By the 1840s, the United States economy bore little resemblance to the import-and-export economy of colonial days. It was now a market economy, one in which the production of goods, and their prices, were unregulated by the government. Commercial centers, to which job seekers flocked, mushroomed. New opportunities for wealth appeared to be available to anyone.

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who traveled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems. People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress. Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established system of railroads.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014

Family Farm to Industrial Farm

In the early nineteenth century, people poured into the territories west of the long-settled eastern seaboard. Among them were speculators seeking to buy cheap parcels from the federal government in anticipation of a rise in prices. The Ohio Country in the Northwest Territory appeared to offer the best prospects for many in the East. The result was “Ohio fever,” as thousands traveled there to reap the benefits of settling in this newly available territory.

The federal government oversaw the orderly transfer of public land to citizens at public auctions. The Land Law of 1796 applied to the territory of Ohio. Under this law, the United States would sell a minimum parcel of 640 acres for $2 an acre. The Land Law of 1800 further encouraged land sales in the Northwest Territory by reducing the minimum parcel size by half and enabling sales on credit, with the goal of stimulating settlement by ordinary farmers. The government created land offices to handle these sales and established them in the West within easy reach of prospective landowners. They could thus purchase land directly from the government, at the price the government had set. Buyers were given low interest rates, with payments that could be spread over four years. Surveyors marked off the parcels in straight lines, creating a landscape of checkerboard squares.

The future looked bright for those who turned their gaze on the land in the West. Surveying, settling, and farming, turning the wilderness into a profitable commodity, gave purchasers a sense of progress.

In an effort to stimulate the economy in the midst of the economic depression of 1819, Congress passed several acts modifying land sales. The Land Law of 1820 lowered the price of land to $1.25 per acre and allowed small parcels of eighty acres to be sold. States, too, attempted to aid those faced with economic hard times by passing laws to prevent mortgage foreclosures so buyers could keep their homes. Americans made the best of the opportunities presented in business, in farming, or on the frontier, and by 1823 the Panic of 1819 had ended.

The volatility of the U.S. economy did nothing to dampen the creative energies of its citizens in the years before the Civil War. In the 1800s, a frenzy of entrepreneurship and invention yielded many new products and machines. The republic seemed to be a laboratory of innovation.

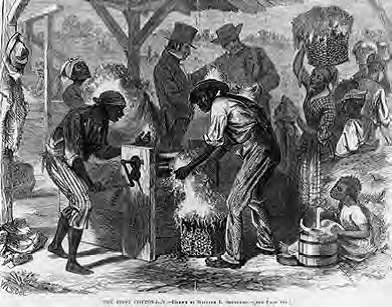

One of the most influential advancements of the early nineteenth century was the cotton engine or gin, invented by Eli Whitney and patented in 1794. Whitney, who was born in Massachusetts, had spent time in the South and knew that a device to speed up the production of cotton was desperately needed so cotton farmers could meet the growing demand for their crop. Whitney’s seemingly simple invention cleaned the seeds from the raw cotton far more quickly and efficiently than could slaves working by hand. The raw cotton with seeds was placed in the cotton gin, and with the use of a hand crank, the seeds were extracted through a carding device that aligned the cotton fibers in strands for spinning.

Another influential new technology of the early 1800s was the steamship engine, invented by Robert Fulton in 1807. Fulton’s first steamship, the Clermont, used paddle wheels to travel the 150 miles from New York City to Albany in a record time of only thirty-two hours. Soon, a fleet of steamboats was traversing the Hudson River and New York Harbor, later expanding to travel every major American river including the mighty Mississippi. By the 1830s there were over one thousand of these vessels, radically changing water transportation by ending its dependence on the wind. Steamboats could travel faster and more cheaply than sailing vessels or keelboats. Steamboats also arrived with much greater dependability. The steamboat facilitated the rapid economic development of the massive Mississippi River Valley and the settlement of the West.

Virginia-born Cyrus McCormick wanted to replace the laborious process of using a scythe to cut and gather wheat for harvest. In 1831, he and the slaves on his family’s plantation tested a horse-drawn mechanical reaper, and over the next several decades, he made constant improvements to it. More farmers began using it in the 1840s, and greater demand for the McCormick reaper led McCormick

and his brother to establish the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago, where labor was more readily available. By the 1850s, McCormick’s mechanical reaper had enabled farmers to vastly increase their output. McCormick—and also John Deere, who improved on the design of plows—opened the prairies to agriculture. McCormick’s bigger machine could harvest grain faster, and Deere’s plow could cut through the thick prairie sod. Agriculture north of the Ohio River became the pantry that would lower food prices and feed the major cities in the East. In short order, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois all become major agricultural states.

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road, a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travelers immense amounts of time and money. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal, which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress.

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed,

the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. People at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the market revolution would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014

Family Farm to Industrial Farm – Video

EMS History. A Transportation Revolution. (18 March 2012). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N5FDMIDcyn0&t=159s

Summary

In the early nineteenth century, the land of the Midwest was opened to large scale agricultural development. A number of factors contributed to the economic development of the Midwest. The federal government promoted the sale of land in the Northwest territory through the Land Law of 1796 and the Land Law of 1800, which allowed individuals to purchase land cheaply on credit. The federal government and state governments provided funding for canals, roads, and railways to link the Midwest with the East Coast, which enabled goods to be shipped from the Midwest to ports in the East. The Erie Canal brought great commerce and wealth to New York City by linking the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. Inventions also promoted agricultural development in the Midwest. The invention of the mechanical reaper by Cyrus McCormick enabled farmers to expand production. The invention of the steam boat and steam locomotive made it easier to transport goods from the Midwest to the port cities in the East. President John Quincy Adams did more than any other president to promote the development of improved transportation systems in the United States in the early nineteenth century.