By the 1830s, the United States had developed a thriving industrial and commercial sector in the Northeast. Farmers embraced regional and distant markets as the primary destination for their products. Artisans witnessed the methodical division of the labor process in factories. Wage labor became an increasingly common experience. These industrial and market revolutions, combined with advances in transportation, transformed the economic and social landscape. Americans could now quickly produce larger amounts of goods for a nationwide, and sometimes an international, market and rely less on foreign imports than in colonial times.

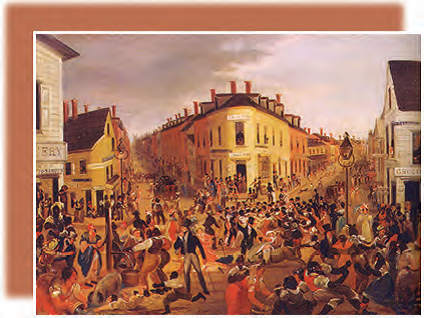

As American economic life shifted rapidly and modes of production changed, new class divisions emerged and solidified, resulting in previously unknown economic and social inequalities. A crowded urban world emerged filled with American day laborers and low wage workers who lived a precarious existence that the economic benefits of the new economy largely bypassed. An influx of immigrant workers swelled and diversified an already crowded urban population. Advances in industrialization and the market revolution came at a human price.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Rise of Urban America

Northern industrialization expanded rapidly following the War of 1812. Industrialized manufacturing began in New England, where wealthy merchants built water-powered textile mills (and mill towns to support them) along the rivers of the Northeast. These mills introduced new modes of production centralized within the confines of the mill itself. As never before, production relied on mechanized sources with water power, and later steam, to provide the force necessary to drive machines. In addition to the mechanization and centralization of work in the mills, specialized, repetitive tasks assigned to wage laborers replaced earlier modes of handicraft production done by artisans at home. The operations of these mills irrevocably changed the nature of work by deskilling tasks, breaking down the process of production to its most basic, elemental parts. In return for their labor, the workers, who at first were young women from rural New England farming families, received wages. From its origin in New England, manufacturing soon spread to other regions of the United States.

In the late 1790s and early 1800s, Great Britain boasted the most advanced textile mills and machines in the world, and the United States continued to rely on Great Britain for finished goods. Great Britain hoped to maintain its economic advantage over its former colonies in North America. So, in an effort to prevent the knowledge of advanced manufacturing from leaving the Empire, the British banned the emigration of mechanics, skilled workers who knew how to build and repair the latest textile machines.

Some skilled British mechanics, including Samuel Slater, managed to travel to the United States in the hopes of profiting from their knowledge and experience with advanced textile manufacturing. Slater understood the workings of the latest water-powered textile mills, which British industrialist

Richard Arkwright had pioneered. In the 1790s in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, Slater convinced several American merchants, including the wealthy Providence industrialist Moses Brown, to finance and build a water-powered cotton mill based on the British models. Slater’s knowledge of both technology and mill organization made him the founder of the first truly successful cotton mill in the United States.

The success of Slater and his partners Smith Brown and William Almy, relatives of Moses Brown, inspired others to build additional mills in Rhode Island and Massachusetts. By 1807, thirteen more mills had been established. President Jefferson’s embargo on British manufactured goods from late 1807 to early 1809 spurred more New England merchants to invest in industrial enterprises. By 1812, seventy-eight new textile mills had been built in rural New England towns. More than half turned out woolen goods, while the rest produced cotton cloth.

Slater’s mills and those built in imitation of his were fairly small, employing only seventy people on average. Workers were organized the way that they had been in English factories, in family units. Under the “Rhode Island system,” families were hired. The father was placed in charge of the family unit, and he directed the labor of his wife and children. Instead of being paid in cash, the father was given “credit” equal to the extent of his family’s labor that could be redeemed in the form of rent (of company-owned housing) or goods from the company-owned store.

The Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 played a pivotal role in spurring industrial development in the United States. Jefferson’s embargo prevented American merchants from engaging in the Atlantic trade, severely cutting into their profits. The War of 1812 further compounded the financial woes of American merchants. The acute economic problems led some New England merchants, including Francis Cabot Lowell, to cast their gaze on manufacturing. Lowell had toured English mills during a stay in Great Britain. He returned to Massachusetts having memorized the designs for the advanced textile machines he had seen in his travels, especially the power loom, which replaced individual hand weavers. Lowell convinced other wealthy merchant families to invest in the creation of new mill towns. In 1813, Lowell and these wealthy investors, known as the Boston Associates, created the Boston Manufacturing Company. Together they raised $400,000 and, in 1814, established a textile mill in Waltham and a second one in the same town shortly thereafter.

