The seventeenth century saw the establishment and solidification of the British North American colonies, but this process did not occur peacefully. English settlements on the continent were rocked by explosions of violence, including the Pequot War, the Mystic massacre, King Philip’s War, the Susquehannock War, Bacon’s Rebellion, and the Pueblo Revolt. These conflicts reveal the complex and often violent interactions between colonists and indigenous peoples of North America.

Source: Gregory Ablavsky et al., “British North America,” Daniel Johnson, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Defending Native America

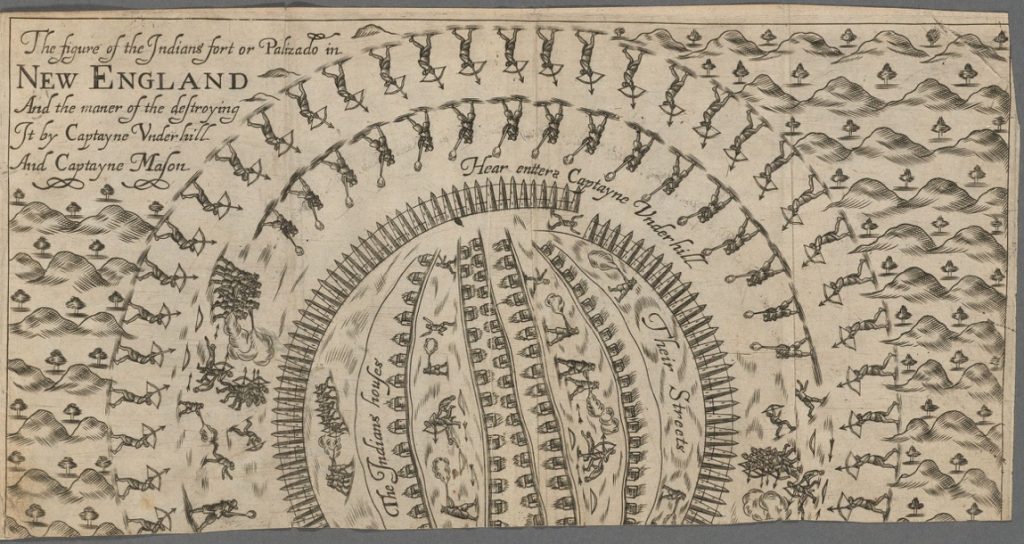

In May 1637, an armed contingent of English Puritans from Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut colonies trekked into Indian country in territory claimed by New England. Referring to themselves as the “Sword of the Lord,” this military force intended to attack “that insolent and barbarous Nation, called the Pequots.” In the resulting violence, Puritans put the Mystic community to the torch, beginning with the north and south ends of the town. As Pequot men, women, and children tried to escape the blaze, other soldiers waited with swords and guns. One commander estimated that of the “four hundred souls in this Fort…not above five of them escaped out of our hands,” although another counted near “six or seven hundred” dead. In a span of less than two months, the English Puritans boasted that the Pequot “were drove out of their country, and slain by the sword, to the number of fifteen hundred.”

The foundations of the war lay within the rivalry between the Pequot, the Narragansett, and the Mohegan, who battled for control of the fur and wampum trades in the northeast. This rivalry eventually forced the English and Dutch to choose sides. The war remained a conflict of Native interests and initiative, especially as the Mohegan hedged their bets on the English and reaped the rewards that came with displacing the Pequot. Victory over the Pequots not only provided security and stability for the English colonies, but also propelled the Mohegan to new heights of political and economic influence as the primary power in New England.

Ironically, history seemingly repeated itself later in the century as the Mohegan, desperate for a remedy to their diminishing strength, joined the Wampanoag war against the Puritans. This produced a more violent conflict in 1675 known as King Philip’s War, bringing a decisive end to Indian power in New England. In the winter of 1675, the body of John Sassamon, a Christian, Harvard-educated Wampanoag, was found under the ice of a nearby pond. A fellow Christian Indian informed English authorities that three warriors under the local sachem named Metacom, known to the English as King Philip, had killed Sassamon, who had previously accused Metacom of planning an offensive against the English. The three alleged killers appeared before the Plymouth court in June 1675. They were found guilty of murder, and executed. Several weeks later, a group of Wampanoags killed nine English colonists in the town of Swansea.

