Early in the war, President Lincoln approached the issue of slavery cautiously. While he disapproved of slavery, he did not believe that he had the authority to abolish it. Furthermore, he feared that making the abolition of slavery an objective of the war would cause the border slave states to join the Confederacy. His one objective in 1861 and 1862 was to restore the Union.

It was slaves themselves that pressed the federal government to take action against the institution of slavery. Since the beginning of the war, thousands of slaves had fled to the safety of Union lines. This placed pressure on the Union government to determine the status of these persons. In May 1861, Union general Benjamin Butler and others labeled these refugees from slavery contrabands. Butler reasoned that since Southern states had left the United States, he was not obliged to follow federal fugitive slave laws. Slaves who made it through the Union lines were shielded by the U.S. military and not returned to slavery. This was the first of a series of actions that would culminate in the Emancipation Proclamation.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Pushing Emancipation

While Lincoln, his cabinet, and the War Department devised strategies to defeat the rebel insurrection, black Americans quickly forced the issue of slavery as a primary issue in the debate. As early as 1861, black Americans implored the Lincoln administration to serve in the army and navy. Lincoln initially waged a conservative, limited war. He believed that the presence of African American troops would threaten the loyalty of slaveholding border states, and white volunteers might refuse to serve alongside black men. However, army commanders could not ignore the growing populations of formerly enslaved people who escaped to freedom behind Union army lines. These former enslaved people took a proactive stance early in the war and forced the federal government to act. As the number of refugees ballooned, Lincoln and Congress found it harder to avoid the issue.

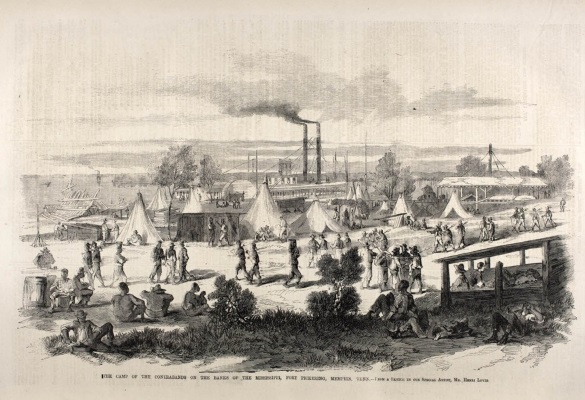

In May 1861, General Benjamin F. Butler went over his superiors’ heads and began accepting fugitive slaves who came to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. In order to avoid the issue of the slaves’ freedom, Butler reasoned that runaway slaves were “contraband of war,” and he had as much a right to seize them as he did to seize enemy horses or cannons. Later that summer Congress affirmed Butler’s policy in the First Confiscation Act. The act left “contrabands,” as these runaways were called, in a state of limbo. Once a slave escaped to Union lines, her master’s claim was nullified. She was not, however, a free citizen of the United States. Runaways lived in “contraband camps,” where disease and malnutrition were rampant. Women and men were required to perform the drudgework of war: raising fortifications, cooking meals, and laying railroad tracks. Still, life as a contraband offered a potential path to freedom, and thousands of slaves seized the opportunity.

Fugitive slaves posed a dilemma for the Union military. Soldiers were forbidden to interfere with slavery or assist runaways, but many soldiers found such a policy unchristian. Even those indifferent to slavery were reluctant to turn away potential laborers or help the enemy by returning his property. Also, fugitive slaves could provide useful information on the local terrain and the movements of Confederate troops. Union officers became particularly reluctant to turn away fugitive slaves when Confederate commanders began forcing slaves to work on fortifications. Every slave who escaped to Union lines was a loss to the Confederate war effort.

By the summer of 1862, the actions of black Americans were pushing the Union towards a full-blown war of emancipation. Following the First Confiscation Act, in April 1862, Congress abolished the institution of slavery in the District of Columbia. In July 1862, Congress passed the 2nd Confiscation Act, effectively emancipating slaves that came under Union control. Word traveled fast among enslaved people, and this legislation led to even more runaways making their way into Union lines. Abraham Lincoln’s thinking began to evolve. By the summer of 1862, Lincoln first floated the idea of an Emancipation Proclamation to members of his Cabinet. By August 1862, he proposed the first iteration of the Emancipation Proclamation. While his cabinet supported such an idea, Secretary of State William Seward insisted that Lincoln wait for a “decisive” Union victory so as not to appear too desperate a measure on the part of a failing government.

This decisive moment that prompted the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation would occur in the fall of 1862 along Antietam creek in Maryland. Emboldened by their success in the previous spring and summer, Lee and Confederate President Jefferson Davis planned to win a decisive victory in Union territory and end the war. On September 17, 1862, McClellan and Lee’s forces collided at the Battle of Antietam near the town of Sharpsburg. This battle was the first major battle of the Civil War to occur on Union soil. It remains the bloodiest single day in American history with over 20,000 soldiers killed, wounded, or missing in just twelve hours.

Despite the Confederate withdrawal and the high death toll, the Battle of Antietam was not a decisive Union victory. It did, however, result in enough of a victory for Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in areas under Confederate control. There were significant exemptions to the Emancipation Proclamation including the border states, and parts of other states in the Confederacy. A far cry from a universal end to slavery, the Emancipation Proclamation nevertheless proved vital shifting the war aims from simple union to Emancipation. Framing it as a war measure, Lincoln and his Cabinet hoped that stripping the Confederacy of their labor force would not only debilitate the Southern economy, but also weaken Confederate morale. Furthermore, the Battle of Antietam and the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation all but ensured that the Confederacy would not be recognized by European powers. Nevertheless, Confederates continued fighting. Union and Confederate forces clashed again at Fredericksburg, Virginia in December 1862. This Confederate victory resulted in staggering Union casualties.