At Waltham, cotton was carded and drawn into coarse strands of cotton fibers called rovings. The rovings were then spun into yarn, and the yarn woven into cotton cloth. Yarn no longer had to be put out to farm families for further processing. All the work was now performed at a central location—the factory.

The work in Lowell’s mills was both mechanized and specialized. Specialization meant the work was broken down into specific tasks, and workers repeatedly did the one task assigned to them in the course of a day. As machines took over labor from humans and people increasingly found themselves confined to the same repetitive step, the process of deskilling began.

The Boston Associates’ mills, which each employed hundreds of workers, were located in company towns, where the factories and worker housing were owned by a single company. This gave the owners and their agents control over their workers. The most famous of these company towns was Lowell, Massachusetts. The new town was built on land the Boston Associates purchased in 1821 from the village of East Chelmsford at the falls of the Merrimack River, north of Boston. The mill buildings themselves were constructed of red brick with large windows to let in light. Company-owned boarding houses to shelter employees were constructed near the mills. The mill owners planted flowers and trees to maintain the appearance of a rural New England town and to forestall arguments, made by many, that factory work was unnatural and unwholesome.

In contrast to many smaller mills, the Boston Associates’ enterprises avoided the Rhode Island system, preferring individual workers to families. These employees were not difficult to find. The competition New England farmers faced from farmers now settling in the West, and the growing scarcity of land in population-dense New England, had important implications for farmers’ children. Realizing their chances of inheriting a large farm or receiving a substantial dowry were remote, these teenagers sought other employment opportunities, often at the urging of their parents. While young men could work at a variety of occupations, young women had more limited options. The textile mills provided suitable employment for the daughters of Yankee farm families.

The mechanization of formerly handcrafted goods, and the removal of production from the home to the factory, dramatically increased output of goods. For example, in one nine-month period, the numerous Rhode Island women who spun yarn into cloth on hand looms in their homes produced a total of thirty-four thousand yards of fabrics of different types. In 1855, the women working in just one of Lowell’s mechanized mills produced more than forty-three thousand yards.

The Boston Associates’ cotton mills quickly gained a competitive edge over the smaller mills established by Samuel Slater and those who had imitated him. Their success prompted the Boston Associates to expand. In Massachusetts, in addition to Lowell, they built new mill towns in Chicopee, Lawrence, and Holyoke. In New Hampshire, they built them in Manchester, Dover, and Nashua. And in Maine, they built a large mill in Saco on the Saco River. Other entrepreneurs copied them. By the time of the Civil War, 878 textile factories had been built in New England. All together, these factories employed more than 100,000 people and produced more than 940 million yards of cloth.

Success in New England was repeated elsewhere. Small mills, more like those in Rhode Island than those in northern Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine, were built in New York, Delaware, and Pennsylvania. By midcentury, three hundred textile mills were located in and near Philadelphia. Many produced specialty goods, such as silks and printed fabrics, and employed skilled workers, including people working in their own homes. Even in the South, the region that otherwise relied on slave labor to produce the very cotton that fed the northern factory movement, more than two hundred textile mills were built. Most textiles, however, continued to be produced in New England before the Civil War.

Alongside the production of cotton and woolen cloth, which formed the backbone of the Industrial Revolution in the United States as in Britain, other crafts increasingly became mechanized and centralized in factories in the first half of the nineteenth century. Shoe making, leather tanning, papermaking, hat making, clock making, and gun making had all become mechanized to one degree or another by the time of the Civil War. Flour milling, because of the inventions of Oliver Evans, had become almost completely automated and centralized by the early decades of the nineteenth century. So efficient were Evans-style mills that two employees were able to do work that had originally required five, and mills using Evans’s system spread throughout the mid-Atlantic states.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Rise of Urban America

The transition from an agricultural to an industrial economy took more than a century in the United States, but that long development entered its first phase from the 1790s through the 1830s. The industrial revolution had begun in Britain during the mid-18th century, but the American colonies lagged far behind the mother country in part because the abundance of land and scarcity of labor in the New World reduced interest in expensive investments in machine production. Nevertheless, with the shift from hand-made to machine-made products a new era of human experience began where increased productivity created a much higher standard of living than had ever been known in the pre-industrial world.

