In the early years of the nineteenth century, Americans’ endless commercial ambition—what one Baltimore paper in 1815 called an “almost universal ambition to get forward”—remade the nation. Between the Revolution and the Civil War, an old subsistence world died and a new more-commercial nation was born. Americans integrated the technologies of the Industrial Revolution into a new commercial economy. Steam power, the technology that moved steamboats and railroads, fueled the rise of American industry by powering mills and sparking new national transportation networks. A “market revolution” remade the nation.

The revolution reverberated across the country. More and more farmers grew crops for profit, not self-sufficiency. Vast factories and cities arose in the North. Enormous fortunes materialized. A new middle class ballooned. And as more men and women worked in the cash economy, they were freed from the bound dependence of servitude. But there were costs to this revolution. As northern textile factories boomed, the demand for southern cotton swelled, and American slavery accelerated. Northern subsistence farmers became laborers bound to the whims of markets and bosses.

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The Market Revolution

The market revolution sparked explosive economic growth and new personal wealth, but it also created a growing lower class of property-less workers and a series of devastating depressions, called “panics.” Many Americans labored for low wages and became trapped in endless cycles of poverty. Some workers, often immigrant women, worked thirteen hours a day, six days a week. Others labored in slavery. Massive northern textile mills turned southern cotton into cheap cloth. And although northern states washed their hands of slavery, their factories fueled the demand for slave-grown southern cotton and their banks provided the financing that ensured the profitability and continued existence of the American slave system. And so, as the economy advanced, the market revolution wrenched the United States in new directions as it became a nation of free labor and slavery, of wealth and inequality, and of endless promise and untold perils.

The growth of the American economy reshaped American life in the decades before the Civil War. Americans increasingly produced goods for sale, not for consumption. Improved transportation enabled a larger exchange network. Labor-saving technology improved efficiency and enabled the separation of the public and domestic spheres. The market revolution fulfilled the revolutionary generation’s expectations of progress but introduced troubling new trends. Class conflict, child labor, accelerated immigration, and the expansion of slavery followed.

American commerce had proceeded haltingly during the eighteenth century. American farmers increasingly exported foodstuffs to Europe as the French Revolutionary Wars devastated the continent between 1793 and 1815. America’s exports rose in value from $20.2 million in 1790 to $108.3 million by 1807. But while exports rose, exorbitant internal transportation costs hindered substantial economic development within the United States. But in the wake of the War of 1812, Americans rushed to build a new national infrastructure, new networks of roads, canals, and railroads. In his 1815 annual message to Congress, President James Madison stressed “the great importance of establishing throughout our country the roads and canals which can best be executed under national authority.” State governments continued to sponsor the greatest improvements in American transportation, but the federal government’s annual expenditures on internal improvements climbed to a yearly average of $1,323,000 by Andrew Jackson’s presidency.

State legislatures meanwhile pumped capital into the economy by chartering banks. The number of state-chartered banks skyrocketed from 1 in 1783 to 1,371 in 1860. European capital also helped to build American infrastructure. By 1844, one British traveler declared that “the prosperity of America, her railroads, canals, steam navigation, and banks, are the fruit of English capital.”

The so-called “Transportation Revolution” opened the vast lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1810, before the rapid explosion of American infrastructure, Margaret Dwight left New Haven, Connecticut, in a wagon headed for Ohio Territory. Her trip was less than 500 miles but took six full weeks to complete. The journey was a terrible ordeal, she said. Nineteen years later, in 1829, English traveler Frances Trollope made the reverse journey across the Allegheny Mountains from Cincinnati to the east coast. At Wheeling, Virginia, her coach encountered the National Road, the first federally funded interstate infrastructure project. The road was smooth and her journey across the Alleghenies was a scenic delight.

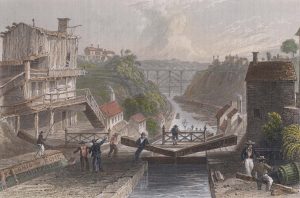

New York State completed the Erie Canal in 1825. The 350 mile-long manmade waterway linked the Great Lakes with the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean. Soon crops grown in the Great Lakes region were carried by water to eastern cities, and goods from emerging eastern factories made the reverse journey to midwestern farmers. The success of New York’s “artificial river” launched a canal-building boom. By 1840 Ohio created two navigable, all-water links from Lake Erie to the Ohio River.

Robert Fulton established the first commercial steam boat service up and down the Hudson River in New York in 1807. Soon thereafter steamboats filled the waters of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. Downstream-only routes became watery two-way highways. By 1830, more than 200 steamboats moved up and down western rivers.

The United States’ first long-distance rail line launched from Maryland in 1827. Baltimore’s city government and the state government of Maryland provided half the start-up funds for the new Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Rail Road Company. The B&O’s founders imagined the line as a means to funnel the agricultural products of the trans-Appalachian West to an outlet on the Chesapeake Bay. Similar motivations led citizens in Philadelphia, Boston, New York City, and Charleston, South Carolina to launch their own rail lines. State and local governments provided the means for the bulk of this initial wave of railroad construction. Government supports continued throughout the century, but decades later the public origins of railroads were all but forgotten, and the railroad corporation became the most visible embodiment of corporate capitalism.

