There was a religious and cultural component to the party divide that emerged in both the Second and Third Party Systems.

In the Second Party system, the two dominant parties were the Whigs and Democrats. The Whig Party appealed largely to evangelical Protestants. The Whigs advanced the idea that society could be perfected through moral reform. The Whig Party promoted an ambitious agenda to prohibit activities that they regarded as immoral such as the production and sale of alcohol, gambling, and prostitution. In contrast, the Democratic Party adopted a libertarian position on moral issues. The Democratic Party opposed the temperance movement and movements to prohibit gambling, prostitution, etc. The Democratic Party won support from Irish Catholic immigrants residing in urban areas.

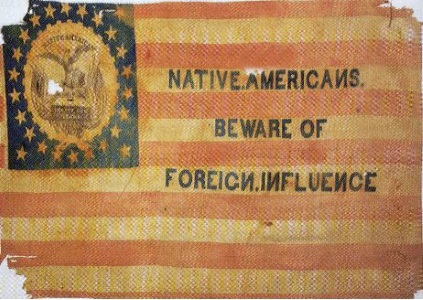

The religious divisions present in the Second Party System re-emerged in the Third Party System. With the collapse of the Whig Party, two new political parties emerged to appeal to evangelical Protestants. The American or Know Nothing Party embraced an anti-immigrant platform, emphasizing hostility towards Roman Catholicism. The Republican Party embraced the moral reform movement that had once been associated with the Whigs.

Religion and Politics

The political cosmos of the ante-bellum period was profoundly shaped by popular religious culture and especially by its most powerful element, the forces of evangelical Protestantism. The evangelical religion that blossomed during the so-called Second Great Awakening exerted a powerful political influence, encouraging civic responsibility and popular participation in politics, shaping party loyalties, platforms, and agendas, and providing the coin of politics.

Evangelical religion shaped American political culture, not only in the era of mature party competition between Whigs and Democrats—but in the subsequent decade, the years of the emergent “third party system,” when the continuing but southern-oriented Democratic party faced an insurgent, crusading Republican party. Republican publicists, sensitive to evangelicals’ influence, proved as alert as any of their predecessors to the electoral benefits of addressing the fears and aspirations of that powerful constituency.

Over the first thirty years of the nineteenth century—the era of the Second Great Awakening—American evangelical Protestantism enjoyed a period of dramatic numerical growth. By 1850, the largest Protestant denominational families—Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists—claimed a communicating membership of nearly three million and a total “population” (which embraced regular “hearers” as well as members) three times as large. At mid-century one out of every three Americans came within the orbit of the major evangelical churches.

The climactic years of the Second Great Awakening coincided with the emergence of a recognizably modern mass democratic political system. Evangelicals sought to come to terms with the new order and establish the proper limits to their civic duty. The majority of evangelicals drew on a Calvinist understanding of politics as a means of introducing God’s kingdom and perceived the state as a moral being. As postmillennialists who believed that Christ’s return would follow the inauguration of a glorious millennium brought about by burgeoning human efforts, these evangelicals stressed the public responsibilities of Christians. They urged them to vote to secure the election of good men and to lobby for laws appropriate to a Christian republic. They were anxious about many of the political innovations in Jacksonian America, particularly the threat to republicanism represented by professional politicians, tight party discipline, the subordination of principle to spoils of office, and the tumult of mass elections. But whatever their anxieties, “Calvinist” evangelicals were determined to purify political life.

By mid-century, indeed, most male evangelical Protestants were deeply involved in politics. They attended rallies, avidly read political papers, and canvassed for particular candidates. Ministers were often energetic partisans.

The new political arrangements were themselves deeply influenced by the revivalist culture of the Second Great Awakening—by evangelicals’ language, modes of operation, religious sensibilities, and moral imperatives. The party strategists recognized that religious passions might provide a basis for political loyalty. They invited ministers to offer prayers at party conventions; they ran political gatherings along the lines of camp and protracted meetings; their songs often echoed Protestant hymnody; they played “recognition” politics by running candidates known to be attached to those denominations whose members’ votes were pivotal; and they replicated the evangelicals’ mind-set of a world sharply divided between irreconcilable forces.

Whigs made a bid for the support of evangelicals who, while committed to the classic Protestant virtues of self-control and self-discipline, also welcomed an interventionist government that would regulate social behavior and maintain moral standards in public life. The party’s publicists presented it as the friend of educational provision, temperance, and the humane treatment of those who stood in a dependent relationship to the state. They commonly portrayed their opponents as atheists and religious perverts, the allies of Mormons, freethinkers, and Roman Catholics. In successive elections in the 1840s, Whigs made much of their credentials as “the Christian party.”

In the Presidential election of 1844, the Whigs chose as Clay’s running mate the most illustrious lay evangelical in the country, Theodore J. Frelinghuysen, a man more at home on the religious platform than the political hustings. At a time when many evangelicals were particularly fearful of what they saw as a Catholic threat to Bible reading in common schools (fears that provoked bloody riots in Philadelphia in the summer of 1844), who could better assert the Whigs’ claims to be the “Protestant party” than the stalwart of the American Bible Society, Frelinghuysen himself?