The start of the American Industrial Revolution is often attributed to Samuel Slater who opened the first industrial mill in the United States in 1790 with a design that borrowed heavily from a British model. Slater’s pirated technology greatly increased the speed with which cotton thread could be spun into yarn. While he introduced a vital new technology to the United States, the economic takeoff of the Industrial Revolution required several other elements before it would transform American life.

Another key to the rapidly changing economy of the early Industrial Revolution were new organizational strategies to increase productivity. This had begun with the “outwork system” whereby small parts of a larger production process were carried out in numerous individual homes. This organizational reform was especially important for shoe and boot making. However, the chief organizational breakthrough of the Industrial Revolution was the “factory system” where work was performed on a large scale in a single centralized location. Among the early innovators of this approach were a group of businessmen known as the Boston Associates who recruited thousands of New England farm girls to operate the machines in their new factories.

The most famous of their tightly controlled mill towns was Lowell, Massachusetts, which opened in 1823. The use of female factory workers brought advantages to both employer and employee. The Boston Associates preferred female labor because they paid the young girls less than men. These female workers, often called “Lowell girls,” benefited by experiencing a new kind of independence outside the traditional male-dominated family farm.

The rise of wage labor at the heart of the Industrial Revolution also exploited working people in new ways. The first strike among textile workers protesting wage and factory conditions occurred in 1824 and even the model mills of Lowell faced large strikes in the 1830s.

Dramatically increased production, like that in the New England’s textile mills, were key parts of the Industrial Revolution, but required at least two more elements for widespread impact. First, an expanded system of credit was necessary to help entrepreneurs secure the capital needed for large-scale and risky new ventures. Second, an improved transportation system was crucial for raw materials to reach the factories and manufactured goods to reach consumers. State governments played a key role encouraging both new banking institutions and a vastly increased transportation network. This latter development is often termed the market revolution because of the central importance of creating more efficient ways to transport people, raw materials, and finished goods.

Alexander Hamilton’s Bank of the United States received a special national charter from the U.S. Congress in 1791. It enjoyed great success, which led to the opening of branch offices in eight major cities by 1805. Although economically successful, a government-chartered national bank remained politically controversial. As a result, President Madison did not submit the bank’s charter for renewal in 1811. The key legal and governmental support for economic development in the early 19th century ultimately came at the state, rather than the national, level. When the national bank closed, state governments responded by creating over 200 state-chartered banks within five years. Indeed, this rapid expansion of credit and the banks’ often unregulated activities helped to exacerbate an economic collapse in 1819 that resulted in a six-year depression. The dynamism of a capitalist economy creates rapid expansion that also comes with high risks that include regular periods of sharp economic downturns.

The use of a state charter to provide special benefits for a private corporation was a crucial and controversial innovation in republican America. The idea of granting special privileges to certain individuals seemed to contradict the republican ideal of equality before the law. Even more than through rapidly expanded banking institutions, state support for internal transportation improvements lay at the heart of the nation’s new political economy. Road, bridge, and especially canal building was an expensive venture, but most state politicians supported using government-granted legal privileges and funds to help create the infrastructure that would stimulate economic development.

The most famous state-led creation of the Market Revolution was undoubtedly New York’s Erie Canal. Begun in 1817, the 364-mile man-made waterway flowed between Albany on the Hudson River and Buffalo on Lake Erie. The canal connected the eastern seaboard and the Old Northwest. The great success of the Erie Canal set off a canal frenzy that, along with the development of the steamboat, created a new and complete national water transportation network by 1840.

Source: Economic Growth and the Early Industrial Revolution. U.S. History.org. Retrieved from http://www.ushistory.org/us/22a.asp

Summary

In the early nineteenth century, the industrial revolution transformed the economy of the United States. The industrial revolution first began in Great Britain in the eighteenth century. By the early nineteenth century, the industrial revolution began to impact New England. Samuel Slater established the first successful cotton mill in Providence, Rhode Island. The Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 made it more difficult for American merchants to import manufactured goods from Europe. As a result, the Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812 stimulated the expansion of industry in the United States. The industrial revolution greatly increased the production of goods in the United States. With the rise of industry, labor became increasingly specialized, as the tasks of production were broken down into simple steps. The most prominent industry in America was the production of cotton and woollen cloth.