional British army. So he developed his own logic of warfare that involved smaller, more frequent skirmishes and avoided major engagements that would risk his entire army. As long as he kept the army intact, the war would continue, no matter how many cities the British captured.

In 1778, the British shifted their attentions to the South, where they believed they enjoyed more popular support. Campaigns from Virginia to South Carolina and Georgia captured major cities but the British simply did not have the manpower to retain military control. And, upon their departures, severe fighting ensued between local patriots and loyalists, often pitting family members against one another. The War in the South was truly a civil war.

By 1781, the British were also fighting France, Spain, and Holland. The British public’s support for the costly war in North America was quickly waning. The Americans took advantage of the British southern strategy with significant aid from the French army and navy. In October, Washington marched his troops from New York to Virginia in an effort to trap the British southern army under the command of Gen. Charles Cornwallis. Cornwallis had dug his men in at Yorktown awaiting supplies and reinforcements from New York. However, the Continental and French armies arrived first, quickly followed by a French navy contingent, encircling Cornwallis’s forces and, after laying siege to the city, forcing his surrender. The capture of another army left the British without a new strategy and without public support to continue the war. Peace negotiations took place in France, and the war came to an official end on September 3, 1783 with the Treaty of Paris.

Americans celebrated their victory, but it came at great cost. Soldiers suffered through brutal winters with inadequate resources. During the single winter at Valley Forge in 1777-8, over 2,500 Americans died from disease and exposure. Life was not easy on the home front either. Women on both sides of the conflict were frequently left alone to care for their households. In addition to their existing duties, women took on roles usually assigned to men on farms and in shops and taverns. Abigail Adams addressed the difficulties she encountered while “minding family affairs” on their farm in Braintree, Massachusetts. Abigail managed the planting and harvesting of crops, in the midst of severe labor shortages and inflation, while dealing with several tenants on the Adams’ property, raising her children, and making clothing and other household goods. In order to support the family economically during John’s frequent absences and the uncertainties of war, Abigail also invested in several speculative schemes and sold imported goods.

While Abigail remained safely out of the fray, other women were not so fortunate. The Revolution was not only fought on distant battlefields. It was fought on women’s very doorsteps, in the fields next to their homes. There was no way for women to avoid the conflict, or the disruptions and devastations it caused. As the leader of the state militia during the Revolution, Mary Silliman’s husband, Gold, was absent from their home for much of the conflict. On the morning of July 7, 1779, when a British fleet attacked nearby Fairfield, Connecticut, it was Mary who calmly evacuated her household, including her children and servants, to North Stratford. When Gold was captured by loyalists and held prisoner, Mary, six months pregnant with their second child, wrote letters to try to secure his release. When such appeals were ineffectual, Mary spearheaded an effort, along with Connecticut Governor, John Trumbull, to capture a prominent Tory leader to exchange for her husband’s freedom.

Slaves and free black Americans also impacted (and were impacted by) the Revolution. The British were the first to recruit black regiments, as early as Dunmore’s Proclamation of 1775 in Virginia, which promised freedom to any slaves who would escape their masters and join the British cause. At first, Washington, a slaveholder himself, resisted allowing black men to join the Continental Army, but he eventually relented. In 1775, Peter Salem’s master freed him to fight with the militia. Salem faced British Regulars in the battles at Lexington and Bunker Hill, where he fought valiantly with around three-dozen other black Americans. Salem not only contributed to the cause, but he earned the ability to determine his own life after his enlistment ended. Salem was not alone, but many more slaves seized upon the tumult of war to run away and secure their own freedom directly. Historians estimate that between 30,000 and 100,000 slaves deserted their masters during the war.

Men and women together struggled through years of war and hardship. For patriots (and those who remained neutral), victory brought new political, social, and economic opportunities, but it also brought new uncertainties. The war decimated entire communities, particularly in the South. Thousands of women throughout the nation had been widowed. The American economy, weighed down by war debt and depreciated currencies, would have to be rebuilt following the war. State constitutions had created governments, but now men would have to figure out how to govern. The opportunities created by the Revolution had come at great cost, in both lives and fortune, and it was left to the survivors to seize those opportunities and help forge and define the new nation-state.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The American Revolution

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence

Khan Academy. The Declaration of Independence. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-us-history/period-3/apush-the-american-revolution/v/the-declaration-of-independence

The War for Independence

Pulley, P. American Revolution, Part 2. (2013, February 19). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDYYlViE99w

Summary

American colonists fought against Britain to win independence from the British Empire. The Declaration of Independence asserts that all peoples have a right to form their own government. The document also asserts that “all men are created equal.” The Declaration of Independence is filled with lofty ideals. The realities of the Revolutionary War were far more harsh. Thousands of men and women fought and died in the conflict. One of the most crucial aspects of the war was the alliance formed between the American patriots and France. France was a powerful empire and a great rival of Britain. Without the support of France, it is unlikely that the American colonists could have won independence from Britain. Ultimately, at the end of the war, George Washington received great praise and fame for leading the Continental Army to victory.