Metacom—like most other New England sachems—had entered into covenants of “submission” to various colonies, viewing the arrangements as relationships of protection and reciprocity rather than subjugation. Indians and English lived, traded, worshiped, and arbitrated disputes in close proximity before 1675; but the execution of three of Metacom’s men at the hands of Plymouth Colony epitomized what many Indians viewed as the growing inequality of that relationship. The Wampanoags who attacked Swansea may have sought to restore balance, or to retaliate for the recent executions. Neither they nor anyone else sought to engulf all of New England in war, but that is precisely what happened. Authorities in Plymouth sprung into action, enlisting help from the neighboring colonies of Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Metacom and his followers eluded colonial forces in the summer of 1675, striking more Plymouth towns as they moved northwest. Some groups joined his forces, while others remained neutral or supported the English. The war badly divided some Indian communities. Metacom himself had little control over events, as panic and violence spread throughout New England in the autumn of 1675. English mistrust of neutral Indians, sometimes accompanied by demands they surrender their weapons, pushed many into open war. By the end of 1675, most of the Indians of present-day western and central Massachusetts had entered the war, laying waste to nearby English towns like Deerfield, Hadley, and Brookfield. Hapless colonial forces, spurning the military assistance of Indian allies such as the Mohegans, proved unable to locate more mobile native communities or intercept Indian attacks. The English compounded their problems by attacking the powerful and neutral Narragansetts of Rhode Island in December 1675. In an action called the Great Swamp Fight, 1,000 Englishmen put the main Narragansett village to the torch, gunning down as many as 1,000 Narragansett men, women, and children as they fled the maelstrom. The surviving Narragansetts joined the Indians already fighting the English. Between February and April 1676, Native forces devastated a succession of English towns closer and closer to Boston.

In the spring of 1676, the tide turned. The New England colonies took the advice of men like Benjamin Church, who urged the greater use of Native allies, including Pequots and Mohegans, to find and fight the mobile warriors. Unable to plant crops and forced to live off the land, Indians’ will to continue the struggle waned as companies of English and Native allies pursued them. Growing numbers of fighters fled the region, switched sides, or surrendered in the spring and summer. The English sold many of the latter group into slavery. Colonial forces finally caught up with Metacom in August 1676, and the sachem was slain by a Christian Indian fighting with the English. The war permanently altered the political and demographic landscape of New England. Between 800 and 1,000 English and at least 3,000 Indians perished in the 14-month conflict. Thousands of other Indians fled the region or were sold into slavery. In 1670, Native Americans comprised roughly 25 percent of New England’s population; a decade later, they made up perhaps 10 percent. The war’s brutality also encouraged a growing hatred of all Indians among many New England colonists.

Just a few years after King Philip’s War, the Spanish experienced their own tumult in the area of contemporary New Mexico. The Spanish had been maintaining control partly by suppressing Native American beliefs. Friars aggressively enforced Catholic practice, burning native idols and masks and other sacred objects and banishing traditional spiritual practices. In 1680 the Pueblo religious leader Popé, who had been arrested and whipped for “sorcery” five years earlier, led various Puebloan groups in rebellion. Several thousand Pueblo warriors razed the Spanish countryside and besieged Santa Fe. They killed 400, including 21 Franciscan priests, and allowed 2,000 other Spaniards and Christian Pueblos to flee. It was perhaps the greatest act of Indian resistance in North American history.

In New Mexico, the Pueblos eradicated all traces of Spanish rule. They destroyed churches and threw themselves into rivers to wash away their Christian baptisms. “The God of the Christians is dead,” Popé proclaimed, and the Pueblo resumed traditional spiritual practices. The Spanish were exiled for twelve years. They returned in 1692, weakened, to reconquer New Mexico.

The late seventeenth century was a time of great violence and turmoil. Bacon’s Rebellion turned white Virginians against one another, King Philip’s War shattered Indian resistance in New England, and the Pueblo Revolt struck a major blow to Spanish power. It would take several more decades before similar patterns erupted in Carolina and Pennsylvania, but the constant advance of European settlements provoked conflict in these areas as well. In 1715, the Yamasees, Carolina’s closest allies and most lucrative trading partners, turned against the colony and nearly destroyed it entirely. Writing from Carolina to London, the settler George Rodd believed the Yamasees wanted nothing less than “the whole continent and to kill us or chase us all out.” Yamasees would eventually advance within miles of Charles Town. The Yamasee War’s first victims were traders. The governor had dispatched two of the colony’s most prominent men to visit and pacify a Yamasee council following rumors of native unrest. Yamasees quickly proved the fears well founded by killing the emissaries and every English trader they could corral.