Religious loyalties and antagonisms were a major, and sometimes the main, determinant of party attachment. Interdenominational conflicts and differing views on the proper role of government in sustaining a Christian republic helped determine party affiliation. Certain denominations showed much stronger support for one party over another. During the second party system, New School Calvinists were strongly Whig; the Democrats’ particular strength lay among Catholics. Many Methodists, Baptists, and Old School Calvinists rallied to Whiggery.

Lincoln’s Republican Party absorbed from Whiggery many lessons about marshalling the energy of religious enthusiasts. Republican managers knew the advantages of presenting candidates and platforms as embodiments of Christian virtue. The new Republican Party also absorbed many lessons from the successes of the American or Know Nothing Party. The American or Know-Nothing Party was committed to ending the immigration of Irish Catholics to the United States.

Republicans presented Lincoln as a candidate rooted in sound Protestant orthodoxy. Lincoln was extolled in the press as one who had “always held up the doctrines of the Bible, and the truths and examples of the Christian religion, as the foundation of all good.” He enjoyed the confidence of the religious community and was a staunch believer in Sabbath schools. Party publicists also celebrated Lincoln as a man of blameless behavior: he never used profane language; he did not gamble; and he avoided all intoxicating liquor, even wine.

Lincoln’s promoters projected him as a leader destined to deliver the nation “from the rule of a Godless … Administration.” Republicans, as had the Whigs before them, castigated Democrats for their moral shortcomings and particularly for their subordination to Catholic influence. Among the Republican editors who upheld his Christian integrity were those who also deliberately branded Stephen Douglas with the mark of the Beast. Republican editors branded Douglas as a moral leper and a drunkard, who “trifle[d] with the law of Sinai as freely as a hoary-headed gambler would … throw dice on a New Orleans sugar barrel for ‘pig tail’ tobacco!” Having abandoned his family’s Calvinism in favor of close ties with the Catholic hierarchy, he had visited Rome and (it was claimed) submitted to the Pope, receiving absolution and “the right hand of fellowship.” Republican editors claimed that his marriage to a Catholic woman and the support he secured from Illinois Romanist voters in 1858 pointed to a “secret understanding between him and the leading men of … [the Catholic Church] in America, whereby he is to have their votes … for a consideration.” The “troop of wild Irish” would surely support Douglas again in 1860 and, with their man in the White House, make Archbishop John Hughes “the keeper of the conscience of the King.” But vote for Lincoln, insisted the Cincinnati Rail Splitter, “and this Government [would] still remain in Protestant control.”

Republicans’ anti-Catholicism played upon a number of related but distinct fears: the theological-ecclesiastical anxieties of staunch Protestants who regarded Rome as the antichrist and the murderer of religious liberties; the social phobia of nativists who equated Catholicism with Irish immigrants; and the political antipathy of antislavery reformers who believed the Roman Church to be minted from the same metal as a slave Power equally hostile to republican freedoms. Republicans’ anti-Catholic posture had been well established through the late 1850s, and many of their speakers and candidates in 1860 were known nativists and anti-Romanists.

Closely related to the Republicans’ use of anti-Romanist sentiment was their stress on corruption in the national administration. The party took over much of the language of purification that Whigs had used in an earlier era. In 1860 the Democrats, after forming three of the last four national administrations, were again vulnerable to the charge of carrying the nation to the brink of moral crisis. The Republicans’ promised to encourage “a revival of moral honesty and integrity, in all departments of life.”

If Republicans in 1860 promoted themselves and their candidate as the embodiment of uncorrupted Protestantism, the question arises: how far did the members of northern evangelical denominations cleave to that party? Did Republicans, as “the Christian party,” manage to attract the bulk of evangelical churchgoers? There is little doubt that Republicans inherited from Whiggery the majority of Congregationalist and New School Presbyterian voters and enjoyed the support of the smaller, earnestly antislavery denominations, including Quakers, Freewill Baptists, Wesleyan Methodists, and Free Presbyterians; they also won over large numbers of Methodists and Baptists.

Source: Carwardine, Richard, J. (1997). “Lincoln, evangelical religion, and American political culture in -the era of the Civil War.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association 18(1): 27-55.

Religion and Politics – video

Foner, E. Politics, Whiteness, Religion: The Civil War and Reconstruction. (2014, October 29). [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbFz8Codg5k

Summary

The Second Party System and Third Party System were both deeply influenced by religion. In the Second Party system, the Whig Party appealed largely to evangelical Protestants and promoted a variety of moral reform movements such as temperance. In contrast, the Democratic Party appealed to Roman Catholic immigrants, especially Irish Catholic immigrants. The Democratic Party promoted moral libertarianism. In the Third Party System, the Republican Party appealed largely to evangelical Protestants. The Republican Party promoted moral reform movements such as abolitionism. The Democratic Party continued to appeal to the expanding Irish Catholic immigrant population. The American Party or Know Nothing Party emerged as a significant third party in this period. The American Party or Know Nothing Party called for an end to Irish Catholic immigration to the United States.