By 1860 Americans laid more than 30,000 miles of railroads. The ensuing web of rail, roads, and canals meant that few farmers in the Northeast or Midwest had trouble getting goods to urban markets. Railroad development was slower in the South, but there a combination of rail lines and navigable rivers meant that few cotton planters struggled to transport their products to textile mills in the Northeast and in England.

Such internal improvements not only spread goods, they spread information. The “transportation revolution” was followed by a “communications revolution.” The telegraph redefined the limits of human communication. By 1843 Samuel Morse persuaded Congress to fund a forty-mile telegraph line stretching from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore. Within a few short years, during the Mexican-American War, telegraph lines carried news of battlefield events to eastern newspapers within days.

The consequences of the transportation and communication revolutions reshaped the lives of Americans. Farmers who previously produced crops mostly for their own family now turned to the market. They earned cash for what they had previously consumed; they purchased the goods they had previously made or went without. Market-based farmers soon accessed credit through eastern banks, which provided them with the opportunity to expand their enterprise but left also them prone before the risk of catastrophic failure wrought by distant market forces. In the Northeast and Midwest, where farm labor was ever in short supply, ambitious farmers invested in new technologies that promised to increase the productivity of the limited labor supply. The years between 1815 and 1850 witnessed an explosion of patents on agricultural technologies. The most famous of these, perhaps, was Cyrus McCormick’s horse-drawn mechanical reaper, which partially mechanized wheat harvesting, and John Deere’s steel-bladed plough, which more easily allowed for the conversion of unbroken ground into fertile farmland.

The cash economy eclipsed the old, local, informal systems of barter and trade. Income became the measure of economic worth. Productivity and efficiencies paled before the measure of income. Cash facilitated new impersonal economic relationships and formalized new means of production. Young workers might simply earn wages, for instance, rather than receiving room and board and training as part of apprenticeships. Moreover, a new form of economic organization appeared: the business corporation.

States offered the privileges of incorporation to protect the fortunes and liabilities of entrepreneurs who invested in early industrial endeavors. A corporate charter allowed investors and directors to avoid personal liability for company debts. The legal status of incorporation had been designed to confer privileges to organizations embarking upon expensive projects explicitly designed for the public good, such as universities, municipalities, and major public works projects. The business corporation was something new. Many Americans distrusted these new, impersonal business organizations whose officers lacked personal responsibility while nevertheless carrying legal rights. Many wanted limits. Thomas Jefferson himself wrote in 1816 that “I hope we shall crush in its birth the aristocracy of our monied corporations which dare already to challenge our government to a trial of strength, and bid defiance to the laws of our country.” But in Dartmouth v. Woodward (1819) the Supreme Court upheld the rights of private corporations when it denied the government of New Hampshire’s attempt to reorganize Dartmouth College on behalf of the common good. Still, suspicions remained. A group of journeymen cordwainers in New Jersey publically declared in 1835 that they “entirely disapprov[ed] of the incorporation of Companies, for carrying on manual mechanical business, inasmuch as we believe their tendency is to eventuate and produce monopolies, thereby crippling the energies of individual enterprise.”

Source: The American Yawp. A Free and Online, Collaboratively Built American History Textbook, 2017-2018 Edition.

The Market Revolution

By the 1830s, the United States had developed a thriving industrial and commercial sector in the Northeast. Farmers embraced regional and distant markets as the primary destination for their products. Artisans witnessed the methodical division of the labor process in factories. Wage labor became an increasingly common experience. These industrial and market revolutions, combined with advances in transportation, transformed the economic and social landscape. Americans could now quickly produce larger amounts of goods for a nationwide, and sometimes an international, market and rely less on foreign imports than in colonial times.

Northern industrialization expanded rapidly following the War of 1812. Industrialized manufacturing began in New England, where wealthy merchants built water-powered textile mills (and mill towns to support them) along the rivers of the Northeast. These mills introduced new modes of production centralized within the confines of the mill itself. As never before, production relied on mechanized sources with water power, and later steam, to provide the force necessary to drive machines. In addition to the mechanization and centralization of work in the mills, specialized, repetitive tasks assigned to wage laborers replaced earlier modes of handicraft production done by artisans at home. The operations of these mills irrevocably changed the nature of work by deskilling tasks, breaking down the process of production to its most basic, elemental parts. In return for their labor, the workers, who at first were young women from rural New England farming families, received wages. From its origin in New England, manufacturing soon spread to other regions of the United States.

Entrepreneurs and Inventors

In the 1800s, a frenzy of entrepreneurship and invention yielded many new products and machines. The republic seemed to be a laboratory of innovation, and technological advances appeared unlimited.

One influential new technology of the early 1800s was the steamship engine, invented by Robert Fulton in 1807. Fulton’s first steamship, the Clermont, used paddle wheels to travel the 150 miles from New York City to Albany in a record time of only thirty-two hours (Figure 9.11). Soon, a fleet of steamboats was traversing the Hudson River and New York Harbor, later expanding to travel every major American river including the mighty Mississippi. By the 1830s there were over one thousand of these vessels, radically changing water transportation by ending its dependence on the wind. Steamboats could travel faster and more cheaply than sailing vessels or keelboats, which floated downriver and had to be poled or towed upriver on the return voyage. Steamboats also arrived with much greater dependability. The steamboat facilitated the rapid economic development of the massive Mississippi River Valley and the settlement of the West.