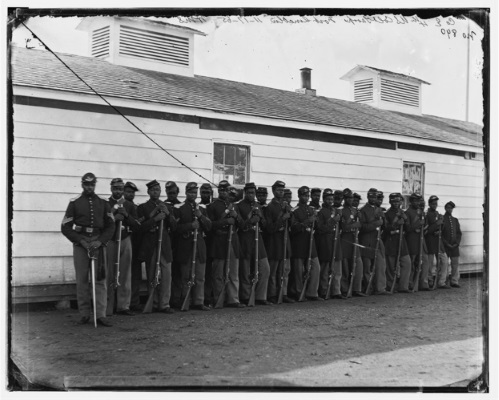

As United States armies penetrated deeper into the Confederacy, politicians and the Union high command came to understand the necessity, and benefit, of enlisting black men in the army and navy. Although a few commanders began forming black units in 1862, such as Massachusetts abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s First South Carolina Volunteers (the first regiment of black soldiers), widespread enlistment did not occur until the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect on January 1, 1863. “And I further declare and make known,” Lincoln’s Proclamation read, “that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.”

The language describing black enlistment indicated Lincoln’s implicit desire to segregate African American troops from the main campaigning armies of white soldiers. “I believe it is a resource which, if vigorously applied now, will soon close the contest. It works doubly, weakening the enemy and strengthening us,” Lincoln remarked in August 1863 about black soldiering. Although more than 180,000 black men (ten percent of the Union army) served during the war, the majority of United States Colored Troops (USCT) remained stationed behind the lines as garrison forces, often laboring and performing non-combat roles.

Black soldiers in the Union army endured rampant discrimination and earned less pay than white soldiers, while also facing the possibility of being murdered or sold into slavery if captured. James Henry Gooding, a black corporal in the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, wrote to Abraham Lincoln in September 1863, questioning why he and his fellow volunteers were paid less than white men. Gooding argued that, because he and his brethren were born in the United States and selflessly left their private lives and to enter the army, they should be treated “as American soldiers, not as menial hirelings.”

African American soldiers defied the inequality of military service and used their positions in the army to reshape society, North and South. The majority of USCT (United States Colored Troops) had once been enslaved, and their presence as armed, blue-clad soldiers sent shockwaves throughout the Confederacy. To their friends and families, African American soldiers symbolized the embodiment of liberation and the destruction of slavery. To white southerners, they represented the utter disruption of the Old South’s racial and social hierarchy. As members of armies of occupation, black soldiers wielded martial authority in towns and plantations. At the end of the war, as a black soldier marched by a cluster of Confederate prisoners, he noticed his former master among the group. “Hello, massa,” the soldier exclaimed, “bottom rail on top dis time!”

The majority of USCT occupied the South by performing garrison duty, other black soldiers performed admirably on the battlefield, shattering white myths that docile, cowardly black men would fold in the maelstrom of war. Black troops fought in more than 400 battles and skirmishes, including Milliken’s Bend and Port Hudson, Louisiana; Fort Wagner, South Carolina; Nashville; and the final campaigns to capture Richmond, Virginia. Fifteen black soldiers received the Medal of Honor, the highest honor bestowed for military heroism. Through their voluntarism, service, battlefield contributions, and even death, black soldiers laid their claims for citizenship. “Once let a black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.” Frederick Douglass, the great black abolitionist, proclaimed, “and there is no power on earth which can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship.”

Many slaves accompanied their masters in the Confederate army. They served their masters as “camp servants,” cooking their meals, raising their tents, and carrying their supplies. The Confederacy also impressed slaves to perform manual labor. There are three important points to make about these “Confederate” slaves. First, their labor was almost always coerced. Second, people are complicated and have varying, often contradictory loyalties. A slave could hope in general that the Confederacy would lose but at the same time be concerned for the safety of his master and the Confederate soldiers he saw on a daily basis.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

Pushing Emancipation

Foner, E. The Rising Tide of Emancipation: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1865. (2015, January 19). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yTFYu2oXk0s

Foner, E. The Emancipation Proclamation: The Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1865. (2015, January 19). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vxjyt6hD1Wg

Summary

The Civil War would ultimately result in the abolition of slavery. At the beginning of the war, President Lincoln did not intend to abolish slavery. Slaves themselves pressed the issue of emancipation by escaping and running to the Union lines. The Union Army and government was forced to consider what to do with slaves who escaped to Union lines. Under the terms of the First Confiscation Act, escaped slaves were defined as contraband of war; they would not be returned to their masters, but they were not granted freedom. Under the terms of the Second Confiscation Act, slaves who escaped to Union lines were granted freedom. Congress also enacted a law to emancipate all slaves in the nation’s capital, Washington D.C. Finally, as the war dragged on and casualties mounted, President Lincoln decided to free all slaves in the Confederacy. Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that all slaves in the Confederate states would be free. The Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to slaves residing in states within the Union such as Maryland. After the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, African Americans were actively recruited into the Union Army.