Yamasees, like many other Indians, had come to depend on English courts as much as the flintlock rifles and ammunition traders offered them for slaves and animal skins. Feuds between English agents in Indian country had crippled the court of trade and shut down all diplomacy, provoking the violent Yamasee reprisal. Most Indian villages in the southeast sent at least a few warriors to join what quickly became a pan-Indian cause against the colony. Yet Charles Town ultimately survived the onslaught by preserving one crucial alliance with the Cherokees. By 1717, the conflict had largely dried up, and the only remaining menace was roaming Yamasee bands operating from Spanish Florida. Most Indian villages returned to terms with Carolina and resumed trading. The lucrative trade in Indian slaves, however, which had consumed 50,000 souls in five decades, largely dwindled after the war. The danger was too high for traders, and the colonies discovered even greater profits by importing Africans to work new rice plantations. Herein lies the birth of the “Old South,” that expanse of plantations that created untold wealth and misery. Indians retained the strongest militaries in the region, but they never again threatened the survival of English colonies.

If a colony existed where peace with Indians might continue, it would be Pennsylvania. At the colony’s founding William Penn created a Quaker religious imperative for the peaceful treatment of Indians. While Penn never doubted that the English would appropriate Native lands, he demanded his colonists obtain Indian territories through purchase rather than violence. Though Pennsylvanians maintained relatively peaceful relations with Native Americans, increased immigration and booming land speculation increased the demand for land. Coercive and fraudulent methods of negotiation became increasingly prominent. The Walking Purchase of 1737 was emblematic of both colonists’ desire for cheap land and the changing relationship between Pennsylvanians and their Native neighbors. Through treaty negotiation in 1737, native Delaware leaders agreed to sell Pennsylvania all of the land that a man could walk in a day and a half, a common measurement utilized by Delawares in evaluating distances. John and Thomas Penn, joined by the land speculator and longtime friend of the Penns James Logan, hired a team of skilled runners to complete the “walk” on a prepared trail. The runners traveled from Wrightstown to present-day Jim Thorpe and proprietary officials then drew the new boundary line perpendicular to the runners’ route, extending northeast to the Delaware River. The colonial government thus measured out a tract much larger than Delawares had originally intended to sell, roughly 1,200 square miles. As a result, Delaware-proprietary relations suffered. Many Delawares left the lands in question and migrated westward to join Shawnees and other Delawares already living in the Ohio Valley. There, they established diplomatic and trade relationships with the French. Memories of the suspect purchase endured into the 1750s and became a chief point of contention between the Pennsylvanian government and Delawares during the upcoming Seven Years War.

Source: Gregory Ablavsky et al., “British North America,” Daniel Johnson, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.

Defending Native America – Video

Defending Native America

Crash Course US History. 2013, February 14. The Natives and the English. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TTYOQ05oDOI.

Summary

The seventeenth century saw the creation and maturation of Britain’s North American colonies. Throughout that period, tensions between colonists and Native Americans reached new heights, often leading to violence. At times, Native Americans formed alliances with colonial powers in opposition to their traditional Native American enemies. At other points, Native Americans formed broad coalitions in order to halt further colonial encroachment and authority over their land and territory. In New England, conflicts such as the Mystic Massacre in 1637 and King Philip’s War in 1675 shaped colonial and indigenous relations. In Virginia, conflict between Native Americans, rebels and colonial authorities came to a head in Bacon’s Rebellion, a conflict that was centrally focused on the colony’s relations with the Doeg and Susquehannock. And similar patterns of violence and unrest between Native Americans and colonists would also emerge in New Mexico, the Carolinas, and Pennsylvania. These conflicts would leave a lasting legacy on the Americas, and reveal the uneasy and often violent relations that developed between the colonists in British North America and the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

Source: Gregory Ablavsky et al., “British North America,” Daniel Johnson, ed., in The American Yawp, Joseph Locke and Ben Wright, eds., last modified August 1, 2017, http://www.AmericanYawp.com.