Samuel Morse added the telegraph to the list of American innovations introduced in the years before the Civil War. Born in Massachusetts in 1791, Morse first gained renown as a painter before turning his attention to the development of a method of rapid communication in the 1830s. In 1838, he gave the first public demonstration of his method of conveying electric pulses over a wire, using the basis of what became known as Morse code. In 1843, Congress agreed to help fund the new technology by allocating $30,000 for a telegraph line to connect Washington, DC, and Baltimore along the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In 1844, Morse sent the first telegraph message on the new link. Improved communication systems fostered the development of business, economics, and politics by allowing for dissemination of news at a speed previously unknown.

On the Move: The Transportation Revolution

Americans in the early 1800s were a people on the move, as thousands left the eastern coastal states for opportunities in the West. Unlike their predecessors, who travelled by foot or wagon train, these settlers had new transport options. Their trek was made possible by the construction of roads, canals, and railroads, projects that required the funding of the federal government and the states.

New technologies, like the steamship and railroad lines, had brought about what historians call the transportation revolution. States competed for the honor of having the most advanced transport systems.

People celebrated the transformation of the wilderness into an orderly world of improvement demonstrating the steady march of progress and the greatness of the republic. In 1817, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina looked to a future of rapid internal improvements, declaring, “Let us . . . bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals.” Americans agreed that internal transportation routes would promote progress. By the eve of the Civil War, the United States had moved beyond roads and canals to a well-established and extensive system of railroads.

Roads and Canals

One key part of the transportation revolution was the widespread building of roads and turnpikes. In 1811, construction began on the Cumberland Road, a national highway that provided thousands with a route from Maryland to Illinois. The federal government funded this important artery to the West, beginning the creation of a transportation infrastructure for the benefit of settlers and farmers. Other entities built turnpikes, which (as today) charged fees for use. New York State, for instance, chartered turnpike companies that dramatically increased the miles of state roads from one thousand in 1810 to four thousand by 1820. New York led the way in building turnpikes.

Canal mania swept the United States in the first half of the nineteenth century. Promoters knew these artificial rivers could save travellers immense amounts of time and money. Even short waterways, such as the two-and-a-half-mile canal going around the rapids of the Ohio River near Louisville, Kentucky, proved a huge leap forward, in this case by opening a water route from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. The preeminent example was the Erie Canal (Figure 9.13), which linked the Hudson River, and thus New York City and the Atlantic seaboard, to the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River Valley.

With its central location, large harbor, and access to the hinterland via the Hudson River, New York City already commanded the lion’s share of commerce. Still, the city’s merchants worried about losing ground to their competitors in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Their search for commercial advantage led to the dream of creating a water highway connecting the city’s Hudson River to Lake Erie and markets in the West. The result was the Erie Canal. Chartered in 1817 by the state of New York, the canal took seven years to complete. When it opened in 1825, it dramatically decreased the cost of shipping while reducing the time to travel to the West. Soon $15 million worth of goods (more than $200 million in today’s money) was being transported on the 363-mile waterway every year.

As with highway projects such as the Cumberland Road, many canals were federally sponsored, especially during the presidency of John Quincy Adams in the late 1820s. Adams, along with Secretary of State Henry Clay, championed what was known as the American System, part of which included plans for a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and develop markets for agriculture as well as to advance settlement in the West.

Railroads

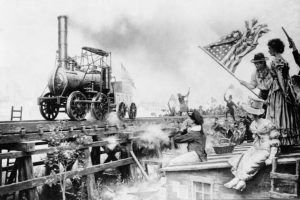

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn locomotives. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

Americans on the Move

The expansion of roads, canals, and railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. Together with the hundreds of steamboats that plied American rivers, these advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the market revolution would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution. Traveling circuses, menageries, peddlers, and itinerant painters could now more easily make their way into rural districts, and people in search of work found cities and mill towns within their reach.

Source: Corbett, P.S., Janssen V., Lund, J., Pfannestiel, T., Vickery, P., & Waskiewicz, S. U.S. History. OpenStax. 30 December 2014.

Summary

The economy of the United States underwent a major transformation in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. The United States emerged as a leading industrial power during this period. Advancements in transportation and communications technologies were crucial to the economic development of the United States during this period. The development of canals, steamships, and railways contributed to rapid improvements in transportation. In 1825, the Erie Canal was completed, linking the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. Meanwhile, Robert Fulton developed the steamship that dramatically improved transportation. The federal government invested significant resources in the development of railways during this period. Communication across great distances became possible with the development of the telegraph and Morse Code by Samuel Morse. Tragically, many people were harmed by the economic development of the U.S. Many industrial laborers worked long hours in terrible factory conditions for little pay. Meanwhile, the expansion of the textile industry in the North created a demand for Cotton that was produced by slave labor in the American South.